8 ROOF RENOVATION

Roof renovation includes all work to repair damage or improve existing conditions relating to the roof structure. Renovation could include re-insulating an existing loft space or replacing the roof covering.

8.1 Building Regulations – Provisions for Renovations

For major renovations, the roof will normally be subject to Building Regulations provisions concerning either re-insulating the roof to current standards or for it to be viable and to avoid moisture-induced damage (BR18, § 274).

The specific provisions for energy conservation relative to roof renovation depend on whether the renovation comprises repair, conversion, or replacement (see Section 2.4.1, Building Regulations – Energy Provisions).

Re-insulation will not only reduce energy consumption, but also add comfort, so re-insulation should always be considered, even if it might not be viable.

When replacing roof coverings, energy saving provisions will often lead to extensive work where it may be necessary to realign rafters, add firring to the assembly (upwards or downwards) to make space for thermal insulation, to install a vapour barrier, or to install a roofing underlayment.

8.2 Roof Renovation Design

Renovation work generally needs to be designed and executed according to the same guidelines which apply to new builds. However, renovation projects are likely to be more complex than new builds, because, for one thing, one is bound by the original roof design. In renovation projects, awkward details must be carefully planned and they must be feasible.

Prior to a renovation, careful consideration must be given to whether the roof's geometry (slope, overhang, etc.) needs to be changed and whether a new type of roof covering should be installed. Before starting renovation work, a surveyor’s report should be issued for the roof in question.

The surveyor’s report should include:

- Existing roof covering (type, weight, condition)

- An assessment of the load-bearing capacity of rafters and the roof structure generally. If a heavier type of roof covering is installed, this could necessitate an increase in load-bearing capacity. If a lighter type is installed, the anchorage must be capable of absorbing wind force.

- Whether the existing roof construction is satisfactory, or whether there a need for reinforcement or repair of existing assemblies. For load-bearing capacity and stability see SBi Guidelines 254, Small Houses – Strength and Stability (Cornelius, 2015), TRÆ 58, Træspær 2 – Valg, opstilling og afstivning (Timber Rafters 2 – Choice, Installation, and Bracing) (Træinformation, 2009b), TRÆ 60, Træplader (Timber Sheets)(Træinformation, 2012), Træ 73, Tagkonstruktioner med store spær (Roof Assemblies Using Large-Scale Rafters) (Træinformation, 2017), Betonelementer (Concrete Slabs) (Betonelement-Foreningen, 1991), or Stålkonstruktioner efter DS/EN 1993 (Steel Constructions According To DS/EN 1993) (Bonnerup, Jensen & Plum, 2015).

- An assessment of whether the assembly is airtight. (There should be no risk of convection of moist indoor air.)

- An assessment of whether a vapour barrier has been installed. If one has been installed, information about its condition and the tightness of its installation should be included.

- Whether there are visible signs of mould fungus or moisture-induced damage.

- An assessment of whether the blower-door test should be performed to check or evaluate the tightness of the envelope (see e.g., Lufttæthed I ældre bygninger – efter renovering og fornyelse (Airtightness in Old Buildings – After Renovation and Improvements)) (Byg-Erfa, 2016a).

- Whether there is enough space in the assembly for re-insulation and whether this is viable?

- An assessment of whether the insulation should be changed. If it should be changed, whether flammable thermal insulation can be protected.

- Whether parts of the existing thermal insulation should be changed (e.g., from sheet-based to loose-fill insulation). If they should, steps must be taken to ensure that its contribution (if any) to the fire resistance of the storey partition is not reduced.

- An assessment of storey partitions, inserts, and pugging. Storey partitions with inserts and pugging must not be damaged and the flooring must be retained so as not to compromise fire resistance. If the story partition is changed, the level of fire resistance must be re-established in other ways.

- An assessment of whether the assembly should be lined on the inside or the outside to improve thermal insulation capacity, and whether this is viable.

- Whether supplementary thermal insulation or structural changes pose a risk of moisture-induced damage.

- Whether there are any leaks (e.g., near trapdoors or penetrations) which need repairing.

For information and solutions on ensuring the fire safety of roofs in connection with renovations, please see Gode & brandsikre tage – Vejledning om brandsikring ved renovering af tage (Sound and Fire-Safe Roofs – Guidelines on Fire Safety for Roof Renovation) (DBI Fire and Security, 2014) and TRÆ 71, Brandsikre bygningsdele (Fire-Proof Building Parts) (Træinformation, 2015).

Issues concerning the conversion of loft spaces to dwellings are outlined in SBi Guidelines 255, Etablering af tagboliger (Constructing Loft Dwellings) (de Place Hansen, 2009a) and SBi Guidelines 256, Tagboliger – byggeteknik (Loft Dwellings – Construction Techniques) (de Place Hansen, 2009b).

8.2.1 Ventilation and Roof Renovation

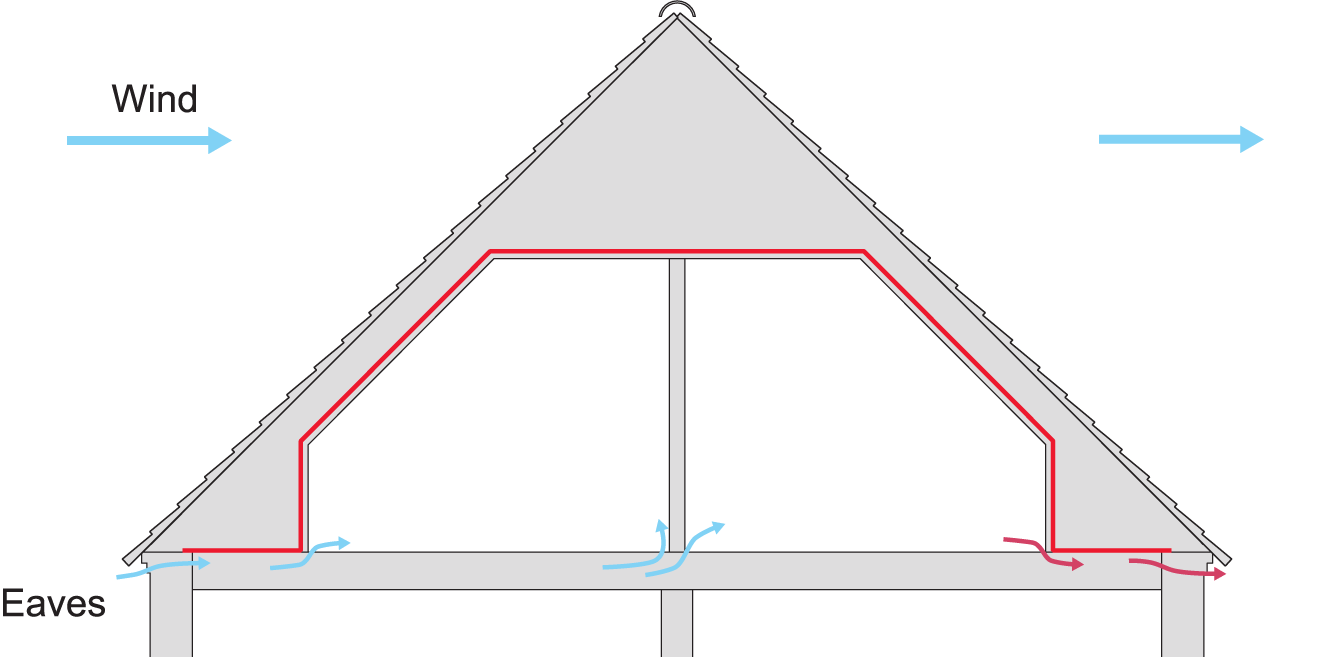

When renovating and re-insulating vented roofs, steps must be taken to ensure that the loft space is adequately vented after the renovation work has been completed. Ventilation guidelines are the same as for new roofs (see Section 2.3, Roof Ventilation).

