2 CHOICE OF ROOF STRUCTURE

For a roof to function satisfactorily, several legal and functional requirements must be met. The Building Regulations contain very few provisions specifically for roof structure performance, including thermal transmittance (U-value), roof drainage (roof pitch), fire safety, acoustic insulation, and protection against falling hazards. In addition, roofs are subject to the general provisions for structures in the Building Regulations (BR18, § 340–341), stipulating that satisfactory conditions must be achieved in terms of performance and durability and that the materials used must be durable and appropriate for the intended purpose.

The most important functions of a roof structure are as follows. It must:

- be watertight/act as a rain shield (prevent rainfall intrusion),

- provide drainage,

- be impermeable to vapour from the inside (diffusion and convection),

- prevent moisture accumulation (moisture which migrates into the structure must be able to escape),

- be airtight (for energy consumption and comfort),

- reduce heat loss (to be thermally insulating),

- be harmless (fire, chemicals in the materials, etc.),

- be sufficiently stable and robust to handle expected usage loads (no collapse or damage resulting from impacts or people falling),

- reduce outside noise to acceptable levels,

- be environmentally acceptable (have minimal environmental impact),

- help prevent break-ins, and

- be durable (have a long lifespan).

Certain roofs may have supplementary functions depending on specific requirements. For example, the roof should be capable of supporting maintenance people and servicing (e.g., of ventilation systems). There are separate requirements for roof terraces, roof gardens, and parking decks.

Individual roofing materials may also have unique functions, placing demands on the properties of the given material, for example, the vapour-impermeability or -permeability of roofing underlayment materials relative to the specific structural assemblies.

By combining the function of the roof with the conditions which the roof is exposed to, a set of requirements detailing the performance properties required for a roof can be formulated. These properties will, for example, depend on:

- the function of the building (its use) (e.g., whether it is a dry storage hall or a swimming pool),

- the shape intended for the building (e.g., for very large buildings, the options for roof shape will often be limited),

- the specific climate conditions the building will be exposed to, including both outdoor and indoor climate (moisture load classes) (cf. Section 1.2, Vented and Unvented Assemblies).

There will usually be several different options when deciding on a roof structure, but it will always be necessary to select one that will meet the functions outlined above. Other factors and needs should also be considered, including environmental requirements, local development plans, and aesthetic considerations.

It is a given that it must be possible to build the roof, and it should preferably be simple and safe to perform the necessary work operations on the building site. Due consideration should therefore be given to both contractors and the overall quality of the roof structure which will benefit in quality if risks (such as the risk of incorrect installation) are reduced.

Very often, economy will also be a decisive factor in the design of a roof. It is important to focus not only on keeping initial costs low, but also to consider how costs will accumulate over the lifespan, operations, and maintenance.

Ultimately, the choice of a specific roof type should always be made by carefully considering the advantages and disadvantages of the feasible options.

2.1 Water and Moisture Tightness

Roofs may be impacted by moisture in various forms, including:

- precipitation (driving rain and drifting snow) which may penetrate the structure from the outside,

- moisture in the outside air,

- moisture in the indoor air migrating into the assembly by diffusion through the materials, or by convection (airflow) via leakages,

- moisture from the building process (i.e., water introduced during or remaining from the construction phase),

- condensation of vapour in the outer parts of the assembly due to surface radiant emissions to the atmosphere, which reduce surface temperatures to below dew point.

Wind on the exterior surface of a roof can considerably increase moisture impact. The wind can cause precipitation to behave like driving rain or drifting snow, both of which can be directed upwards. Therefore, in adverse situations, both can penetrate structures where watertightness is partly achieved by overlapping joints, such as in roof tiles or parapet coping.

Wind can also generate both positive and negative pressure in roofs, although in roofs with a shallow pitch there will almost always be negative pressure across the whole of the exposed roof surface. In an unsuitable flat roof assembly, negative pressure may propagate into the vent space, thereby intensifying the convection of indoor air into the roof unless a completely airtight layer has been established in the assembly.

The risk of moisture absorption due to convection is greater in roofs than in exterior walls because the thermal uplift caused by the indoor air will always cause slight, but constant, positive pressure below the ceiling or roof. During winter, the positive pressure will result in indoor air migrating into the roof structure. Even when a good quality vapour barrier has been correctly fitted, small amounts of vapour will migrate into the loft space. Vapor will similarly be able to migrate through air leakages, such as those around trapdoors and penetrations.

2.1.1 General Protective Measures Against Moisture Absorption

Rain and melting snow must be prevented from entering roof assemblies, which must be watertight. However, in roof assemblies with roofing underlayment, small amounts of precipitation are able to migrate through the primary roof covering. Water must be drained away from the roof or roofing underlayment as quickly as possible, mitigating the risk of damage to underlying structures resulting from moisture absorption.

Moisture absorption in roof assemblies from humid indoor air must be prevented. Hence, roof assemblies usually include vapour barriers to prevent humid indoor air from entering the roof structure through diffusion or convection (see the following Section 2.1.2, Vapour Barriers in Roofs). If, rather than vapour barriers, alternative solutions are preferred, this must be documented, for example with calculations.

Care must be taken to avoid allowing moisture from the building process to migrate into the roof structure. Accordingly, the work should be carried out in dry weather and work in progress should be covered up at the end of each working day. Roofing components supplied with pre-installed roof covering must have their joints taped (i.e., a strip of roofing membrane must be fitted across the joints) immediately after installation. Alternatively, the whole building site must be covered, total covering being the most effective method (see Section 4, Composite Roofing Slabs).

2.1.2 Vapour Barriers in Roofs

Vapour barriers are normally supplied as roll material (e.g., polyethylene (PE) foil). Other types of material may also be used, such as sheet materials. If sheet materials are used, detailed installation instructions should be available, including guidelines on how the sheet materials should be joined and how penetrations should be designed because most guidelines in use concern roll materials.

Applicable Standards

Vapour barriers are subject to the following product standards:

- Vapour barriers made of plastic or rubber: DS/EN 13984, Flexible sheets for waterproofing – Plastic and rubber vapour control layers – Definitions and characteristics (Danish Standards, 2013b)

- Bituminous vapour barriers: DS/EN 13970, Flexible sheets for waterproofing – Bitumen water vapour control layers – Definitions and characteristics (Danish Standards, 2005a).

Vapour barriers made of sheet materials, must satisfy the provisions of the standards for the relevant products and their diffusion resistance must be documented.

Issues concerning vapour barriers in connection with roof renovation are outlined in Section 8.2.3, Vapour Barriers and Roof Renovation.

Properties Required of Vapour Barriers

A vapour barrier must:

- be made of a vapour-impermeable (vapour tight) material, which prevents water vapour transmission by diffusion (i.e., a material with a high diffusion resistance factor (Z-value)),

- be designed as an airtight installation because moisture penetrating the roof structure through convection (airflow) cannot normally be removed fast enough by ventilation or diffusion,

- be made of appropriate and robust material capable of being handled on a building site, and

- have a long lifespan when exposed to the stress loads imposed by the completed roof structure.

For renovations, separate rules apply (see Section 8.2.3, Vapour Barriers and Roof Renovation).

Please note that plaster ceilings can be regarded as airtight if they are intact (i.e., free of cracks or holes) but they are not vapour-impermeable and should be fitted with a vapour barrier.

Properties of Vapour Barriers

Vapour barriers should normally have a minimum Z-value of 50 GPa s m2/kg. The requisite Z-value can be determined by testing according to DS/EN 1931, Flexible Sheets for Waterproofing – Bitumen, Plastic, and Rubber Sheets for Roof Waterproofing – Determination of Water Vapour Transmission Properties (Danish Standards, 2000a), or to DS/EN/ISO 12572, Hygrothermal Performance of Building Materials and Products – Determination of Water Vapour Transmission Properties – Cup Method (Danish Standards, 2016a).

Vapour barriers must, furthermore, have excellent dimensional stability, strength, and elongation at fracture capacity and should be capable of tolerating reasonable levels of impact such as bumps and knocks without being damaged.

Its lifespan should be documented (e.g., assessed using accelerated ageing tests). Similarly, documentation should include ancillary materials such as butyl tape sealant, adhesive tape, foil adhesive, and caulking compound.

We recommend that ’systems solutions’ be used as much as possible, for example, where the vapour barrier and ancillary materials such as tape, foil-adhesive, sleeves, and caulking compound are supplied by the same source. This is the best way of ensuring that the materials used will work in combination and achieve optimal results.

Diffusion Resistance

As mentioned above, vapour barrier products usually have a high diffusion resistance (i.e., a minimum Z-value of 50 GPa s m2/kg). This means that materials like PE foil, PVC foil, or roofing membranes can be used as vapour barriers.

Systems solutions using materials with a diffusion resistance of less than 50 GPa s m2/kg are available on the market. If these systems solutions are used, care must be taken to construct the assembly in such a way as to avoid vapour damage from the interior of the building, for example, by using high-performance vapour-permeable materials further within the structure, beyond the initial vapor barrier.

Moisture-adaptive vapour barriers are vapour barriers with diffusion properties relative to the ambient moisture content. At low relative humidity levels, moisture-adaptive vapour barriers are vapour-impermeable (and function as vapour barriers) while at high relative humidity (RH) levels they are vapour-permeable. At high RH levels, therefore, the materials allow moisture to migrate (i.e., they do not function as vapour barriers at high RH levels). Moisture-adaptive vapour barriers require special conditions to function correctly, as they are dependent on the roof being heated by solar radiation during the summer. Their use is therefore typically limited to flat roofs (with slopes of less than 10 °) and mono-pitch roofs facing a south-eastern to south-south-western direction. The roof covering must be dark (e.g., bituminous felt, dark roofing foil, or zinc). Special care should be taken when applying moisture-adaptive vapour barriers in moisture load class 3. It is not advisable to use moisture-adaptive vapour barriers in moisture-load classes 4 and 5.

Buildings graded according to moisture load classes relative to their usage are shown in Table 1.

Airtightness

Convection (airflow) of moist indoor air via air leakage paths is usually the most common cause of vapour absorption in roof structures. Since thermal uplift leads to a greater risk of convection in roof structures than in exterior walls, it is particularly important that the vapour barrier is airtight. This requires that all details to be planned carefully and practically with appropriate ancillary materials including adhesive tape, foil adhesive, etc.

The 2018 Danish Building Regulations contain specific provisions for airtightness. These provisions stipulate that the flow rate through air leakage paths in the building envelope in new buildings heated to 15 °C or more, must not exceed 1.0 l/s per m² heated floor space at a pressure difference of 50 Pa (BR18, § 263). For the optional low-energy class, the requirements are 0.7 l/s per m2 of heated floor space (BR18, § 481).