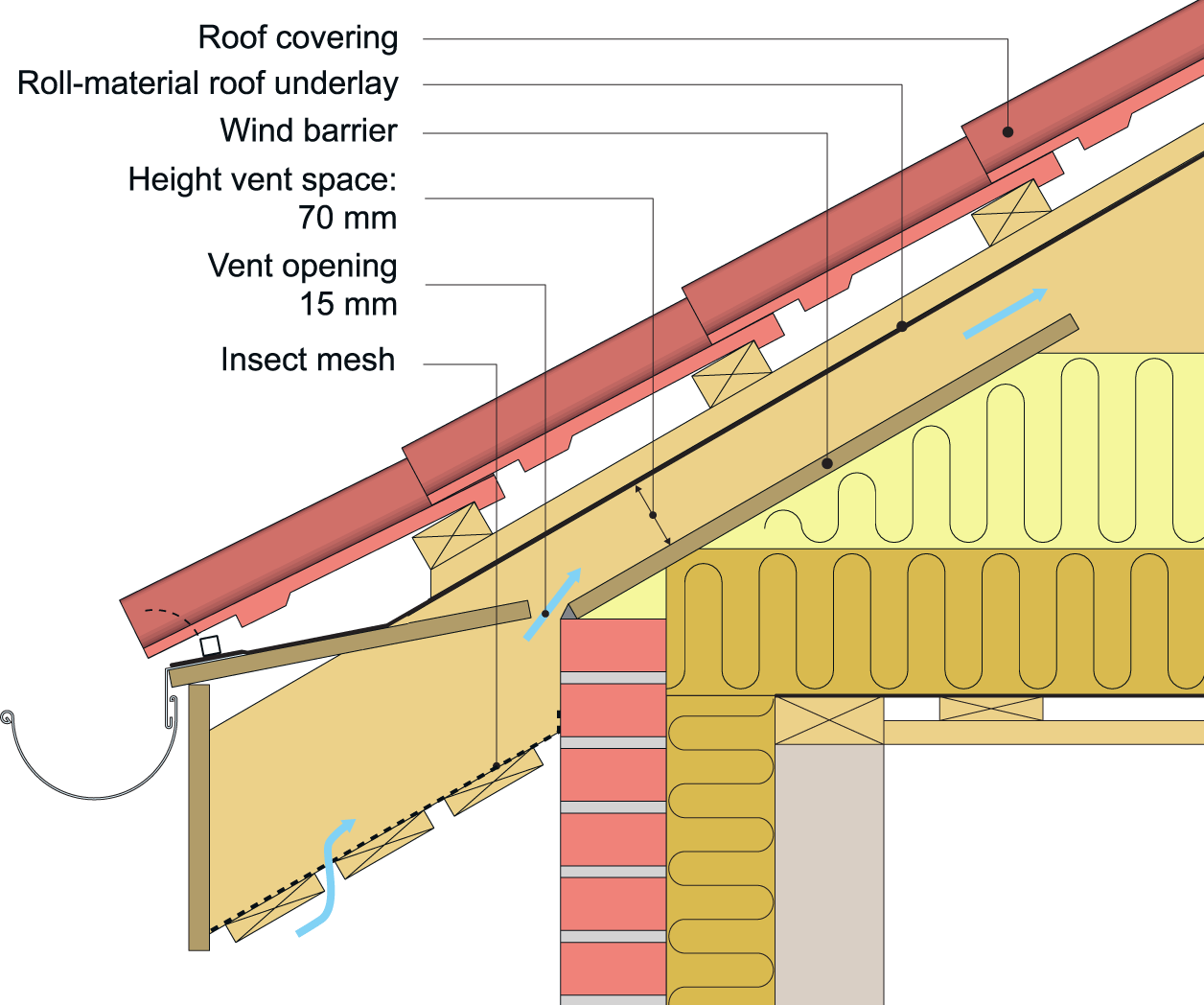

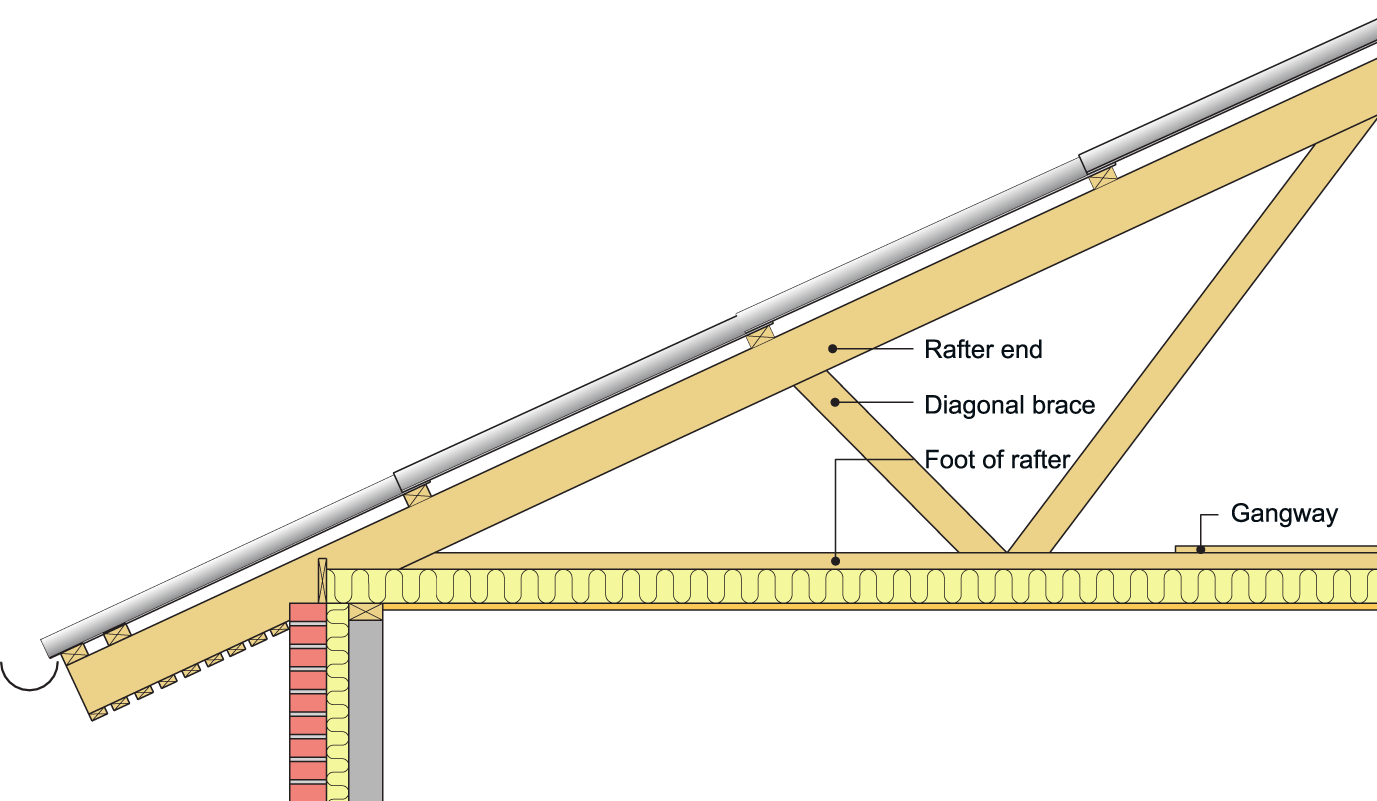

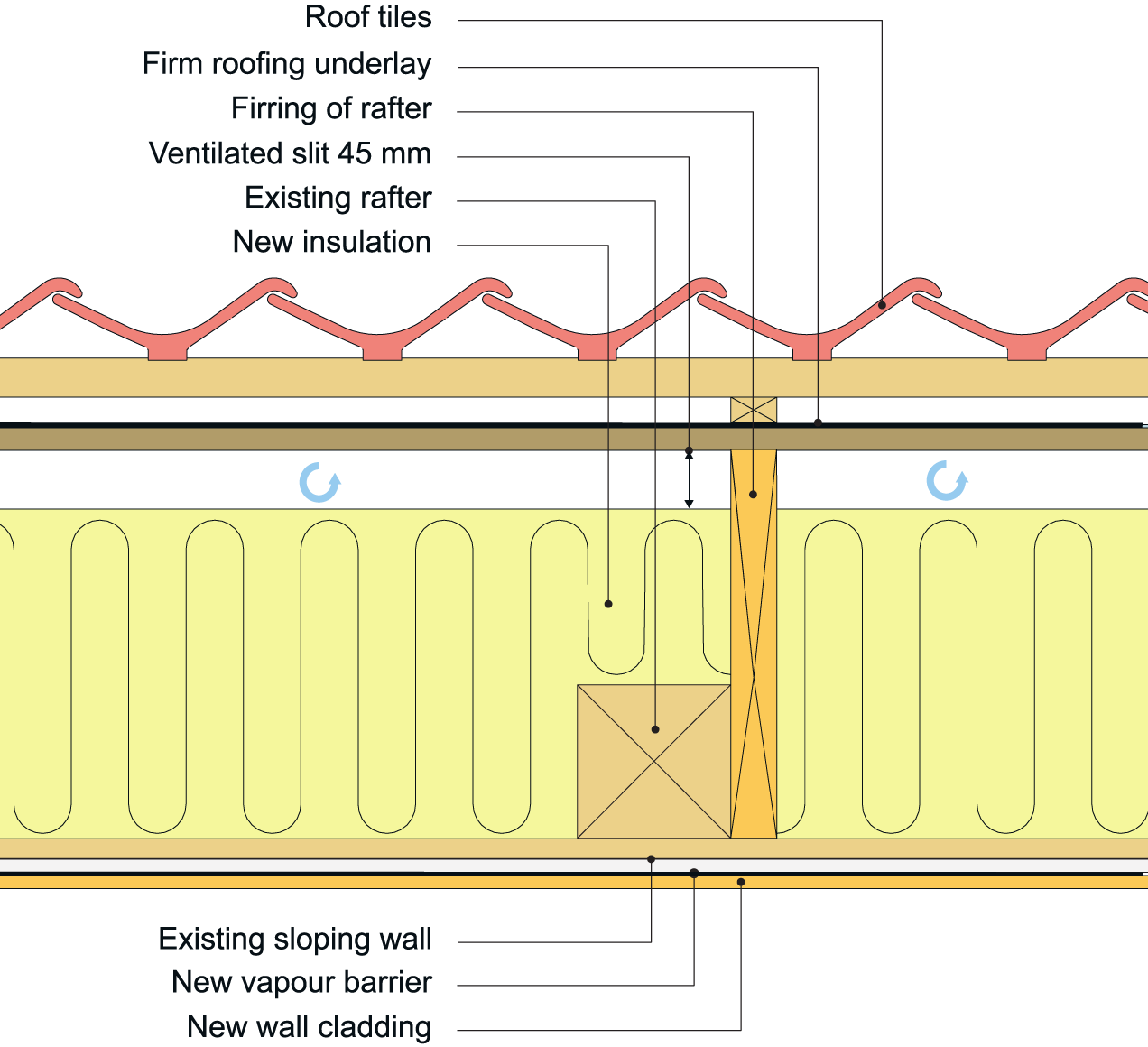

For pitched roofs, the eaves area is particularly critical when re-insulating. The best method to prevent blocking the ventilation is to install a wind barrier sheet or wind stop (e.g., of plywood or rigid-foam insulation) between the rafters. The spacing between roofing underlayment and wind barrier sheet must equal the height of vent spaces (i.e., min. 45 mm for firm underlayment and 70 mm for roofing underlayment of roll material or wood-fibre sheets) (see 2.3.2, General Ventilation Guidelines, and for further information, see Section 3.4, Details – Roofing Underlayment for Eaves Details). If the eaves are designed to be fire-safe and the vent space, therefore, is considered an opening, this must be 30 mm wide (including fitted insect net) (see Figure 231). When designing eaves for buildings with requirements to prevent flame-spread via the eaves (e.g., multi-storey residential buildings), the vent opening must be min. 300 mm long and max. 30 mm high (see Figures 47 and 48) (DBI Fire and Security, 2007).

Figure 231. Securing the ventilation when re-insulating around the foot of rafters in detached single-family pitched-roof dwellings can be achieved by installing a plywood wind barrier (shown here) or rigid-foam insulation between rafters. The spacing between roofing underlayment and wind barrier must equal the height of vent spaces (i.e., min. 45 mm for firm underlayment and 70 mm for roll-material underlayment (shown here) or wood-fibre sheet). The wind barrier can also help ensure that no cold air will penetrate underneath the insulation. If a solution is preferred which also reduces the risk of flame-spread to the roof assembly, a vent opening must be installed between two sheets (see Figure 47). Here, an insect mesh has been laid across the soffit boards. Therefore, the vent opening need only be max. 15 mm.

Flat cold roofs from the 1960s and 70s, will typically slope slightly towards inside outlets. It is a good idea to renovate such buildings with a new 1:20 or 1:40 slope towards outside gutters. This means that the roof edge need not be increased to the same extent as for an inside outlet. Such roofs can be renovated with outside thermal insulation and be converted to a warm roof (see Section 1.3.2, Warm Roofs). Alternatively, firring can be added to the rafters so that the roof can is thermally insulated whilst remaining a vented roof (see Section 1.3.1, Cold Roofs).

8.2.2 Roofing Underlayment and Roof Renovation

When renovating pitched roofs, it will often be necessary to install roofing underlayment, especially when planning to utilise the top floor.

Prior to installing roofing underlayment, the rafters must be checked for any damage and may need realigning. To allow for the nailing of spacer bars and battens, firring is added using planks min. 45 mm thick which are usually fixed to the side of rafters. If firring is used on top of rafters, care must be taken that the pull-out strength of nails or screws is sufficient to absorb wind force on the roof.