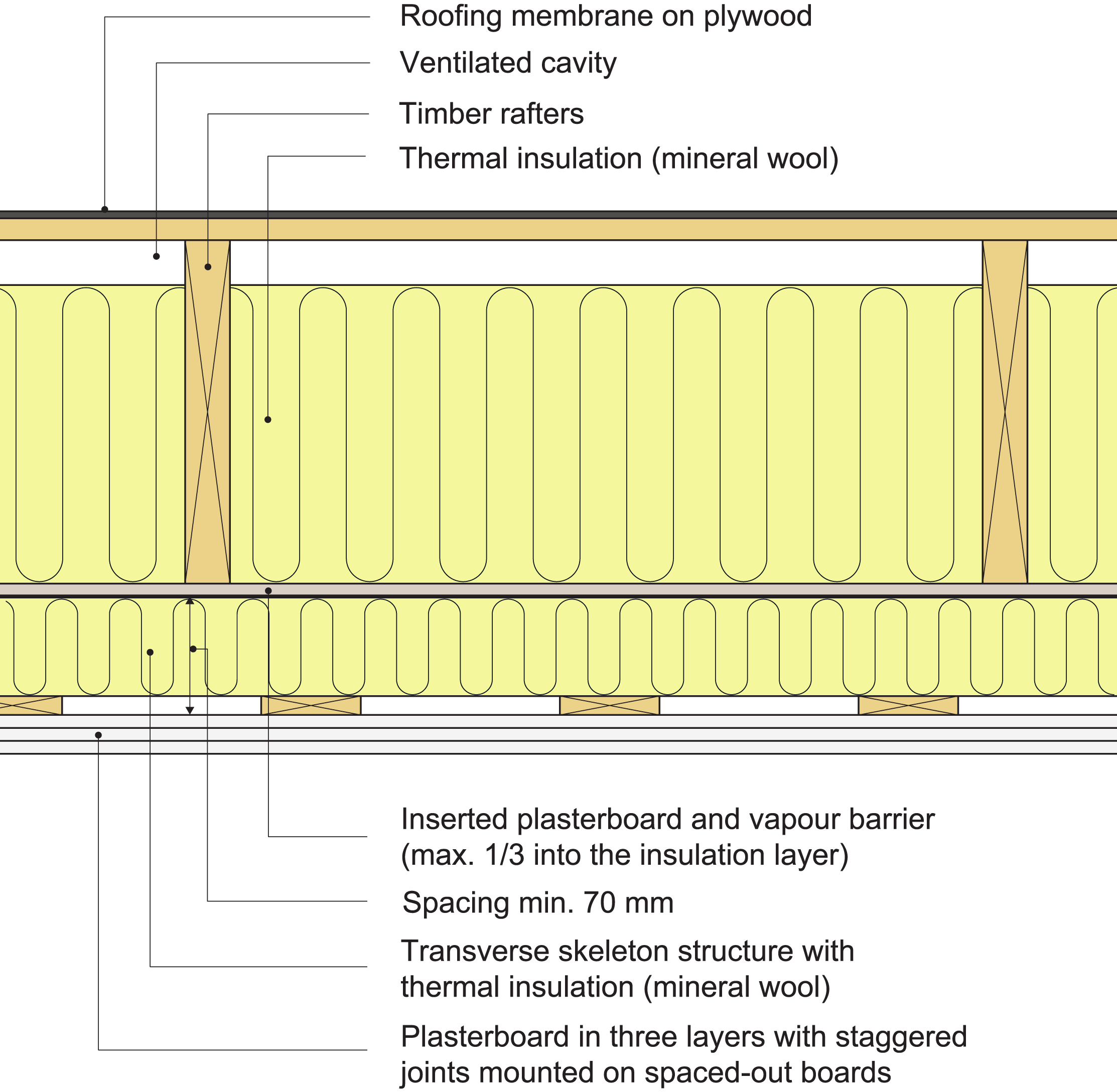

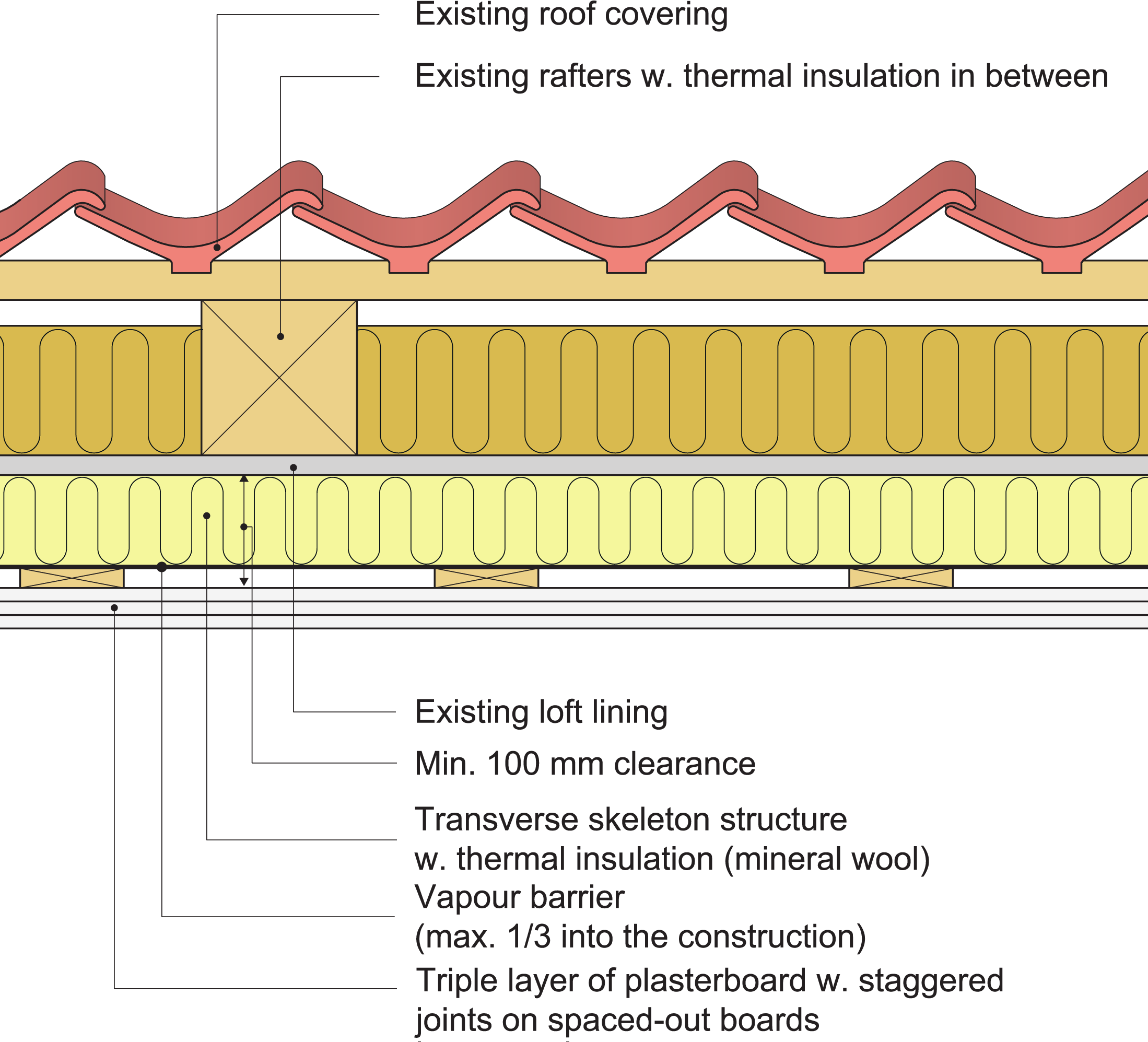

Construction

Vapour barriers in roofs must be installed on the warm side of the thermal insulation or extended slightly into the thermal insulation from the warm side (depending on the specific moisture load class (see Section 1.3.2, Warm Roofs)). In this way, the risk of a high relative humidity or condensate build-up on the underside of the vapour barrier is avoided.

A vapour barrier must be installed and trapdoors and other openings leading to the loft space must be sealed off before heating the building, as moisture from the building process might otherwise migrate into the roof assemblies, causing moisture build-up.

Joints, penetrations, and intersections must normally be executed on firm decking of 15-mm plywood sheets for example. Firm decking is required to enable tape joints to be compressed effectively and thus achieve permanent tightness. In some cases, prefabricated penetrations are available which can themselves provide firm decking.

Joints and intersections are executed using an overlap of at least 50 mm. These are normally installed using clamps which should be mounted using a hand-held clamp gun to avoid damaging the vapour barrier. To achieve airtightness, all joints must be secured further by bonding, using tape, butyl tape sealant, foil adhesive, or caulking compound. Compressed joints cannot, in themselves, be regarded as airtight.

Electrical wiring and similar installations in loft spaces should be run below the vapour barrier to avoid perforating it. This could be achieved by installing the vapour barrier 45–50 mm into the thermal insulation layer.

If the vapour barrier is damaged during installation, it must be repaired or replaced.

Examples of joining vapour barriers are shown in Figure 5. Examples of vapour barrier joins at penetration points for roofs with continuous and discontinuous roof coverings are shown in Sections 7.2.1 and 7.3.1, respectively.

Further information on vapour barriers and airtightness can be found in:

- SBi Guidelines 224, Moisture in Buildings (Brandt, 2013)

- SBi Guidelines 214, Klimaskærmens lufttæthed (Airtightness in the Building Envelope) (Rasmussen & Nicolajsen, 2013)

- Dampspærrer – monteringsdetaljer (Vapour Barriers – Installation Details) (Byg-Erfa, 2015a)

- Dampspærrematerialer og fugttransport – væg- og loftkonstruktioner (Vapour Barrier Materials and Moisture Transport – Wall and Ceiling Structures) (Byg-Erfa, 2015b)

- Bygningers lufttæthed – tæthedskrav, bygningsudformning og måling (Airtightness in Buildings – Tightness Standards, Building Design, and Measurement) (Byg-Erfa, 2013)

- Lufttæthed i ældre bygninger – efter renovering og fornyelse (Airtightness in Older Buildings – After Renovation and Replacements) (Byg-Erfa, 2016a)

Figure 5. Vapour barrier joints must be made with an overlap of at least 50 mm joined with adhesive tape (a), or by affixing them using sealant tape or glue (b). Airtightness can only be achieved when the joint is executed on firm decking. The most reliable joint (c) is achieved by either taping or bonding coupled with compression. Although formerly commonly practiced, compressed joints (d) not affixed by tape or adhesive will not be airtight (Brandt, 2013).

2.2 Roof Drainage

2.2.1 Building Regulations Provisions

The 2018 Building Regulations specify that rainwater and snow melt must be ‘able to drain off efficiently’. Rainwater must be discharged via gutters or downpipes to a drainage system’ (BR18, § 338). However, gutters and similar systems can be omitted in buildings in particularly open locations (such as holiday homes) and in minor buildings such as garages, outhouses, and sheds, unless special provisions issued by the building authorities apply. Care must be taken to drain the water away from the building and to ensure that it will not cause inconvenience to roadways or neighbouring sites (cf. Section 1.4 in Byggereglementets vejledning om fugt og vådrum (Building Regulations Guidelines for Moisture and Wet Rooms) (Ministry of Transport, Building and Housing, 2018c)).

As a result of the provisions of the Building Regulations regarding water drainage, roofs and roofing underlayment must be constructed with well-defined falls in both new build and renovations. If the roof slope is steeper than 1:40, corresponding to 2.5 cm per m, roof run-off will normally drain away efficiently (cf. Section 1.4 in Byggereglementets vejledning om fugt og vådrum (Building Regulations Guidelines for Moisture and Wet Rooms) (Ministry of Transport, Building and Housing, 2018c)).

The slope is normally directed towards a roof outlet or a gutter (eaves gutter). Roof pitch is of vital importance for roof drainage.

Ensuring reliable roof drainage in pitched roofs (pitch ≥ 10 °) is typically easy to achieve, except at eaves where water will sometimes accumulate on the roofing underlayment if the eaves are not designed correctly.

Flat roofs (with a slope of less than 10 °) require minimum falls of 1:40 (i.e., 25 mm per m or approx. 1.4 °). Locally, in (in small areas) falls as low as 1:50 may be acceptable due to executional tolerances. If possible, falls should be steeper to avoid depressions which cause pooling on the exposed roof surface.

Falls in valleys and cricket intersections can be reduced further (e.g., to 1:165). However, using such shallow falls requires firm decking, corresponding to a deflection of maximum 1:400 of the effective span to allow for snow load.

Steeper slopes will reduce the risk of water penetrating roof coverings with overlapped junctions. Minimum roof pitch recommendations exist for many roof coverings to ensure watertightness (see Section 5.1.3, Roof Pitch and Areal Weight).