Examples of roofing underlayment and general guidelines for roofing underlayment are outlined in Section 3, Roofing Underlayment.

8.2.3 Vapour Barriers and Roof Renovation

When renovating roofs, a continuous airtight enclosure must be established in conjunction with the remaining building parts in the climate envelope to prevent convection of moist indoor air into the roof assembly. The airtight enclosure consists of airtight materials (e.g., a vapour barrier or an intact plaster ceiling). Please note that plaster ceilings which are not intact are incapable of securing airtightness.

When renovating old leaky roof assemblies, a new airtight enclosure must be established. This is typically achieved with a vapour barrier.

Installing vapour barriers in a roof renovation must be carried out according to the same guidelines as for similar new structures. However, it cannot be expected that vapour barriers installed during renovation will meet the same requirements for airtightness that exists in new builds (see Section 2.4.3, Airtightness).

Please note that plaster ceilings can be considered airtight if they are intact (i.e., they are free of cracks or holes). On the other hand, they cannot be considered vapour-impermeable (vapour proof).

In structures with intact plaster ceilings, re-insulation is carried out using flexible insulation (e.g., sheets or loose-fill made of mineral wool or cellulose-based fibre materials) without installing a vapour barrier. It is vital that there are no spaces between the insulation and the rafters, etc. as this might allow moist indoor air to escape into the assembly. The insulation thickness is unimportant. The following are preconditions of the renovation:

- Airtightness of the roof assembly must be adequate. This can be checked by examining the roof assembly before the re-insulation is commenced. If there are no visible signs of moisture absorption or black mould, the airtightness can be considered adequate.

- Relevant structural parts are accessible for inspection (i.e., unutilised loft spaces, apexes, crawl spaces, etc.).

- Ventilation conditions in the loft space, after re-insulation, adhere to applicable guidelines for ventilation of the specific type of roof assembly.

- Airtightness of the roof assembly is not reduced (e.g., by perforations for spotlights, the dismantling of sheets, or other structural changes.

If there is any doubt about whether the moisture conditions are satisfactory (e.g., if there is any visible black mould), a moisture calculation can be performed or mould samples taken in areas where the risk of moisture or mould growth is estimated to be the greatest (e.g., near valleys, hips, and penetrations).

Most vapour barriers (foils) will (even when relatively thin) be sufficiently vapour proof if they are intact. However, they must be handled with care, as they are easily damaged. Thick vapour barriers are more robust, but can be difficult to handle, because they are more rigid. It is important, therefore, to select vapour barriers suited to the particular job. General guidelines concerning vapour barriers are outlined in Section 2.1.2, Vapour Barriers in Roofs.