2.2.2 Preconditions for Downpipe Sizing

Downpipes or vertical rainwater drainage pipes can be sized according to the rules in DS 432, Code of Practice for Sanitary Drainage - Wastewater Installations (Danish Standards, 2009) (BR18, § 70).

The rules presuppose a fill-factor (f) of 1/3 in vertical pipes. This can be achieved only where inlet conditions are ideal (e.g., where the inlets have rounded edges and are correctly designed). The following fill-factors (f) are normative for ordinary installation by skilled workmen:

- Inlet from all sides f = 1/3

- Inlet from one side (gutter) f = 1/5–1/4

- Inlet from two sides (gutter) f = 1/4–1/3.

Roof run-off is usually calculated using a rainfall intensity of 0.014 l/(s · m2) corresponding to 140 l/(s · ha). Please note that for roof terraces, balconies, and roofs with a risk of pooling (’bath tubbing’), rainfall intensity is usually calculated using 0.023 l/(s · m2), corresponding to 230 l/(s · ha) due to the risk of damage to the building.

Allowing for future climate changes, rainfall intensity should be multiplied with the climate factors shown in Table 6.

Table 6. Climate factors which can be used to allow for future climate changes depending on the expected lifespan of the structure. The parameter n denotes the probability of rainfall events exceeding the design rainfall intensity in one year. For example, a structure with an expected lifespan of 100 years for a ten-year rainfall event will have a climate factor of 1.3. This indicates a 30% increase in expected rainfall volume compared to the present (Danish Standards, 2009).

Rain return period | 2 years | 10 years | 100 years |

|---|---|---|---|

N | ½ | 1/10 | 1/100 |

Climate factor | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

The climate factors are calculated for an expected lifespan of 100 years. Consequently, when using the climate factor, consideration must also be given to the technical lifespan of the construction overall. For a shorter lifespan, the factor will be reduced proportionally to the reduction in expected lifespan.

If flooding caused by a blocked drain might result in water entering the building structure, a minimum of two downpipes should be installed (with separate discharge stacks, if possible), eaves overflows, or chutes in the parapet. This will be the case for many flat roofs with kerbs around the entire perimeter of the roof (see Section 2.2.4, Draining Flat Roofs and Section 5.7.3, Roof Slope for Membrane Roofs).

For detailed information on sizing rainwater installations (see DS 432 and SBi Guidelines 255, Afløbsinstallationer – systemer og dimensionering (Wastewater Installations – Systems and Sizing) (Brandt & Faldager, 2015)).

2.2.3 Draining Pitched Roofs

For pitched roofs with a roof covering of tiles, corrugated sheets, slate, or similar materials, rainwater is led to a gutter, a downpipe, and into the discharge system (normally a grated gully).

Runoff from thatched roofs and shingle roofs is normally discharged directly to the ground. Here, splashing may be reduced using rounded stones where the roof run-off hits the ground.

Gutters are often designed in a semi-circular shape, but other shapes exist (e.g., trapezoidal and rectangular). They are most often made of rigid PVC or zinc, but copper and stainless steel are also occasionally used (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Examples of gutter profiles.

Gutters are normally installed with a 2‰ fall but can be installed without falls if an oversized gutter is used (Brandt & Faldager, 2015).

Gutters concealed in the overhang should be avoided as the overhang may decay if the gutter overflows (this will not be visible immediately).

The flow capacity of a gutter depends on its size, shape, and fall. To avoid too great a distance between eaves and gutter, the usual practice is to install gutters with a very slight fall or no fall at all. For horizontal gutters, only their size (cross-sectional flow area) and geometric shape affect the flow capacity. The capacity of a semi-circular gutter is:

hvor

This capacity can be increased by 40% by a longitudinal fall of more than 2‰, or in gutter runs of more than 6 m. Bends placed less than 2 metres from the outlet will reduce the flow capacity as follows:

- 10% for horizontal gutters with round-edge outlets,

- 20% for horizontal gutters with sharp-edge outlets,

- 25% for gutters with longitudinal falls.

Equation (1) and the adjustment values can, with adequate approximation, also be applied to rectangular gutters and other profiles.

Figure 7 shows gutter capacity according to cross-sectional flow area, catchment area, and rain intensity. The figure applies to pitched roofs with a slope of less than 50 °.

Figure 7. The capacity of horizontal gutters conditional on rain intensity, gutter size, and location of downpipe (Brandt & Faldager, 2015).

Example 1 (From SBi Guidelines 255)

According to Figure 7, in an area with a rain intensity, i, of 130 l/s per ha, a semi-circular gutter with a diameter of 100 mm is capable of draining a catchment area of 64 m2 if the downpipe is placed at the end of the gutter (L1/L1 + L2 = 1), or 128 m2 if the downpipe is placed at the centre (L1/L1 + L2 = 0.5) (Brandt & Faldager, 2015).

Downpipe Capacity

The quantity of water a downpipe can discharge depends on the shape of the inlet (i.e., whether the shape of the inlet is round- or sharp-edged). Furthermore, the capacity is conditional on the water being discharged into the downpipe from one or two sides. Data has been obtained for the flow capacity of a downpipe according to the Wyly-Eaton equation:

where:

The Wyly-Eaton equation only applies to fill-factors of less than approx. 1/3. Furthermore, it assumes that the discharge flow forms a hollow cylinder inside the pipe after the flow velocity has peaked.

For downpipes with inlets from two sides, the fill-factor is 1/4, whereas for a downpipe with an inlet from one side, it is 1/5. These fill-factors were determined for sharp-edged inlets. For round-edged inlets, the calculated increase is 10–30%.

The maximum capacity of downpipes placed at one end of a gutter corresponds to approx. 70% of the capacity of a centrally placed downpipe. Figure 8 shows the capacity of a downpipe relative to downpipe dimension, rainfall intensity, catchment area, and position. Design rainfall intensity can normally be selected to correspond to one overload per year for separate systems and one overload every two years for combined systems. For gutters on buildings close to pavements subject to heavy pedestrian traffic, the design intensity could be increased (see SBi Guidelines 255, Afløbsinstallationer – systemer og dimensionering (Wastewater Installations – Systems and Sizing), 7.4.5 Skrå tage (Sloping Roofs) (Brandt & Faldager, 2015)).

Downpipes can be placed on the outside of the building, and they will normally be made of the same material as the gutter. Downpipes near to pavements and subject to heavy pedestrian traffic should be made of a robust material such as stainless steel or hot-galvanised steel for roughly the last 2 metres, to be able to resist major mechanical impact.

Example 2 (From SBi Guidelines 255)

According to Figure 8, in an area with a rainfall intensity, i, of 130 l/s per ha, an 80-mm downpipe is capable of draining 200 m2 of catchment area if placed at the end of the gutter and 290 m2 if placed centrally in the gutter (Brandt & Faldager, 2015).

In combined systems, downpipes from sloping roofs can be connected to the general discharge system in the following ways:

- They can be connected in a closed rainwater pipe to a gulley measuring at least 0.2 metres.

- They can be connected across the surrounding area (e.g., via an open conduit sloping towards a gully). If this solution is anticipated to cause a nuisance, it may be prohibited by the authorities. The solution should not be applied in slab-on-ground constructions, and the ground must have a minimum fall of 25‰ away from the building. It is important that a fall away from the building is incorporated when backfilling excavated areas.

Figure 8. Downpipe capacity relative to rainfall intensity, dimension, and location of downpipe (Brandt & Faldager, 2015).

2.2.4 Draining Flat Roofs

Roof Rainwater Outlets

On flat roofs, rainwater will slowly flow towards the outlets which are normally installed to feed from all sides (see Figure 9). For roofs covered with roofing felt, stainless steel outlets are normally used, while plastic outlets can be used for foil-covered roofs. The drainage capacity of roof outlets for flat roofs is relative to the size of the pipe as well as the design of the outlet and grating. The drainage capacity will vary considerably from below 1 l/s to almost 20 l/s.

The design rainfall intensity should correspond to overload once every 5–10 years.

Care must be taken to thermally insulate discharge pipes, if required, to avoid condensate build-up.

More examples of roof outlets in flat roofs with roofing membranes are shown in Section 7.3.3, Flashings Roof Outlets.

Figure 9. Example of a stainless-steel roof outlet countersunk into the roof (shown here with 2 layers of bituminous felt). The countersinking ensures that water can be discharged to the outlet. The roof outlet comes with a layer of pre-installed bituminous felt to ensure effective adhesion between the outlet and bituminous felt layer. The intersection between the outlet penetration and the vapour barrier must be sealed to avoid warm indoor air from entering the roof assembly.

Due to slow inflow from minor depressions in the roof, there will be a risk of ice dams forming near the roof outlets and blocking them during winter. Therefore, it is preferable to install interior outlets, as these are kept frost-free by building heating. If placed in an eave overhang , or a similar exterior location, outlets must be heated using trace heating. Trace heating is commonly used in places where there is a risk of ice forming such as in box-receivers and side outlets.

The distance between roof outlets should not exceed 14.4 metres and the distance from the gable should not exceed 7.2 metres. Assuming that there is an unbroken fall of at least 1:40 across the roof, a greater distance is acceptable (see Section 5.7.3, Roof Slope for Membrane Roofs).

Roof outlets supplied with pre-installed membranes ensure effective adhesion between outlet and roof covering.

Roof outlets may also be supplied with side outlets to a box-receiver (see Figure 10). The capacity of roof outlets with side outlets is substantially lower than that of roof outlets with vertical outlets. For the sizing of these outlets, please see manufacturer’s instructions. Outlets to exterior box-receivers must be installed with a fall towards the box-receiver. Pointing around the outlet will prevent moisture absorption in the wall. Box-receivers must be installed with overflow protection below the inlet level.

Figure 10. çThe roof outlet flange has a pre-installed membrane to ensure effective adhesion between outlet and membrane. The inflow to the roof outlet must be placed above the outlet to the box-receiver.

On flat roofs, flashings surrounding chimney stacks, roof vent cowls, and roof lights are vulnerable. To protect flashings (and the supporting roof structures) against excessive stress load it will be necessary to do the following:

- Roof outlets should be placed at the lowest points in the roof. Allowances must be made for any deflection and setting of the structure.

- A minimum of two roof outlets should be installed irrespective of sizing outcome.

- A grate should be fitted to the outlet. Please note that the design of the grating may seriously affect the flow capacity of the outlet. For the grating to enhance capacity, however, regular maintenance is necessary, especially where considerable leaf-fall is expected.

- Roof outlets should be placed far enough away from flashings (usually 0.5 metres as a minimum) to allow the flashings around the roof drain hopper and other flashings to be adequately executed.

If concealed joints are necessary inside the structure through which the outflow from roof outlets is drained, these must be welded.

The draining of flat roofs is sometimes affected via box gutters. Like the roof surface itself, these must be installed with a well-defined fall towards an outlet. The fall should be a minimum of 1:100 (i.e., 10 mm per m). Box gutters should also be robust and capable of resisting impact from ice during winter. They should have an emergency outlet, such as a pipe with a minimum diameter of 75 mm at either end, or be fitted with overflow protection so that the water will never flow over the top of the box gutter. If U-bends are used, they must be placed in a frost-free position and the roof outlets require careful cleaning and extra maintenance to avoid blockage.

Roof outlets are connected to downpipes installed as ordinary vertical waterpipes. The interface between the roof drain hopper and the inside downpipe must comply with tightness requirements for rainwater pipes in DS 432, Code of Practice for Sanitary Drainage – Wastewater Installations (Danish Standards, 2009). After renovation when replacing roof outlets for example, the discharge systems will quite often prove not to be tight if debris damming occurs. This should be factored in when sizing the drainage system, using grated outlets and by establishing an emergency overflow for example.

In combined systems (i.e., discharge systems where wastewater, rainwater, and drainage water converge into the same rainwater pipe) run-off from flat roofs can be connected to the existing discharge system in the following ways:

- It can be connected to a closed rainwater pipe via a roof outlet measuring, as a minimum, 0.2 metres.

- It can be connected directly to the property’s discharge pipes without passing through a U-bend. This method is restricted to flat roofs not intended for occupancy (due to odour nuisance) and where the position of the roof outlet relative to the ventilation stack of the discharge pipe is constructed as shown in Figure 11.

Connecting roof run-off to a vertical vented combined rainwater pipe must be executed as shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11. When connecting a roof outlet to a vertical vented combined rainwater discharge pipe, care must be taken to ensure that ventilation can also take place in rainy weather. The connection must be carried out using one of the two solutions shown in the drawing so that the rainwater discharge pipe can be sized as vented.

Roof run-off can be led directly to a discharge system without passing through a grit trap if it can be ascertained that the inlet area is free of twigs, leaves, or similar debris common in multi-storey buildings. Nevertheless, the inlet should be protected by a grating or a similar filter.

Special Roof Drainage Systems

Special types of roof outlets capable of draining sufficient rainwater and air to provide full-bore flow in the connecting waterpipes have been developed. Drainage systems of this type are known as ’UV-systems’. Full-bore flow enhances the utilisation of pipes, which can be executed in smaller dimensions and be installed horizontally across long distances.

These drainage systems are installed and sized according to specific methods relative to the design of the roof outlet and the degree of ponding occurring on the roof. If possible, UV-outlets with vertical outlets should be used. The outlet should intersect the roof structure and the horizontal pipe-run be installed below the roof.

It is now common practice to run pipes inside the insulation layer, therefore roof outlets with horizontal discharge are often used. However, horizontal pipe runs should be avoided as far as possible as there will always be a risk of undetected leakage in concealed pipes. If necessary, the waterpipes (and roof outlet) inside the structure should be compression-tested before sealing the roof.

UV-systems should be supplied with a pre-installed membrane, ensuring adequate adhesion between the outlet and the membrane.

The actual roof outlet should also be included in the leaktightness test.

For renovations, roof outlets with a side outlet may be used in some cases.

The discharge system can be exposed to both positive and negative pressure and must therefore be capable of resisting stress loads comparable to at least ± 300 kPa in relation to atmospheric pressure. It is common practice to test the systems for leaktightness before they are put into operation. UV-systems are developed and tested as systems solutions (i.e., using the same brand of components throughout the system). When installing UV-systems typically the manufacturer will specify the sizing, will determine the detail design required, and will supply the relevant components.

Emergency Overflow from Flat Roofs

For flat roofs with a parapet, an emergency overflow independent of the normal discharge system should be installed to prevent any damage to the fabric of adjoining building components in the event of ponding on the roof. The emergency overflow system must kick into action in the event of ponding due to blockage of the roof drain hoppers caused by ice, twigs, or leaves, or if the entire discharge system is blocked due to extreme rainfall events.

The overflow can be installed as a roof outlet fitted with raising rings to lead the water away via a separate drainage pipe or as openings in, or outlets from, the parapet (see Figure 12). The emergency overflow must be positioned below exhaust and intake vents, with its lower edge positioned 50–70 mm above the upper edge of the roof outlet (See Figure 13). An emergency overflow with a diameter of approx. 80% of the capacity of ordinary outlets should, as a minimum, be installed for every second roof outlet. The emergency overflows ensure that the water will never pool higher than the roof flashings – typically 150 mm above the finished roof surface. Emergency overflows should be installed so that the water is drained away from the façade, using chutes for example.

Examples of how to position emergency overflows on flat roofs are shown in Section 5.7.3, Roof Slope for Membrane Roofs.

Figure 12. Techniques for installing emergency overflows to flat roofs.

- Roof outlet with raising rings and separate discharge pipe

- Aperture or opening in parapet

- Parapet outlet (see Figure 13).

Figure 13. For roof surfaces between a building and a parapet, overflows are installed in the form of apertures, overflow outlets, or large parapet outlets to mitigate ponding, which may damage the fabric of the building. There must be no junctions on the section of the emergency overflow extending through building parts. Please note that for large roof surfaces, the emergency overflow must be positioned so that its lower edge is placed at least 50 mm below the flashing height (min. 150 mm).

2.2.5 Draining Green Roofs

The run-off factor from green roofs is significantly lower than for ordinary flat roofs, a factor that should be considered when sizing the system. On an annual basis, approx. 50% of the water ends up in the discharge system only.

Nevertheless, green roofs have a limited mitigating effect in extreme rainfall events and the discharge system must therefore be sized like that of other flat roofs (enabling them to handle extreme rainfall loads) and emergency outlets must be installed.

Valleys and the areas around roof outlets should normally be kept free of vegetation to avoid blockages.

Roof outlets must be cleanable and should be cleaned and checked twice a year.

UV-systems should not be used for green roofs, as there will rarely be sufficient water available to flush the pipes.

Guidelines for water discharge from green roofs are also provided in Section 5.11, Green Roofs.

Figure 14. Basic diagram of integrated roof outlet in a green roof constructed as a duo-roof. The discharge from the membrane’s upper side has been lowered approx. 10 mm to allow free discharge from the membrane (see Figure 9).

2.2.6 Special Outlets

Discharge onto underlying roof surface

For buildings with multi-level roofs, it is often desirable to discharge run-off from higher-level roofs to lower-level roofs, using downpipes to discharge water freely onto the lower-level roof surfaces. This free discharge onto a roof surface may cause mechanical wear and tear to the roofing materials exposed to the streaming water, and so-called deflector plates made of strong and corrosion-proof materials should therefore be fitted. For roofing made of bituminous felt or membranes, an extra membrane layer should be fitted below the downpipe nozzle.

Chutes should not be fitted above circulation areas.

Outlets From Roof Terraces

Rainwater must be drained away from roof terraces and similar areas to prevent nuisance and damage. Therefore, outlets or chutes will normally be fitted.

Outlets on roof terraces must be positioned at the lowest level of the roof. When determining this position, due consideration must be given to any expected deflections of the deck.

Connecting outlets from roof terraces to the general discharge system must be carried out as specified for roof outlets. Outlets on roof terraces must be checkable and cleanable. Roof outlets should be designed to drain all levels in a terrace assembly.

Figure 15 shows an example of an integrated outlet in a roof terrace on a thermally insulated roof.

Figure 15. Basic diagram of integrated roof outlet in roof terrace constructed as a duo-roof. The discharge from the membrane’s upper side has been lowered approx. 10 mm to allow free discharge from the membrane (see Figure 9).

Parking Deck Outlets

Roof outlets in parking decks must be capable of resisting vehicular traffic loads. Therefore, they are often made of cast iron and a roofing membrane fixed with a clamping ring to create a robust joint. Roof outlets must be securely fixed, for example by concreting them in to avoid them being moved by braking and accelerating cars (see Figure 16).

In certain cases, such as in large parking facilities, local authorities may stipulate that rainwater discharge from parking decks be led through grit and oil traps.

Figure 16. Schematic of outlet on thermally insulated parking deck in a warm roof installation. The membrane is mechanically secured to the outlet using a clamping ring.

2.3 Roof Ventilation

The small amounts of moisture which will inevitably migrate into the roof structures must be removed to avoid the harmful accumulation of moisture in the roof structure over time. In many roof structures, moisture is traditionally removed through ventilation. Cold roofs, for example, are installed as vented assemblies where the ventilation air removes moisture which has either migrated into the structure form the inside or has penetrated the structure from above.

However, this is not the case with all assembly types, and it is essential to know the preconditions for other solutions (cf. Section 1.3.1, Cold Roofs).

2.3.1 Preconditions for Removing Moisture by Ventilation

For a vented roof structure to function, a typical precondition is that it is sufficiently vapour-impermeable and airtight. If large amounts of moisture migrate into the roof structure, due to leaking joints or penetrations in the vapour barrier for example, even powerful ventilation will not always be capable of removing the moisture.

The roof structure is ventilated with ‘vent openings’, at eaves, ridges, in gable ends, and elsewhere. Inside the roof structure, air will flow through ‘vent spaces’, or ‘spaces’ (loft spaces, apexes, and crawl spaces). Differences in wind pressure and temperature (the stack effect), cause air to flow through the structure, removing moisture.

Ventilation systems must include;

- unutilised loft spaces (including crawl spaces and apexes),

- vent space between thermal insulation and (usually vapour-impermeable) roofing underlayment in couple roofs,

- a gap between thermal insulation and roof covering in cases where no underlayment is used,

- a cavity space between roof covering and underlayment (regardless of whether the roofing underlayment is vapour-permeable or vapour-impermeable).

Figure 17 is a schematic diagram of the venting within a collar roof with a cold crawl space, apex, and vapour-impermeable roofing underlayment.

Figure 17. Schematic of vented collar roof with vapour-impermeable roofing underlayment. The ventilation system includes the crawl space and vent spaces between the thermal insulation and roofing underlayment, and apex. Besides venting below the roofing underlayment, the space between underlayment and roof covering must also be vented. Eaves-to-ridge ventilation occurs via openings at the eaves and ridge (as shown), where thermal uplift (the stack effect) drives the vent air through the roof structure. A precondition for this to function is that the vapour barrier is tight.

Periodically, moisture from the outside air briefly enters vented roof structures (e.g., when the structures are colder than the dew point temperature of the outside air). This moisture is removed by venting when the relative air humidity is reduced once again.

For roof coverings with a low heat capacity and low or no moisture absorption capacity (e.g., steel sheets), the added moisture may lead to the precipitation of condensate on the underside, which must be removed by roofing underlayment or temporarily removed by a condensate absorber for example (see Section 5.5, Metal Sheets). Special provisions apply to the removal of condensate on the underside of zinc and copper roofs (see Section 5.6, Zinc and Copper (and Aluminium)).

For certain overlapping types of roof covering (such as roof tiles), small quantities of water can penetrate the roof from the outside and cause moisture absorption. Under-roof venting ensures quick drying and thus protects spacer bars, roof battens, and roof coverings. The need for ventilation is greater during winter when moisture levels in roof structures peak (see Section 5.2, Roof Tiles).

2.3.2 General Ventilation Guidelines

To avoid moisture problems, ventilation must be effective, and the following general guidelines must be complied with:

- The area of vent openings must be designed according to Table 7 or have a combined size corresponding to 1/500 of the built area.