If the roof assembly already has a vapour barrier, it should be checked and any leaks should be repaired. It is especially important to check that joints are made using adequate overlaps or are bonded, that the vapour barrier has a tight finish with all adjoining building parts and penetrations, and that the vapour barrier itself has not disintegrated. Special checks should be made to ascertain whether there are any leakages around power installations in the loft.

If there is any doubt whether the vapour barrier is effective, the best solution is to install a new one.

Alternatively, it may be necessary to evaluate the airtightness of the existing vapour barrier by performing an airtightness test (see Section 8.2, Roof Renovation Design).

8.2.4 Airtightness and Roof Renovation

In a new build, it is a requirement that the airflow, at a pressure difference of 50 Pa (w50), is below 1.0 litre/second per m2 (BR18, § 263). Renovations are not subject to specific requirements, but it is advisable to focus on improving the airtightness during renovation. Improving the airtightness in the climate envelope will reduce energy consumption, resulting in a much-improved indoor climate with far fewer draught problems, because there will be no unchecked airflows through random leakages.

It is possible to specify requirements for the quality of the building parts being renovated, but not normally for the entire building. It is important to be realistic and to adjust expectations for levels of airtightness so that the desired level can be achieved in practice. The achievable airtightness is largely dependent on the extent of the renovation. When renovating, the building parts subject to renovation should, at a minimum, be handled according to best construction practice and one should aim for the end product to be better or tighter than the original. If no specific requirements for airtightness are stated in the project, the work must be performed according to best practice in terms of craftmanship and the renovation must meet the agreed quality level (e.g., no extensive local leakages).

There will often be several options for ensuring airtightness and a solution should be determined the most reliable and easiest to work with. Strict design and execution requirements must be formulated prior to commencing the renovation.

When improving airtightness, it will often be necessary to improve the ventilation in the building to avoid moisture problems such as condensate on cold surfaces.

Leaktightness Test After Renovation

If only part of a building is being renovated, a leaktightness test (blower-door test) will often be useful to assess the tightness of the renovated part (see Lufttæthed I ældre bygninger – efter renovering og fornyelse (Airtightness in Older Buildings – After Renovation and Replacement)) (Byg-Erfa, 2016a).

Using blower-door equipment, it is possible to eliminate all input from a non-renovated building section with a two-zone test.

If a top floor but not the ground floor is renovated, two vents can be set up to ‘run’ simultaneously. When the pressure on the ground and top floor are identical, there will be no pressure difference above the floor. In this way, all input from the ground floor is eliminated and only measurements from the top floor ventilator are used.

Leakages can also sometimes be pinpointed using a fog machine (see Figure 232). Fog machines can be used for both partial vacuums and excess pressure if a pressure difference is established between the two areas.

Figure 232. Leakages near joints, penetrations, and intersections can sometimes be detected using a fog machine when adding slight excess pressure to the structure during leaktightness testing.

Details

Design and execution of construction details with vapour barriers are vital for the airtightness of the roof assembly after renovation. In roof assemblies, the worst leakages often occur at eaves and gable ends, and at intersections and junctions (e.g., tie beams and crawl-space posts).

To execute the vapour barrier construction details correctly and for them to function, porous and dusty surfaces (e.g., old rafters, beams, and plaster), must be cleaned thoroughly to remove loose dirt and dust. Before fixing the vapour barrier with foil adhesive or vapour barrier tape, the surface must be primed to ensure adhesion. Please note that even minor details such as star shakes in beams intersecting the airtight enclosure can cause draught problems unless the leakages are sealed.

If cold outdoor air can penetrate the roof assembly at the eaves, it can cause draught problems (cold air at high velocity) or cold surfaces in the assembly (see Figure 233).

At junctions around beams at eaves, crawl-space posts, and tie beams, firm decking must be installed on which to mount the vapour barrier to enable the foil adhesive or tape to bond correctly. Certain types of sheeting can, in themselves, function as vapour barriers, but it will usually be necessary to install foil as a supplement. The sheeting can be used as a substrate for the vapour barrier, which is continued down through the joists. Star shakes (e.g., in beams) are sealed as efficiently as possible (e.g., by using a caulking compound) (see Figure 234).

Figure 233. Leakages in the roof assembly will allow cold air to flow into the building, causing draughts (e.g., if the parapet wall or the floor leak near the eaves). Furthermore, warm air can flow out of the building, resulting in increased energy consumption.

Figure 234. Leakages near tie beams intersecting the airtight enclosure can cause draught problems due to high-velocity cold air. Star shakes can be made tight using elastic caulking compound.

Vapour Barrier Near Gable End

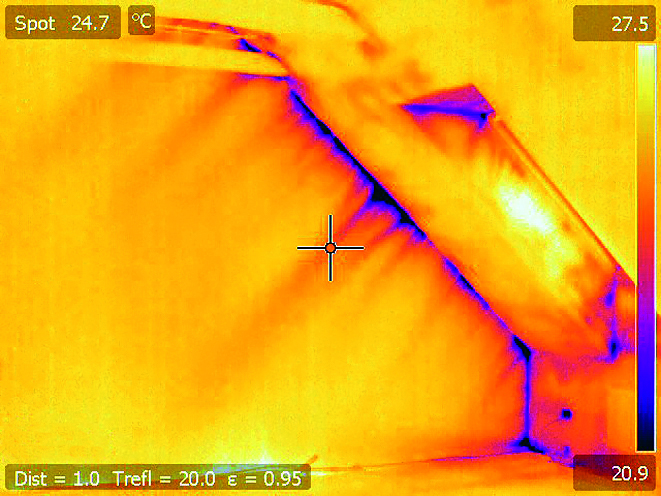

Gable-end rafters are often placed 20–40 mm away from the gable end, allowing air to flow in where the gap between the gable-end wall and rafters is left open (see Figure 235).

In the layer of joists facing the gable end, the brickwork is often untreated and leaks, especially if there is a cavity wall. For gable ends with cavity walls, the tightness around the first beam should be assessed. If the brickwork behind the joists leaks, it may be necessary for a single solution incorporating the whole width of the gable end. For solid gable ends, attention can usually be limited to eave details.

Figure 235. A thermal camera image showing how cold air can flow into a building through a gap between the gable-end wall and the last rafter. The gap is typically 20–40 mm and usually not tightly sealed.

The intersection between a new roof assembly and a vapour barrier facing an existing plaster wall is likely to cause problems.

The tightness can often be improved by connecting the roof vapour barrier (e.g., in crawl-spaces and sloping walls and ceilings) with the gable end. Tape with an integral reinforcement strip can be inserted into a layer of plaster or adhesive and a clamping strip can be used (see Figures 236 and 237).

When using tape with a reinforcement strip, the tape is placed in the transition between the existing structure and the plastered surface, with the reinforcement strip facing the plastered surface. Afterwards, the reinforcement strip is plastered over, thus ensuring a tight joint.

The tightness between gable end and joists in a storey partition at the last rafter (the foot of the rafter) can be improved by sealing the gap with a piece of vapour-barrier foil tied around a compressed joint strip which can then be placed in the gap. When the joint strip expands, it will seal the gap between the gable end and beam (see Figure 238).

Figure 236. A vapour barrier in the roof assembly (shown as a crawl-space wall) can be joined to an exterior wall with a plaster finish using tape with a reinforced strip insert. Afterwards, the reinforcement strip is plastered over, ensuring a sealed joint.

Figure 237. A vapour barrier in the roof assembly (shown as a crawl-space wall) can be joined to a plastered wall surface by bonding the vapour barrier to the surface, which is prepared and primed to ensure adhesion. If possible, the joint should be finished with a wooden strip (or a similar product), so that the joint can be clamped if necessary (see www.efterisolering.sbi.dk) (Kragh et al., 2014).

However, it is rarely possible to fully seal star shakes and unfilled mortar joints in the brickwork using this solution. These will have to be sealed as best as possible given the prevailing conditions.

Ensuring that the vapour barrier fits tightly to the exterior wall at the eaves can be difficult, especially in low-slope roofs. Given that wooden beams are regarded as sufficiently vapour-impermeable, it is sometimes possible to fix the vapour barrier to the wall plate to ensure a tight joint. If possible, the joint should be further secured by both bonding and clamping the vapour barrier. At the eaves, the work will be easier if the roof covering is removed (or, if it is being replaced, for this work to be performed before it is re-installed).