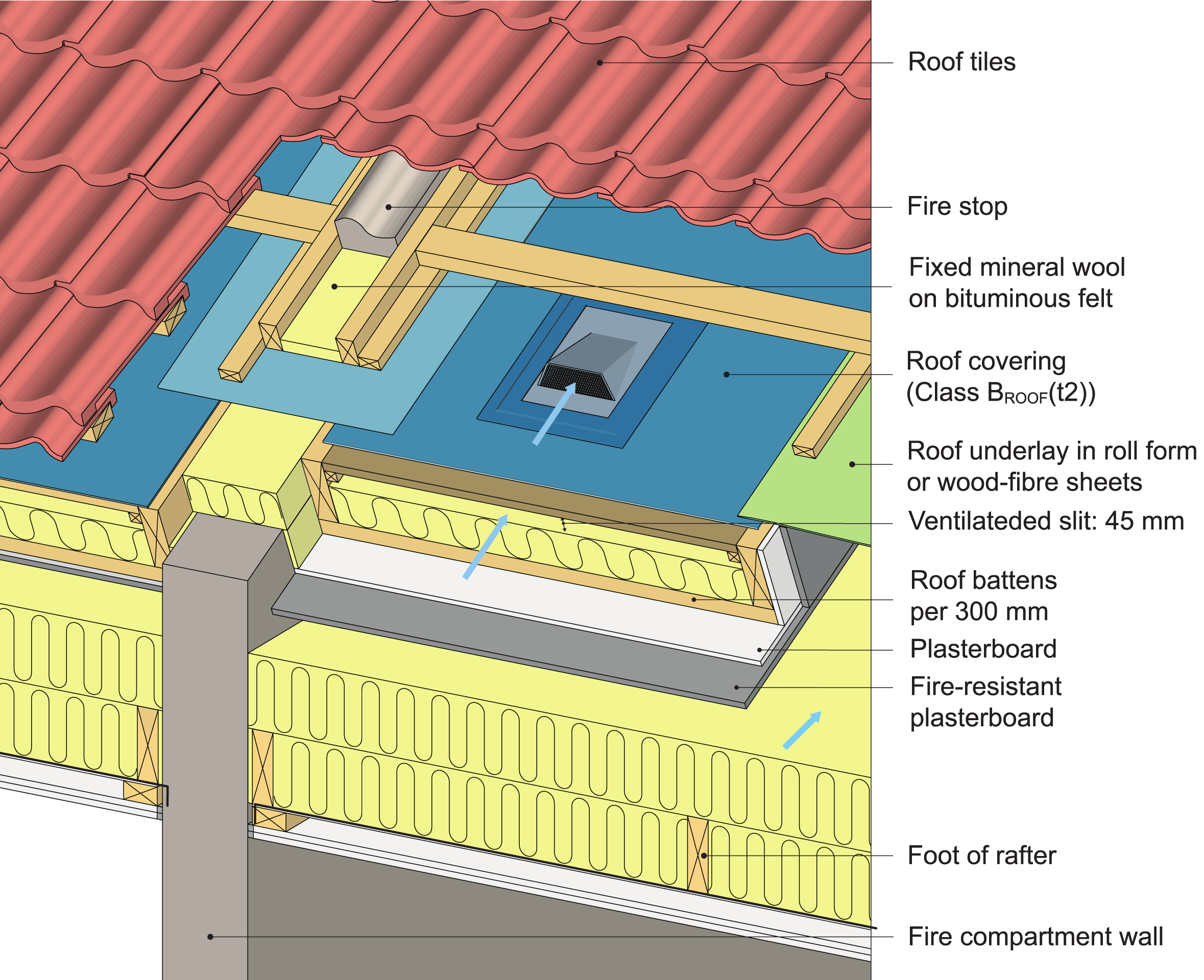

- Ventilation air must be evenly distributed. Vent openings should therefore be positioned to avoid any unvented areas. The roof must be vented where the hip, valley, roof lights, chimney, etc., block normal ventilation (see Figure 18). For pitched roofs, this can be achieved using roof vent tiles. For roofs fitted with roofing underlayment, supplementary roof vents should be fitted to the underlayment.

- Vent openings are normally fitted with a mesh to avoid ingress of birds, insects, or drifting snow. The insect mesh will reduce the airflow by approx. one half and the meshed vent openings must therefore be double the required net area. If an insect mesh is used, the height of the vent openings in the eaves must be 30 mm while, if the insect mesh is omitted, the required (net) height is only 15 mm. The size of the required vent openings in Table 7 includes insect mesh. The net area can be used in rare cases when an insect mesh is omitted.

Table 7. The required size of vent openings or number of roof vents per roof truss for buildings with a building depth of up to 16 metres (the distance between facades). The table applies to a roof truss spacing of up to 1.2 metres. For roofs without roofing underlayment, the table applies to vent openings in the space between thermal insulation and roof covering. For roofs with underlayment, the table applies to vent openings in the space between thermal insulation and underlayment. For roofs with underlayment, it will usually be necessary to also ventilate the space between underlayment and roof covering.

The table specifies two figures indicating the size of the required vent openings: 1) gross area of the overall required size with insect mesh/bird grating in all vent openings and, 2) net areas of the overall required size without insect mesh or bird grating. The figures in front of the slash indicate the gross height/area while the figures after the slash indicate the net height/area.

Manufacturers of roof vents or insect meshes must declare the reduction of airflow caused by the mesh if the airflow reduction is less than half of what it would be in a vent opening or roof vent without a mesh.

There must always be vent openings at the eaves. For shallow roof pitches (slopes <10 °), ridge ventilation should be avoided to mitigate negative pressure in the roof assembly. Discontinued roofing includes roof tiles and roofing sheets, while continuous roofing will usually consist of roofing membranes (cf. Section 5.1, Types of Roof Covering).

House depth | Vent opening at* the base of each rafter | Total ridge vent opening | Type of roof covering | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Roof vents | Spaces | |||||

Roof type | m | Height in mm (Height with/without insect mesh | cm2 (Area with/without insect mesh) | Height in mm (Height with/without insect mesh) | Discontinuous roof coverings | Continuous roof coverings |

Gable roof ≥10 ° slope | ≤ 16 | 30/15 | 200/100 | 20/10 | x | x |

Mono-pitch roof or lean-to roof ≥10 ° slope | ≤ 8 | 30/15 | 100/50 | 20/10 | x | x |

≤ 16 | 30/15 | 200/100 | 20/10 | x | x | |

Flat roof <10 ° slope | ≤ 16 | 30/15 | No openings at the ridge and no roof vent cowls | x | ||

*) In areas subject to requirements to safeguard against flame spread, the height of vent openings at the eaves in certain building types must be max.

30 mm, and the length must be min. 300 mm (DBI Fire and Security, 2007).

30 mm, and the length must be min. 300 mm (DBI Fire and Security, 2007).

Other general guidelines for roof ventilation:

- At the eaves level, where vents are behind the gutter, there must be free air access to the vent opening, including at least 20 mm of clear space between the gutter and the vent opening or wall.

- For house depths exceeding 16 metres, the ventilation design should be based on a moisture calculation. In this case, it would be advantageous if cross ventilation could be established so that the building is also vented in a lengthwise direction.

- The size and number of vent openings is relative to the size and geometric design of the roof (see Table 7). Alternatively, the roof can be vented at a rate corresponding to 1/500 of the built area.

2.3.3 Guidelines for Ventilation of Pitched Roofs

To provide sufficient venting of pitched roofs (slope ≥10 °), the general guidelines in Section 2.3.2, General Ventilation Guidelines must be complied with. Further, the following guidelines must be met:

- Ventilation should be driven by both wind pressure and the stack effect. Therefore, eaves-to-ridge ventilation should be installed.

- For renovations where airtightness is believed to be poor, unvented roofing underlayment should not be used.

- Where normal eaves-to-ridge ventilation is blocked (at valleys, dormers, roof lights, hips, and chimneys), alternative methods of venting the roof must be used (see Figure 18).

Figure 18. Where normal eaves-to-ridge ventilation is blocked (at valleys, dormers, roof lights, hips, and chimneys, etc.), alternative methods of venting the roof must be used such as roof vents in the roofing underlayment and vent tiles in the roof covering.

Figure 19. In all roofs fitted with roofing underlayment, the space between underlayment and roof covering must be vented and, in vapour-impermeable underlayment, the space between underlayment and thermal insulation must also be vented. This figure relates to buildings with a building depth or length of max. 16 metres.

a. The most effective ventilation method for open loft spaces is eaves-to-ridge.

c. Couple roofs and collar roofs are vented using eaves-to-ridge venting.

e. For collar roofs in short buildings (less than 16 metres long), ventilation at the gable-end apex may supplement or replace part of the ridge venting.

b. In open loft spaces in short buildings (less than 16 metres long), ventilation at the top of the gable ends can supplement or replace part of the ridge venting.

d. Couple roofs and collar roofs are vented using eaves-to-ridge venting.

f. For collar roofs in short buildings (less than 16 metres long), ventilation at the gable-end apex may supplement or replace part of the ridge venting.

2.3.4 Guidelines for Ventilation of Flat Roofs

To ensure adequate venting of flat roofs, the general guidelines in Section 2.3.2, General Ventilation Guidelines, must complied with. Furthermore, the following guidelines must be met:

- For shallow roof pitches (slope < 10 °), ventilation is exclusively wind-driven, and it must be guaranteed. Therefore, the wind must have free access to the vent openings.

- For building depths up to 16 metres, ventilation is affected exclusively via openings in the eaves.

- Vent openings are usually established at the eaves (e.g., in the soffit or parapet). The optimal conditions for ventilation airflow are achieved using eaves-to-eaves ventilation.

- There will normally be a permanent negative pressure across the whole roof surface. Consequently, roof vent cowls must not be used, because the negative pressure will be transmitted to the vent space where it may cause moist air to be drawn into the roof assembly.

- For ventilation through masonry in a parapet, ventilation air is supplied via openings with an area corresponding to the guidelines for flat roofs in Table 7.

- The empirical effective height of the vent space above the thermal insulation in a flat roof assembly must be at least 45 mm. This can be achieved by specifying that the thermal insulation height be secured by metal wire, for example.

- If eaves adjoin a wall, a covered vent opening may be fitted (see Figure 20). This solution must not be used in both sides of a vented cavity space, as differences in pressure generated by the wind will not be able to draw air through the vent space, because negative pressure will form across the whole roof.

- When vent spaces become blocked (e.g., in large roof lights and in L-shaped buildings), openings may be made from a blocked vent space to the vent spaces in the neighbouring sets of roof trusses. If the openings are made by drilling holes or by chiselling them out in rafters or other loadbearing timber elements, documentation is required to prove that the static conditions remain satisfactory.

Table 8. Specification of gross area or height of vent openings at the base of the roof and eaves for vented roofs with a slope of less than 10 ° and a building depth of max. 16 metres. The table indicates two figures specifying the size of the required vent openings: 1) gross areas for the overall required size, including insect mesh or bird grating in all vent openings and 2) net areas for the overall opening without insect mesh or bird grating. The figures in front of the slash are gross heights and the figures after the slash are net areas. The ventilation type must be eaves-to-eaves (via vent openings in the parapet). The vent openings must be distributed evenly and be sized in compliance with the guidelines for flat roofs in Table 7. Roof vent cowls on the exposed roof area must not be fitted, as they will generate negative pressure in the vent space.

Roof type | Gross area/net area of vent space |

|---|---|

Gross area/net area of vent opening in parapet: 300/150 cm2 per m | |

Height of vent opening at eaves: 30/15 mm | |

Height of vent opening at eaves: 30/15 mm Vent opening facing wall: 30/15 mm (see Figure 20) |

Figur 20. A covered vent opening on a roof adjoining an exterior wall which renders normal eave-to-eave ventilation impossible. This solution must only be used on one side of a roof assembly. There must be an opening measuring min. 30 mm around the entirety of the vent opening.

2.3.5 Unvented Assemblies

Roofs not requiring ventilation (unvented assemblies), include the following roof types:

- Warm roofs where the underside and sides of the thermal insulation and the top of the roof covering are sealed by a vapour barrier. It is a precondition that the roof covering and vapour barrier are joined tightly so that moisture cannot migrate into the thermal insulation. The supporting structure is completely covered by thermal insulation.

- Cold roofs with a moisture-adaptive vapour barrier in which moisture that migrates into the assembly in cold weather will be removed by downward diffusion in warm weather. It is a precondition that the roof covering is warmed during summer through exposure to direct sunlight, so that the moisture that migrates into the structure during the winter can be removed during the summer. Special preconditions apply to the design of such assemblies which are available from the manufacturer of the moisture-adaptive vapour barrier.

- Cold roof assemblies constructed using composite roofing slabs with supporting parts in timber or steel. The slabs have integral vapour barriers (which should be moisture-adaptive to avoid moisture being absorbed by the assembly) and a membrane roof. It is a precondition that the vapour barrier is completely airtight. This places especially tough demands on the joints between the composite roofing slabs in the finished building. Likewise, it is a precondition that the composite roofing slabs are prevented from absorbing moisture during transport and the building phase.