Figure 238 An example of how to seal an existing brick gable-end wall and a beam. It is sealed by placing a piece of compressed joint strip wrapped in plastic foil in the joint. When the joint strip expands, the joint will be sealed. The gap can also be sealed by pressing material further into the gap (www.efterisolering.sbi.dk) (Kragh et al., 2014).

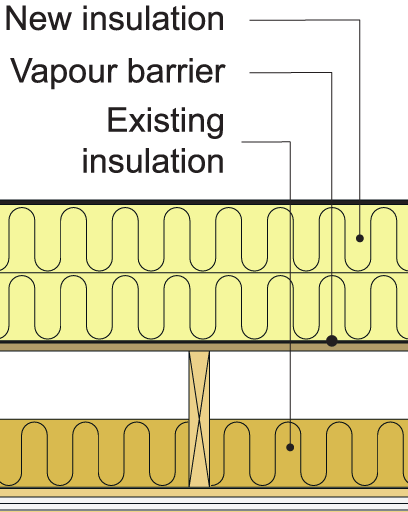

Vapour Barrier in a Ceiling, Installed from Below

If no vapour barrier exists or if the existing vapour barrier is not close-fitting and intact, a new vapour barrier must be installed, which must extend max. 1/3 inside the thermal insulation (measured from the warm side). The simplest and cheapest solution will often be to install a vapour barrier on top of the underlying ceiling and fix it to the adjoining walls. The advantage of this method is that the vapour barrier can often be carried, unbroken, from wall to wall as opposed to installing it from above where the vapour barrier must be broken at the rafters.

Installation from below may require interfering with stucco or power installations for the purpose of establishing a plane underlay for the vapour barrier. In some cases, the existing ceiling cladding will need to come down (e.g., panelled ceilings, and cupboards removed before installing a new vapour barrier.

In terms of occupational health and safety, it is preferable to install the vapour barrier from below rather than form above. Room height permitting, it can be an advantage to install new ceiling cladding on lathing or battens installed below the original ceiling. This allows power installations to be mounted in the ceiling without having to penetrate the vapour barrier.

There is a risk of leakages by the interior walls, but this will normally be of minor importance if the wall surfaces are intact (e.g., plastered or wallpapered).

It is unnecessary to remove an existing vapour barrier in the ceiling structure if it is installed max. 1/3 inside the finished insulation layer measured from the warm side (see Section 8.3.3, Re-Insulating Vented Loft Spaces).

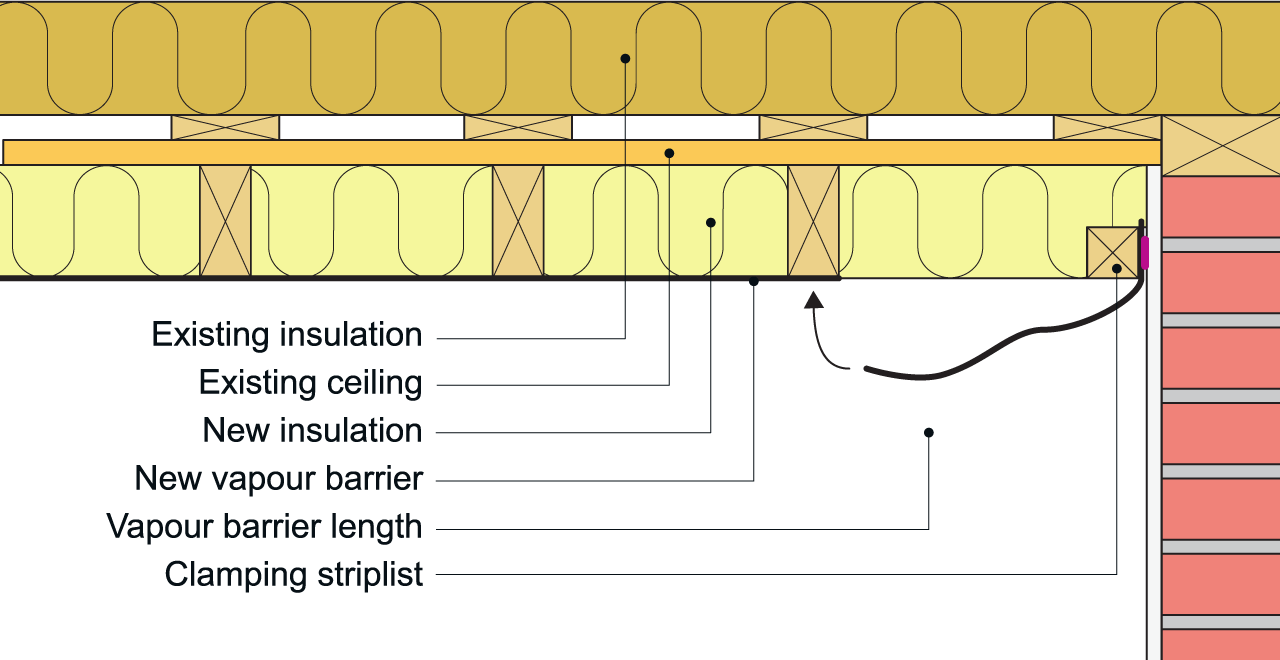

Vapour Barrier in a Ceiling Installed from Above

Rafters are considered sufficiently tight to be included in the vapour barrier. It will therefore sometimes be possible to install a new vapour barrier between rafter feet from the loft space above. However, installation from above will normally require extensive adaptations to ensure tightness which will translate to adverse working conditions. Therefore, this should be avoided as far as possible. Careful execution is required, particularly for details around rafters, intersections of ducts, and power cables. Storey partitions with inserts and pugging must not be damaged and the flooring must be retained so as not to compromise fire resistance. If the story partition is changed, the level of fire resistance must be re-established in other ways.