- Cold couple roofs with an unvented roofing underlayment where moisture from the inside is removed by diffusion via the underlayment material. A precondition for using unvented underlayment is that the vapour barrier is airtight so that only modest quantities of moisture require removal. Venting the space between roofing underlayment and roof covering is necessary to remove moisture. Please note that open loft spaces, large crawl spaces, and apexes will require modest venting although a vapour-permeable roofing underlayment is used (cf. Section 3.2.2, Unvented Roofing Underlayment).

Examples of cold and warm roofs are shown in Section 1.3, Warm and Cold Roofs.

2.4 Heat Loss

2.4.1 Building Regulations – Energy Provisions

The roof assembly must be designed, constructed, converted, and maintained to avoid unnecessary energy consumption for heating and cooling purposes. This should, along with the remaining building parts in the building envelope, contribute to satisfying the provisions for thermal insulation in applicable Building Regulations (BR18, § 250–298) (The Danish Transport, Construction and Housing Authority, 2017). These energy provisions may also be met by applying the optional low-energy class (BR18, § 473–484).

Documentation showing that the energy provisions specified by the Building Regulations have been met must be done using the SBi Guidelines 213, Bygningers energibehov (Energy Requirement in Buildings) (Aggerholm & Grau, 2018) (BR18, § 251).

When calculating transmission areas, transmission loss, etc., DS 418, Calculation of heat loss from buildings (Danish Standards, 2011), must be used (BR18, § 256).

The Building Regulations specify various energy provisions which apply in different scenarios, for example, whether the construction is a new build, conversion, or renovation. For new builds, the provisions distinguish between residential housing or other types of building. Moreover, there are separate energy provisions for extensions and holiday homes, for example.

The Building Regulations’ provisions for airtightness are outlined in Section 2.4.3, Airtightness.

New Builds

The Building Regulation energy provisions for new builds are formulated as an overall performance requirement. Whole buildings must meet thresholds within an energy performance framework, which depend on whether the building is residential housing or another type of building. The energy performance framework specifies a building’s maximum permissible energy demand (e.g., for heating). The energy performance framework is supplemented by provisions for specific building parts. These supplements are for the thermal insulation of the building envelope as a whole (design transmission loss) and, for the minimum thermal insulation of building parts and linear thermal transmittance in joints (thermal bridges) (max. U-value and Ψ-value). These measures prevent unnecessary heat loss and condensation caused by thermal bridges and enhance comfort.

The U-value for a roof should be max. 0.20 W/m2K (BR18, § 257). This corresponds to a thermal insulation thickness of approx. 200 mm mineral wool, depending on the type of thermal insulation chosen and the quantity of wood in the thermal insulation layer for example. To meet the Building Regulations’ combined provisions for energy requirements, the typical U-values for new roofs will be between 0.08 and 0.12 W/m2K. The thickness is calculated using lambda-values (see Section 2.4.2, Thermal Insulation of Roofs). The U-value requirements correspond to thermal insulation thicknesses of approx. 300-400 mm when using mineral wool with a λ-value of 37 and a wood percentage of approx. 6%.

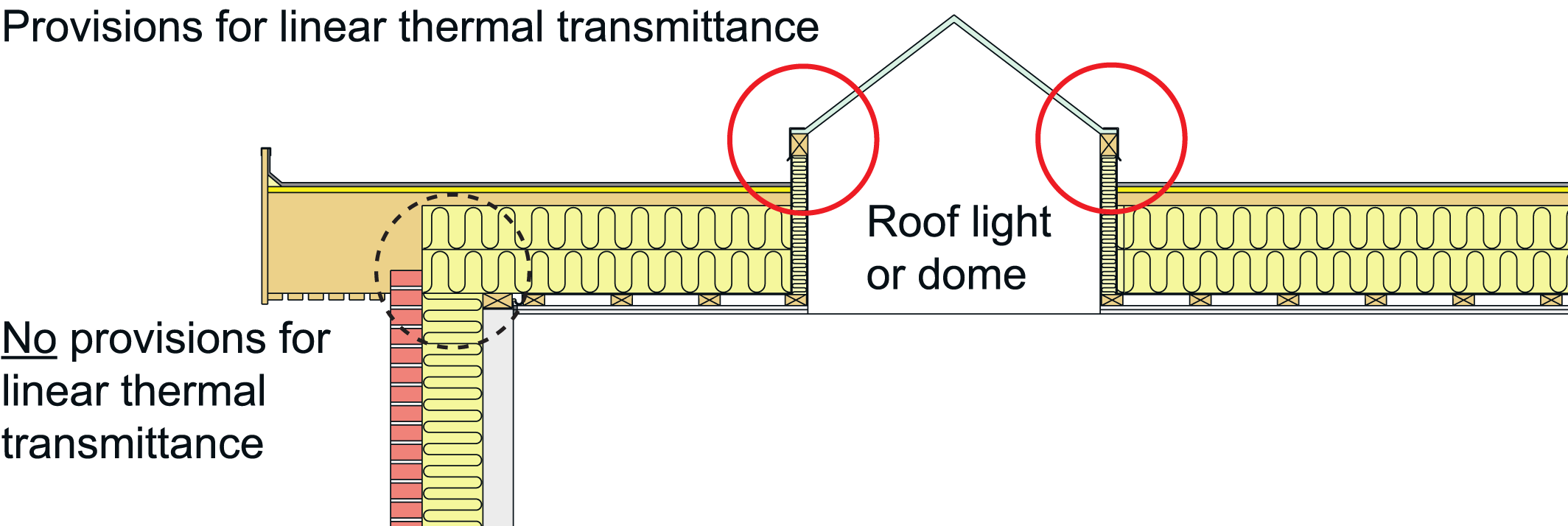

There are requirements regulating the linear thermal transmittance in the joints between roof assembly and roof lights or domes, as the linear thermal transmittance must be max. 0.20 W/mK (BR18, § 257). By reducing the linear thermal transmittance, the thermal bridge around roof lights and domes will also be reduced (see Figure 21). Conversely, there are no requirements regulating the linear thermal transmittance around interfaces between roof assemblies and exterior walls, as this is compensated for by the heat loss of the exterior surface area of the building (cf. DS 418, Calculation of heat loss from buildings (Danish Standards, 2011)). However, major thermal bridges should still be avoided.

Minimum requirements for building parts and linear thermal transmittance in interfaces between building parts in roofs are shown in Table 9.

Figure 21. Provisions for linear thermal transmittance in roof assemblies at the interface with roof lights and domes (red circle) while no provisions exist for the interface between roof assemblies and exterior walls (dotted circle).

Table 9. Minimum requirements for thermal transmittance (U-value) and thermal bridges in interfaces (linear thermal transmittance) for building parts used in roofs (BR18, § 257). In addition to the requirements regulating the actual loft and roof assembly, there are requirements for trapdoors to unheated spaces such as loft spaces.

Building Part | U-value [W/m²K] |

|---|---|

Loft and roof assemblies, including crawl spaces walls, flat roofs, and sloping walls which are parallel to the roof surface | 0.20 |

Gates or trapdoors to outdoor areas or unheated spaces, and glass walls and windows facing rooms heated to higher temperatures (where the difference in the ambient temperatures between these rooms is 5 °C or more) | 1.80 |

Domes | 1.40 |

Sun tunnels (or similar structures) | 2.0 |

Building part | Linear thermal transmittance [W/mK] |

Interface between exterior wall and windows or exterior doors, gates, and trapdoors | 0.06 |

Interface between roof assembly and roof lights or domes | 0.20 |

Renovations

In roof renovations, special energy provisions for thermal transmittance in roof assemblies apply. Re-insulation must typically be carried out to the standard required in new builds if this is financially viable and does not involve a risk of moisture-induced damage (BR18, § 274–279).

According to applicable regulations, renovated roof assemblies must therefore be thermally insulated with a U-value of 0.12 W/m2K and there must be a linear thermal transmittance around roof lights and domes of below 0.10 W/mK (BR18, § 279). When renovating buildings, it is possible to satisfy the provisions in the form of an energy performance framework using the renovation classes for existing buildings (BR18, § 280–282) as an alternative to these component requirements.

The specific provisions for energy saving measures in roof renovation depend on whether the renovation is classed as repair, conversion, or replacement.

Table 10. Minimum requirements for thermal insulation (U-value) and thermal bridges in interfaces (linear thermal transmittance) for building parts used in roofs (BR18, § 279). In addition to requirements for the loft and roof assembly, requirements for trapdoors leading to unheated spaces (e.g., loft spaces) are also listed.

Building Part | U-value [W/m²K] |

|---|---|

Loft and roof assemblies, including crawl space walls, flat roofs, and sloping walls parallel to the roof | 0.12 |

Gates or trapdoors to outdoor areas or unheated spaces, and glass walls and windows facing heated rooms (where the difference in the ambient temperatures between these rooms is 5 °C or more) | 1.80 |

Domes | 1.40 |

Sun tunnels (or similar structures) | 2.0 |

Building part | Linear thermal transmittance [W/mK] |

Interface between exterior wall and windows or exterior doors, gates, and trapdoors | 0.06 |

Interface between roof assembly and roof lights or domes | 0.10 |

Repairs

Repair involves minor alterations, specifically to less than 50% of the total area. Repairs are not subject to provisions for implementing viable energy savings (e.g., replacing a few roof tiles or repairing flashings around penetrations) (cf. Section 4.0, Ombygninger og udskiftninger af bygningsdele (Conversions and Replacement of Building Parts) in: Bygningsreglementets vejledning om energiforbrug (Guidelines in the Building Regulations on Energy Consumption) (The Danish Transport, Construction and Housing Authority, 2018a)).

Conversions

Conversion describes circumstances in which a building part is renovated or altered (e.g., when the roof covering is replaced). For conversions or major repairs (i.e., when the work involves more than 50% of the building part and it is deemed viable), the roof must be re-insulated, if prudent to do so (i.e. if it is feasible and will not involve any risk of moisture-induced damage). According to the Danish Transport, Construction and Housing Authority, 2018a), examples of tasks requiring viable insulation include:

- New tiled roofs (or similar structures)

- New roof coverings (new top-layer bituminous felt or roofing foil on existing roofs)

Viable energy savings relative to re-insulation, for example, means that the annual energy savings multiplied by lifespan, divided by the investment should be larger than 1.33 (BR18, § 274).

The investment is the extra cost incurred for wages and materials (e.g., when extending rafters, installing new fascia, new flashings, raising roof lights and dormers, added brickwork, installing vapour barriers and thermal insulation resulting from increased thermal insulation thickness).

No re-insulation is required if it would pose a risk of moisture-induced damage (BR18, § 274).

If it is not viable to re-insulate to comply with current insulation requirements (a U-value of 0.12 W/m2K) re-insulation using smaller thicknesses must be used providing this is viable. A calculation to assess the viability of further re-insulation is based on an assembly where the additional insulation in the hollow space has already been performed (cf. Section 4.0 in the Bygningsreglementets vejledning om energiforbrug (Guidelines in the Building Regulations on Energy Consumption) (the Danish Transport, Construction and Housing Authority, 2018a)).

Typically, it would be viable to re-insulate accessible horizontal loft spaces in lattice-trussed roof assemblies, while it will not always be viable to re-insulate when renovating couple roof assemblies. Information on energy provisions and examples of solutions that would normally be viable are outlined in the Bygningsreglementets vejledning om ofte rentable konstruktioner (Guidelines in the Building Regulations on Assemblies Likely to be Financially Viable) (the Danish Transport, Construction and Housing Authority, 2019).

Replacement

Replacement is the term used when building parts are replaced. This may be an entire roof assembly, inclusive of roof covering, rafters, thermal insulation, and loft (cf. Section 4.0 of the Bygningsreglementets vejledning om energiforbrug (Guidelines in the Building Regulations on Energy Consumption) (the Danish Transport, Construction and Housing Authority, 2018a)). For replacement work, the U-value of the assembly must be max. 0.12 W/m2K and the linear thermal transmittance around skylights and roof lights must be max. 0.10 W/mK (BR18, § 279). When replacing or adding dormers, for example, it may not always be possible to meet applicable requirements for components, but this can be compensated for by increasing thermal insulation elsewhere, for example.