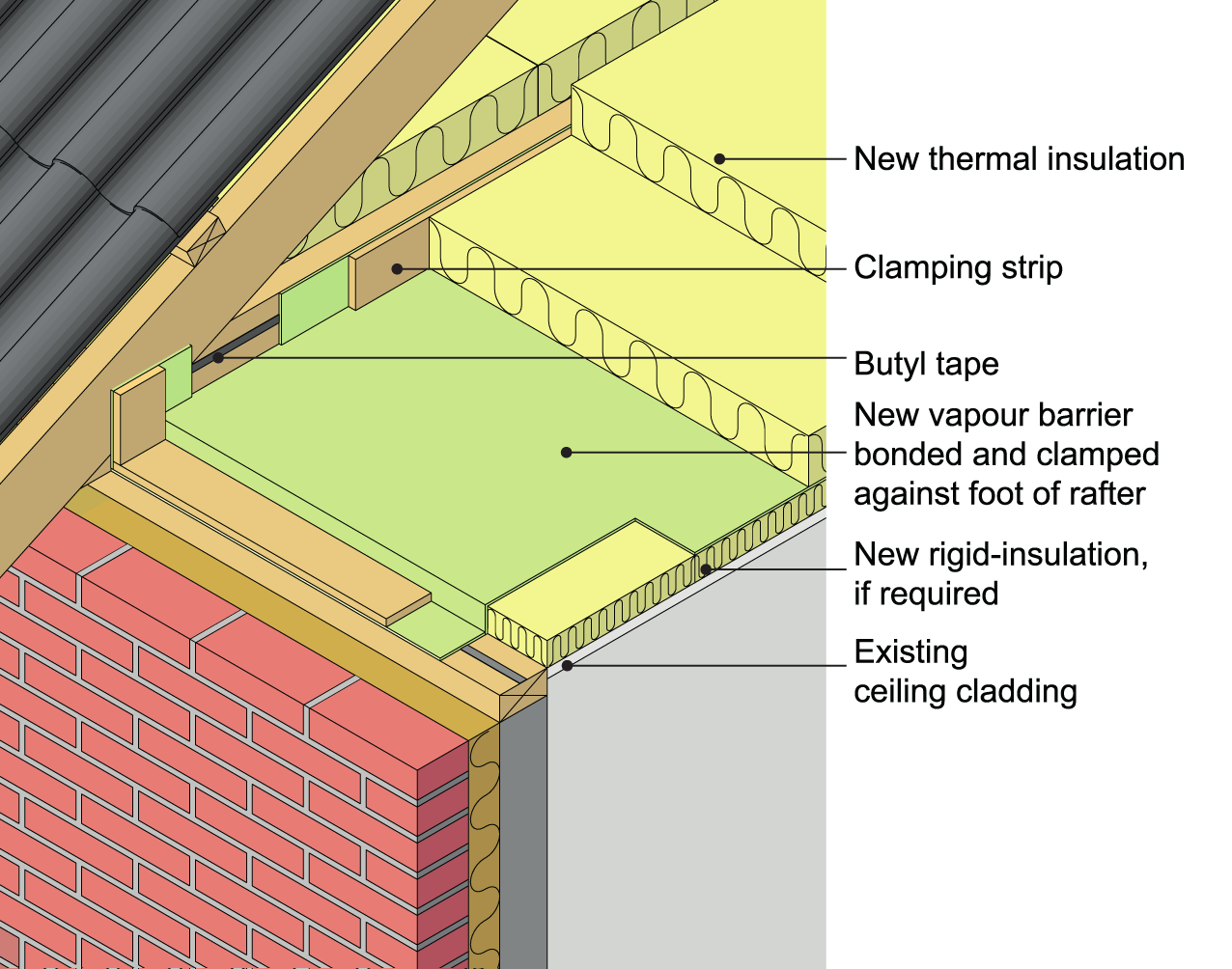

Vapour barriers are installed from above according to the following guidelines:

- If necessary, the existing thermal insulation is removed.

- If there is a risk of damaging the vapour barrier due to nails and other protrusions, a thin layer of rigid-foam thermal insulation can be laid (min. material class D-s2,d2 [class B material]) as a substrate. In dwellings, the thickness must be max. 1/3 of the overall insulation thickness. Typically, 25- or 50-mm thick insulation is used.

- The vapour barrier is laid in lengths between rafter feet.

- Vapour barrier lengths are bent at least 50 mm upwards along the sides of rafter feet. They are fixed carefully and as airtight as possible (e.g., using butyl tape).

- The joint should be further secured with a clamping strip. The remaining thermal insulation is placed on top of the vapour barrier.

Figure 239 shows an example installation of a vapour barrier between rafter feet from above in a crawl space.

Figure 240 shows an example installation of a vapour barrier between rafter feet from above in a vented loft space.

Figure 239. An example of a vapour barrier installation against rafter feet at a cold crawl space. Installing a vapour barrier from above results in poor working conditions and requires time and care when adapting the vapour barrier. The vapour barrier is laid on top of a thin layer of rigid-foam thermal insulation atop lathing in the ceiling. The vapour barrier must be fitted tightly to the wall plate, beams, and plywood divider inserted between crawl-space posts (see Figure 252) (www.efterisolering.sbi.dk) (Kragh et al., 2014).

Figure 240. A schematic showing the installation of a vapour barrier and re-insulation from above in a vented loft space. A vapour barrier is installed between rafter feet. Rafter feet are themselves considered tight, which is why a vapour barrier is only needed between the rafter feet. A thin layer of rigid-foam insulation may be laid at the bottom to absorb unevenness and protect from pointed nails (and similar protrusions) from the existing ceiling. The vapour barrier is continued min. 50 mm up the sides of rafters and fixed (e.g., with butyl tape) and subsequently clamped with a clamping strip (Møller, 2012).

8.3 Re-Insulating Roofs

The options for re-insulating a roof are relative to the roof structure. The following section discusses structural options for re-insulating the most common roof types, including warm roofs, vented loft spaces, vented couple roofs, unvented couple roofs, and crawl spaces.

Guidance to identify the most viable and energy-efficient thermal insulation thickness is outlined in SBi Guidelines 239, Efterisolering af småhuse – energibesparelser og planlægning (Re-insulating Small Houses – Energy Savings and Planning) (Møller, 2012).

8.3.1 Renovating Warm Roofs

Warm roofs are normally renovated by installing a new roof covering which is usually supplemented by mechanically fixed thermal insulation (see Figure 241).

The existing insulation material must be dry or there will be a risk of water from the insulation penetrating the assembly through the holes emerging around the new mechanical fixings. The moisture content of the existing thermal insulation can be examined by scanning the roof using a roof scanner, supplemented with cutting-up and weighing-drying-weighing tests to calibrate the scanning. For small roofs, the thermal insulation can be examined only by cutting.

Small amounts of moisture (i.e., corresponding to max. 0.5 percentage per volume of water in the insulation material) are acceptable (corresponding to 1 kg/m2 for 200 mm insulation). If there are higher quantities, the insulation must be replaced.

Re-insulating on top of existing thermal insulation will always amount to an improvement in moisture. There are therefore no requirements for thermal insulation thickness, except Building Regulations specifications for the U-value of the total structure (see Section 2.4.1 Building Regulations – Energy Provisions).

Old warm roofs do exist that have wood-fibre sheets fitted on top of the mineral wool insulation to distribute weight. In such cases, the additional exterior insulation must comply with the rules in the following Section 8.3.2, Converting Cold Roofs to Warm Roofs. Alternatively, the existing insulation with wood-fibre sheeting must be removed.

Figure 241. Examples of renovation and re-insulation of an existing roof.

- Converting a cold roof to a warm roof. The old roof covering (which must be air- and vapour-impermeable) functions as a vapour barrier after the renovation. Insulation is installed whose thickness is relative to the moisture load class for the building (cf. Tables 1 and 28). The vent openings in the old roof are sealed after approx. one year when it can be ascertained that the assembly is free of unacceptable moisture.

- Renovation and re-insulation of warm roof. Re-insulating on top of the existing warm roof will always improve moisture conditions. There are therefore no requirements for the quantity of insulation material except that U-values specified by the Building Regulations. Tapered thermal insulation is fitted and a new roof covering is installed. This will ensure that water on the roof surface can drain away, and that no moisture absorption will occur as a result of moisture transport from the inside.

- Exterior additional insulation on a cold roof with tapered thermal insulation to improve falls. The requirements listed in Table 28 must be fulfilled by the thickness of the thinnest part of the structure. Vent openings are sealed as outlined in Figure 241a

8.3.2 Converting a Cold Roof to a Warm Roof

Cold roofs with bituminous felt or foil coverings can be converted into warm roofs during renovation by means of exterior re-insulation and a new roof covering.

The old roof covering will then function as a vapour barrier in the new warm roof. Therefore, it should be ensured that the old roof covering is airtight around roof lights, penetrations, roof edges, and other verges.

To avoid moisture absorption, the insulance factor of the new exterior insulation must have a specific min. value relative to the existing insulance factor. This min. value depends on the specific moisture load class that the roof is intended to meet. In most cases, the insulance factors are largely proportional to the relative thickness of the new and the original insulation. If new insulation is used with a significantly lower λ-value than the original, the thickness of the new exterior insulation can be reduced proportionally to the value between the insulation thicknesses.

If the λ-value of the new insulation is only slightly lower than the original, it merely indicates that the relative insulation thickness is applied to be on the safe side. Table 28 sets out guidelines for the ratio between the insulance factors of the existing structure and the new insulation.

Table 28. The required insulance factor of the new insulation relative to the insulance factor of the original assembly when converting a cold roof to a warm roof or for the exterior re-insulation of a warm deck. The proportional ratios specified are calculated based on the maximum moisture content in the relevant class. If it can be ascertained that the moisture content is less (e.g., with climate control), calculations may indicate that the new insulation’s required insulance factor can be reduced.

| Moisture Load Class | Proportional Insulance Factors of New and Old Insulation, Respectively. |

|---|---|---|

1 | 1:1.5 | |

2 | 1.5:1 | |

3 | 3:1 | |

4 | 8:1 | |

5 | To be calculated |

Example

The minimum re-insulation thickness of traditional roof structures is shown in the figure in Table 28 and is determined by the moisture load class as follows:

Structure:

- Bituminous felt or roofing foil

- x mm re-insulation, λ-value = 0.036 W/mK

- Existing bituminous felt

- 22 mm plywood

- 50 mm cavity space

- 100 mm insulation, λ-value = 0.039 W/mK

- Spaced battens

- Vapour barrier

- 13 mm plasterboard

Calculation of insulance factors (exclusive of roof covering):

Material | Thickness | Thermal Conductivity | Insulation |

|---|---|---|---|

d | λ | R = d/λ | |

m | [W/m∙K] | [m2K/W] | |

Ext. transition | 0.04 | ||

Insulation | x | 0.036 | x/0.036 |

Total insulance (top) | 0.04 + x/0.036 | ||

Plywood | 0.022 | 0.11 | 0.20 |

Cavity space | 0.05 | 0.16 | |

Insulation | 0.1 | 0.039 | 2.56 |

Spaced battens | 0.019 | 0.16 | |

Vapour barrier | - | ||

Plasterboard | 0.013 | 0.25 | 0.05 |

Interior transition | 0.10 | ||

Total insulance (bottom) | 3.24 |

The insulation thickness can now be calculated according to the insulance

Kinsulance outlined in Table 28 (e.g., where 1:1.5 equals the value 2/3):

Kinsulance outlined in Table 28 (e.g., where 1:1.5 equals the value 2/3):

Where Rsu is the external surface resistance (0,04 m2K/W)

If this is inserted into the example above, the result in moisture load class 2

(Kinsulance = 1.5):

(Kinsulance = 1.5):

The calculation above can be presented in graphical form for this specific structure as:

8.3.3 Re-Insulating Vented Loft Spaces

Vented loft spaces are typically found in unutilised roof assemblies (e.g., structures using lattice trusses) (see Figure 242), or the upper area (apex) above an attic truss (see Figure 245).

When re-insulating the loft space between the heated accommodation below and the overlying vented loft space, both heat and moisture conditions must be considered. The ceiling facing a cold space must typically contain the following elements (listed from the bottom up):

- Ceiling cladding

- Vapour barrier

- Foot of rafter (or tie beam)

- Thermal insulation between and above the rafter feet (or tie beams).

Thermal bridges may occur (e.g., at the foot of rafters). These can be reduced significantly if it is possible to link the re-insulation of the ceiling with the insulation in the exterior wall. If there are casings at the eaves, continuous insulation of both the ceiling and exterior walls can be established. If the thermal bridge remains unbroken, re-insulation may mean that the wall will be colder along the ceiling. However, the total heat loss will be reduced by the re-insulation.

Figure 242. A diagram of an old roof with lattice trusses and vented unutilised loft space without re-insulation.

Re-Insulating a Loft Space from Above

If the loft space is unutilised, and there is enough space, re-insulating from above is the easiest solution. For low-slope roofs, it may be difficult to work in the loft space and it may therefore be advisable to re-insulate using loose-fill, for reasons of occupational health and safety.

The choices available for re-insulating from above depend on the quality and installation of the existing vapour barrier (see Section 8.2.3, Vapour Barriers and Roof Renovation).

Figure 243 shows an example of a vented loft space re-insulated from above.

Figure 243. A diagram of an eave in a vented loft space which has been re-insulated from above. A wind barrier has been fitted between rafters to allow ventilation through the eave. A vapour barrier is installed from below directly onto the existing ceiling cladding and new ceiling cladding is then installed. The vapour barrier in the ceiling is joined tightly against adjoining walls by butyl-tape bonding and a clamping strip. Any existing vapour barrier need not be removed as it is on the warm side of the insulation material and there will be no resultant risk of moisture absorption.

Re-Insulating a Loft Space from Below

When re-insulating a loft space from below, it will usually be necessary to install a vapour barrier joined tightly to the walls. In walls with an actual vapour barrier (e.g., a foil barrier), tightness is best ensured by bonding the wall and ceiling vapour barriers together.

For plaster, brick, or aerated concrete walls, the ceiling vapour barrier should be bonded and clamped to the wall (e.g., using foil adhesive or butyl tape with a clamping strip) (see Figure 244).

An existing vapour barrier or other vapour-impermeable layer must normally be removed prior to re-insulating, as it will extend deeply into the insulation layer where there is a risk of low temperatures (see To dampspærrer ved nybyggeri og renovering (Two Vapour Barriers for Renovation and New Build)) (Byg-Erfa, 2018). Since the existing ceiling will not be visible after the re-insulation process, any dense paint treatment (such as oil paint) on a plaster ceiling can be removed to prevent this from functioning as a vapour barrier. Thereafter a framework containing thermal insulation is installed. It is advisable to re-insulate in several layers, so that the vapour barrier will extend slightly into the structure (max. 1/3 into the insulation for dwellings) to protect it. At the bottom, new ceiling cladding is then installed.

The ceiling cladding must be min. class K1 10 D-s2,d2 (class 2 cladding) for detached single-family dwellings, and class K1 10 B-s1,d0 (class 1 cladding) for multi-storey residential buildings (see Section 2.5, Fire Safety Regulations for Roofs).

Figure 244. An example of a vapour barrier installation against a wall (shown as a plastered brick wall) when re-insulating a loft from below. A length of vapour barrier is bonded (e.g., using butyl tape), and clamped to the exterior wall. After installing the vapour barrier on the rest of the ceiling, the length is taped to the remaining vapour barrier. Taping must be performed on a firm underlay. Thereafter, more thermal insulation can be installed on the underside (if required), before finally installing new ceiling cladding.

8.3.4 Re-Insulating Vented Couple Roofs

Typical vented couple roofs are:

- Couple roof assemblies with a vent space (both flat and pitched)

- The sloping roof in collar roofs

- Vented roofing slabs.

When re-insulating a vented couple roof with a continuous roof covering, the roof can be converted into an unvented one (i.e., a roof with a vapour-permeable roofing underlayment). This will gain structural height, which can be used for additional insulation. However, the height gained will rarely be significant (typically max. 70 mm). A vented couple roof with a continuous roof covering can be converted into a warm roof during the re-insulation process.