Issues concerning airtightness in connection with renovation are outlined in Section 8, Roof Renovation.

2.4.2 Thermal Insulation of Roofs

Various types of thermal insulation can be used for thermal insulation, including:

- Mineral wool produced from glass or rock

- Cellular plastic

- Organic materials (e.g., hemp, flax, paper, or wood fibre)

- Foamed glass

A material’s thermal insulation capacity is indicated by their thermal conductivity or lambda value (λ-value). The thermal conductivity of thermal insulation materials is determined through testing according to a series of coordinated European product standards. The lower the lambda value of a given material the better the insulation capacity.

Cellular plastic thermal insulation material includes polyisocyanurate (PIR), polyurethane (PUR), polystyrene (EPS and XPS), and phenolic foam. Cellular plastic insulation may have lambda values as low as approx. 0.020 W/mK. The lambda values of mineral wool insulation typically range between 0.030 and 0.040 W/mK while the lambda values of organic thermal insulation materials made of paper or cellulose fibres typically range from 0.035 to 0.045 W/mK.

In timber assemblies where the thermal insulation is installed between the timber elements, soft mineral wool insulation mats or blown-in loose-fill thermal insulation (of mineral wool or paper for example) is used. Adjusting inflexible rigid-foam insulation boards such as PIR, PUR, EPS, or XPS is difficult, because the insulation is incapable of absorbing the tolerances which exist in timber assemblies.

For warm roofs, a rigid walk-proof thermal mineral wool, foamed glass, polystyrene, PIR, or PUR is used.

Which specific type of thermal insulation to use in a given roof assembly depends on the fire safety regulations which apply to the building in question (see Section 2.5, Fire Safety Regulations for Roofs).

2.4.3 Airtightness

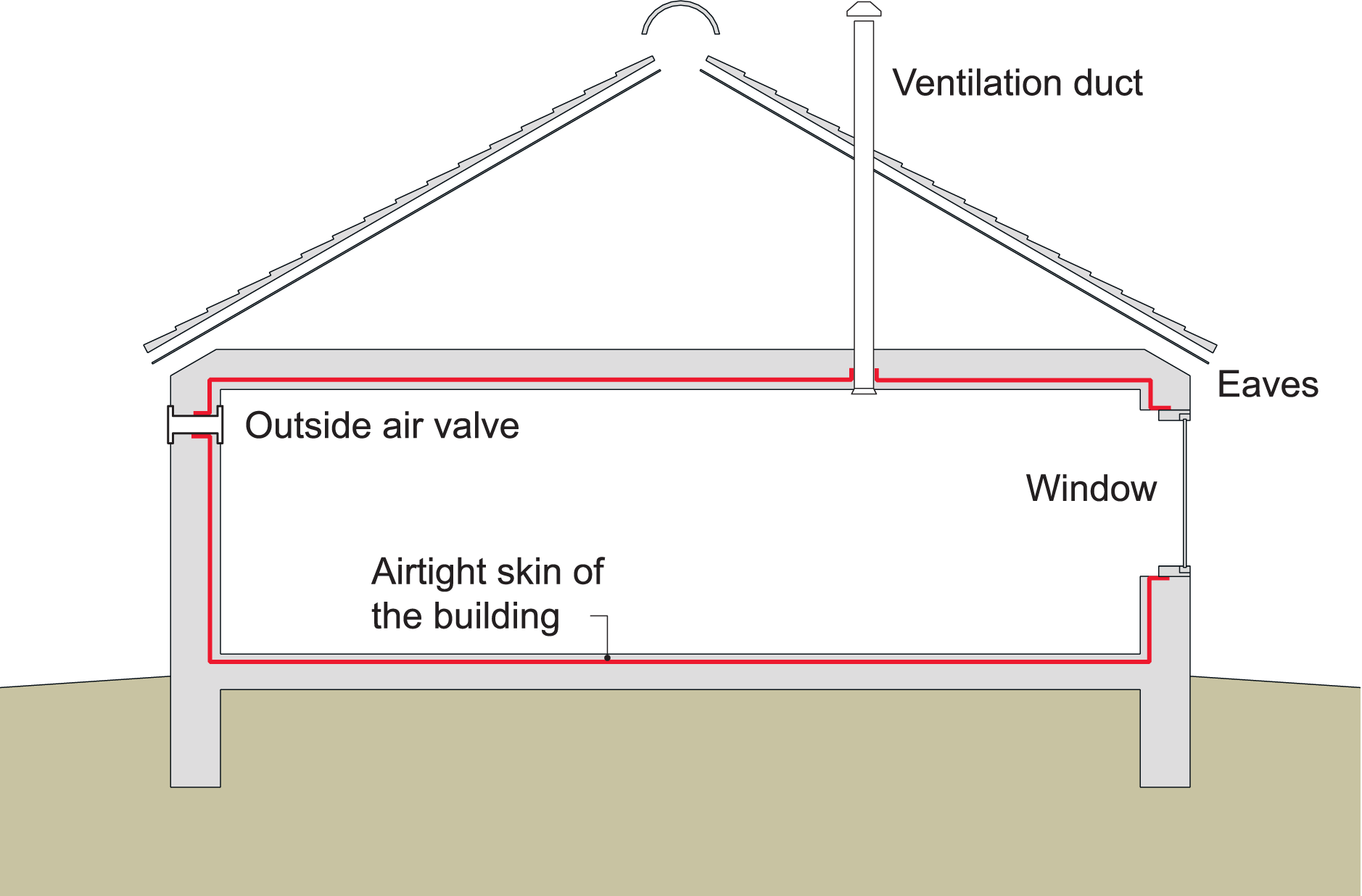

As part of the energy provisions specified in the Building Regulations, there are requirements governing the airtightness of buildings (BR18, § 263). These requirements were introduced to avoid draft problems and unnecessary heat loss due to air leakage in the building envelope. A tight building envelope can be achieved by ensuring a continuous airtight enclosure (see Figure 22). The airtight enclosure is often achieved with a vapour barrier, which (in addition to being vapour-impermeable) must be installed with tight joints, penetrations, and intersections (see Section 2.1, Water and Moisture Tightness).

The provisions in the Building Regulations for airtightness specify a maximum value for airflows through a building envelope at a pressure difference of 50 Pa between the indoor and outdoor environment. Whether or not these requirements are met is documented by testing both positive and negative pressure compared to the outdoor pressure according to DS/EN ISO 9972 (Danish Standards, 2015a). The result is specified as the mean value of these two results.

In new builds, the airflow at a pressure difference of 50 Pa (w50) must be below 1.0 litres/second per m2. The area is calculated as the building’s heated gross area. For buildings with high-ceilinged rooms where the surface of the building envelope divided by the floor area is greater than 3, the airflow must not exceed 0.3 litres/second per m2 (BR18, § 263).

For the optional low-energy class (BR18, § 481), the airflow is required to be below 0.7 litres/second per m2 of the floor area. For buildings with high-ceilinged rooms where the surface of the building envelope divided by the floor area is greater than 3, the flow rate through air leakages must not exceed 0.21 litres/second per m2 of the building envelope.

Issues concerning airtightness relative to renovation are outlined in Section 8, Roof Renovation.

Figure 22. To ensure airtightness, the airtight enclosure (indicated by a red line) must be continuous and tight (i.e., there must be no possibility of cold outside air migrating into the building nor warm and moist air migrating into the structures).

Leakages

Requirements for airtightness also impact significantly on the moisture conditions in the roof assembly, since effective tightness inside the roof assembly reduces the risk of airflow into the assembly and hence of moisture-induced damage.

Even buildings which meet airtightness requirements will always have minor air leakages, which means that the building will never be absolutely airtight. The leakages should be evenly distributed, avoiding a predominance of air leakages in the roof assembly, which may lead to moisture issues.

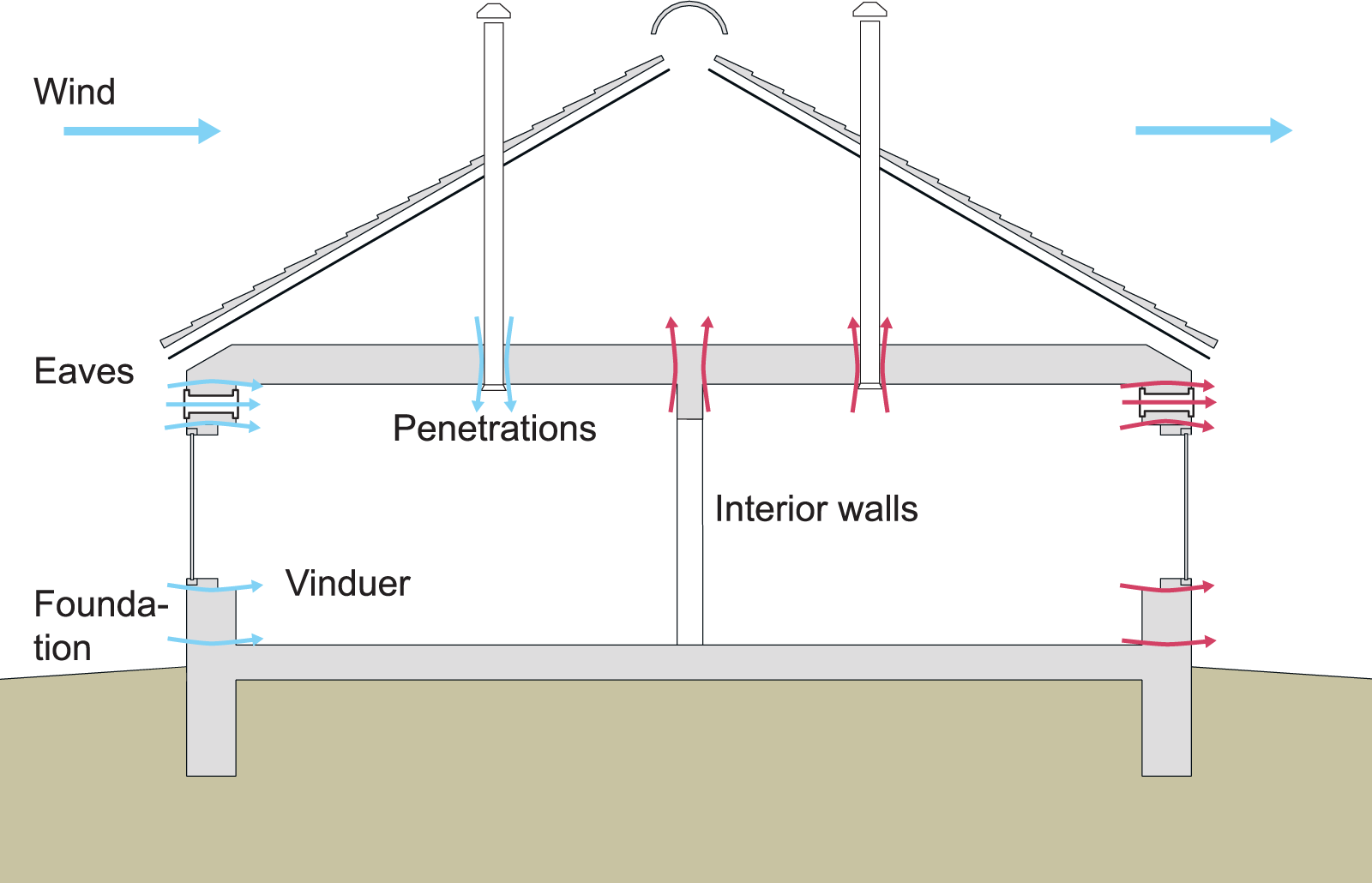

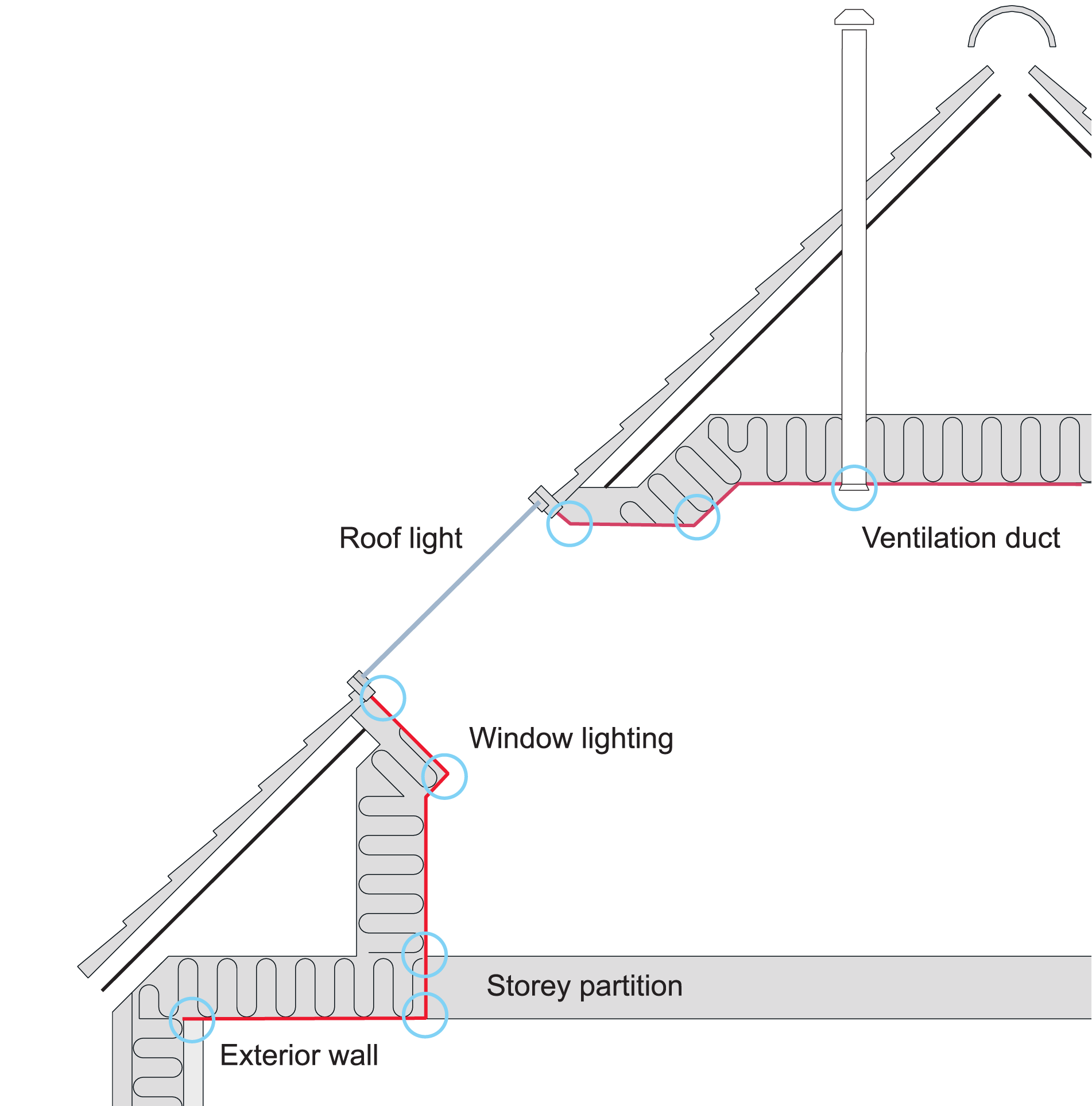

The design and location of the airtight enclosure is of major significance for the overall airtightness, especially the joints between the individual parts of the airtight enclosure (e.g., between vapour barriers in the walls and roof as well as penetrations (see Figure 23)).

The location of the airtight enclosure and the airtightness of all details should therefore be an integral part of the design from the early stages. To achieve optimal airtightness, details should be designed to be buildable. Joints and penetrations in the vapour barrier must always be made on a firm underlay, for example, one made of plywood (see Section 2.1.2, Vapour Barriers in Roofs).

Figure 23. In the past, many new buildings were relatively draughty. The figure shows wind action and airflow through a building, with draft problems in the windward side (blue arrows indicate cold air streaming into the building) and heat loss through random air leakage paths in the building envelope in the leeward side (red arrows indicate leakages where warm air flows out of the building or into the roof assembly).

Materials Used for the Airtight Enclosure

The airtight enclosure normally consists of a variety of different materials/structures with, for example, an inner leaf of aerated concrete and PE foil in the roof. Consequently, airtightness must be achieved partly through the materials themselves and partly via the joints made between different materials or building parts.

Vapor barrier materials for making airtight enclosures in roofs include the following:

- Foil vapour barriers can normally be regarded as airtight in themselves. In the case of thick foils (e.g., 0.2 mm PE foil) the rigidity may inhibit tight corner details. To ensure airtightness, special tapes, foil adhesives, pre-fabricated sleeves, etc., designed for use with a given foil should be used (these are referred to as systems solutions).

- Vapour barriers in warm roofs are often used as roofing membranes of bituminous felt or roofing foil, fixed either to firm wooden decking or concrete decking or laid loosely (with tight joints) on an underlay of thermal insulation material.

- Sheet materials such as plasterboard and plywood are usually airtight while Oriented Strand Board (OSB) materials are only considered airtight if sheets specifically designed for airtightness are used. Joint interfaces must be carefully and durably sealed.

Vented Roofs

In vented roofs, the airtight enclosure will usually be on the inside of the roof assembly (e.g., constructed by means of a vapour barrier or interior cladding) (see Figure 24). The airtightness of the roofing underlayment is not considered. Specific requirements apply to the correct choice of material as well as to design and construction details.

Please consult Bygningers lufttæthed – tæthedskrav, bygningsudformning og måling (Airtightness in Buildings – Tightness Standards, Building Design, and Measurement) (Byg-Erfa, 2013) and www.membranerfa.dk.

Figure 24. The airtight enclosure in a vented roof assembly (red line in cross section of collar roof) (e.g., using a vapour barrier) must be continuous to ensure an airtight roof assembly. The vapour barrier in the roof assembly must be made airtight at the exterior wall interfaces and roof lights (if there are any) to ensure a continuously airtight enclosure. Joints and intersections (blue circles) (e.g., at windows, roof lights, and ventilation ducts) require careful planning, design, and construction. Joints between, and penetrations in, vapour barriers must be executed on a firm underlay to ensure durable solutions with a high level of airtightness.

Warm Roofs

Warm roofs are chiefly constructed with a tight vapour barrier and a tight roof covering consisting of a roofing membrane. Here, too, specific requirements apply to the correct choice of materials, design, and execution of details.

Warm roofs are not vented between vapour barrier and roof covering, so the roof covering may therefore contribute to meeting the requirements regarding airtightness.

However, the roof covering cannot always be relied on to be airtight at the eaves, etc., which means that the roof assembly could be subject to pressure compensation. Furthermore, strong winds may cause movement in the roof covering (negative pressure above the roof), leading to negative pressure in the roof assembly between the vapour barrier and the roof covering. This could lead to indoor air being drawn in if there are leakages in the vapour barrier. It is therefore vital to install the vapour barrier very carefully to avoid moisture absorption.

In warm roofs with a supporting structure of profiled steel sheets where the vapour barrier is usually placed 50 mm into the thermal insulation (for reasons of fire safety), airtightness must be secured at this level.

2.5 Fire Safety Regulations for Roofs

Fire may adversely affect roofs from both the inside and the outside. Chapter 5 in the Building Regulations, Fire, contains provisions for roofing materials and structures intended to reduce the risk of flame spread on both accounts (BR18, § 82–158).

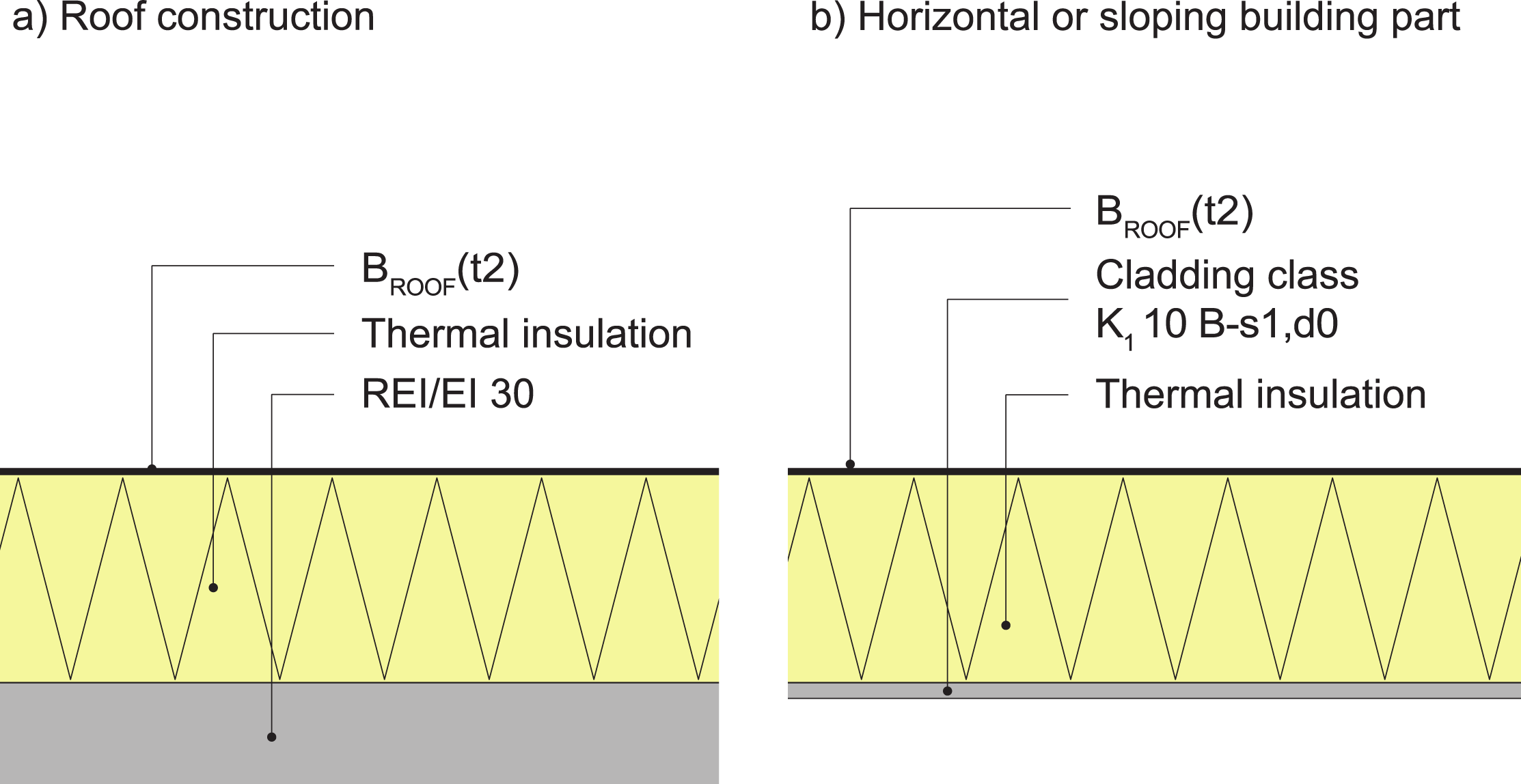

According to BR18, building parts must be classified according to categories of use, risk classes, and fire classes.