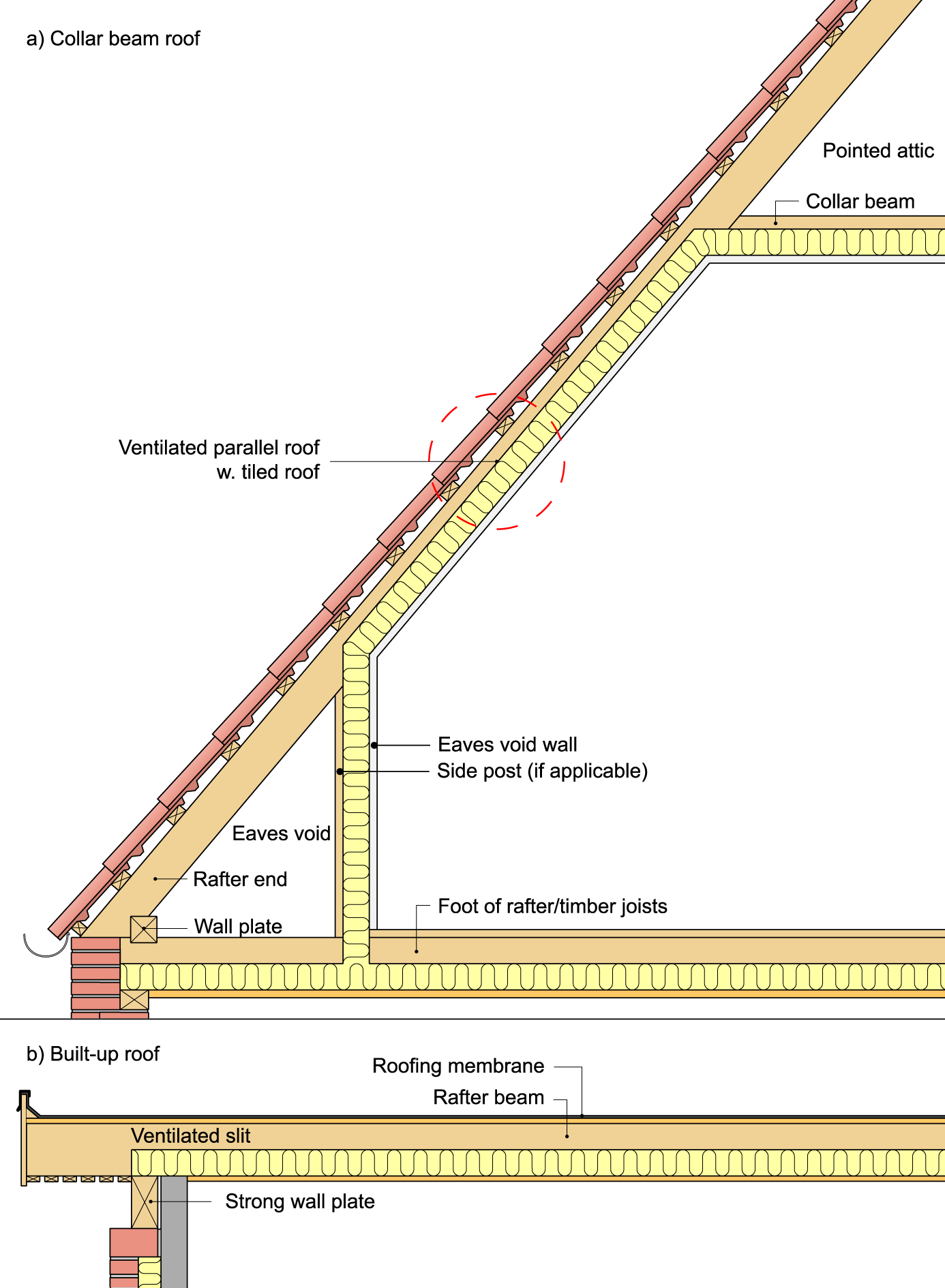

Roof assemblies with both a vented couple roof and vented spaces (e.g., an attic-trussed roof with crawl space and/or apex) (see Figure 245a) require a combination of solutions outlined in this section with solutions outlined in Section 8.3.3, Re-Insulating Vented Loft Spaces, and Section 8.3.6, Re-Insulating Crawl Spaces.

If not all parts of the roof are re-insulated, care must be taken to join the vapour barrier (if applicable) carefully to adjoining building parts in the structure that are not re-insulated. This is true even if the adjoining buildings parts are not vapour-impermeable, but only airtight (e.g., an old plastered surface).

Figure 245. A diagram of two typical vented couple roof structures before re-insulation.

- A traditional clay-tiled roof on attic trusses with a utilised top floor where the middle part (with the sloped ceiling) constitutes the vented couple roof, while the crawl space and apex, in principle, are vented loft spaces.

- A vented couple roof (built-up roof) with a shallow slope and a membrane roof

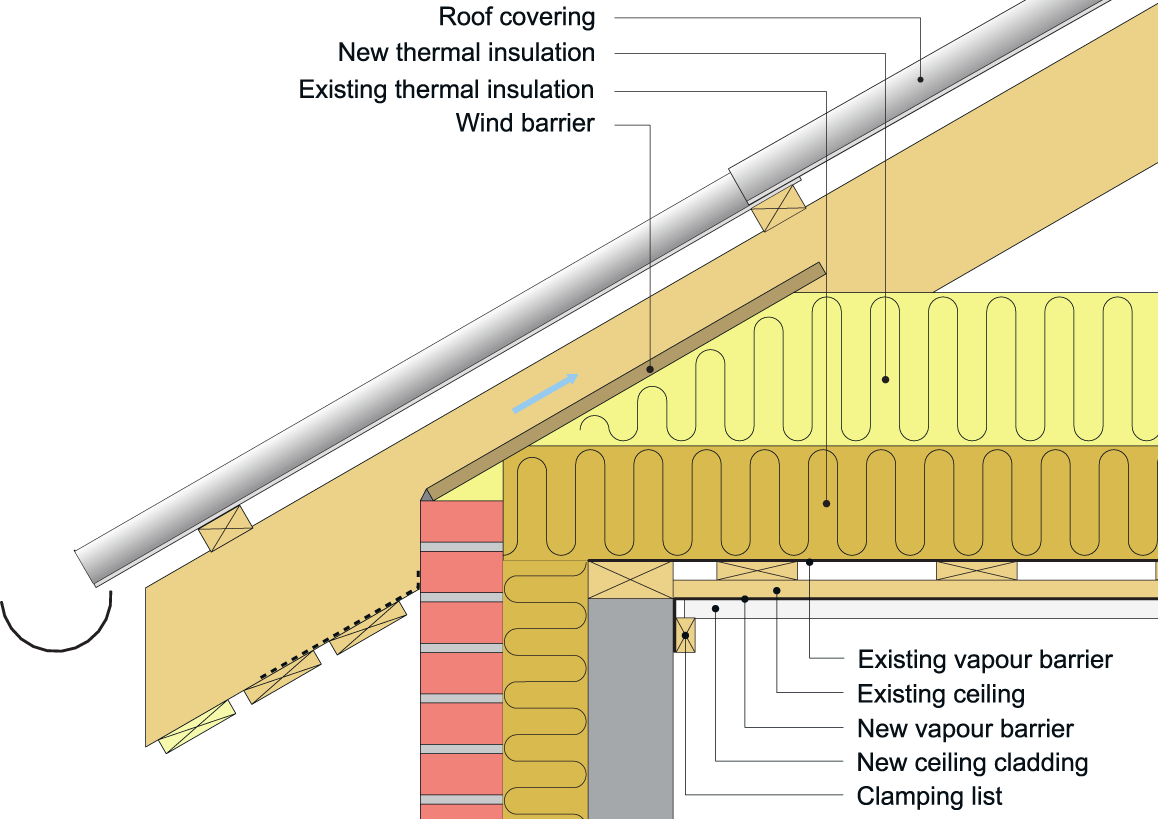

Re-Insulating from the Outside

Re-insulating a cold couple roof with a membrane covering (such as a flat built-up roof) is outlined in Section 8.3.2, Converting a Cold Roof to a Warm Roof.

Exterior re-insulation of vented tiled or slated couple roofs is mostly performed when replacing the existing roof covering. Extra space for re-insulation can be gained by firring the rafters on the outside and thereby raising the new roof covering relative to the old one (see Figure 246).

When re-insulating from the outside by firring the rafters (and thereby raising the roof), the eaves will typically have to be changed to maintain the necessary roof ventilation. The construction follows the same rules as for ventilation outlined in Section 2.3, Roof Ventilation.

The installation of vapour barriers (from both above and below) is carried out as outlined for the re-insulation of a vented loft space (see Section 8.3.3, Re-Insulating Vented Loft Spaces).

Solutions for exterior re-insulation and installation of vapour barriers in roofs where the vented couple roof is connected to a crawl space is outlined in Section 8.3.6, Re-Insulating Crawl Spaces.

When installing a new discontinuous roof covering such as a tiled or slated roof, this normally means installing roofing underlayment as well. This is because it is impossible to inspect and repair the underside of the roof covering in couple roofs.

Figure 246. A schematic of the exterior re-insulation of an old vented couple roof with a new firm roofing underlayment and roof tiles. A plank has been used as firring on the side of existing rafters to make space for additional insulation. The vent space under the underlayment must have a minimum mean height of 45 mm (firm underlayment). If roll material or flexible sheeting (e.g., wood-fibre sheets) is used as roofing underlayment, the vent space design height must be min. 70 mm, because the underlayment will be suspended between rafters. In this example, a vapour barrier has been installed from below onto the existing ceiling and finished off by sheet cladding.

Re-Insulation from Below

The roof slope and covering are immaterial when re-insulating vented couple roofs from the inside. For all roof slopes and roofing materials, re-insulating from the inside will result in a reduced ceiling height.

The need for a new vapour barrier is evaluated based on the position and condition of the existing one.

If the existing vapour barrier is close-fitting and will be extending max. 1/3 into the thermal insulation layer measured from the warm side (in moisture load classes 1 and 2) once the re-insulation is complete, there will be no need for a new vapour barrier and the old one can normally be retained. In other moisture load classes, more insulation is required on the cold side (see Tables 5 and 28).

If the vapour barrier is defect, a new one must be installed. Likewise, a new vapour barrier must be installed if the existing one will be extending more than 1/3 into the thermal insulation layer (in moisture load classes 1 and 2) once the re-insulation is complete – in that case, the original vapour barrier will have to be removed!

It is usually easier to place the vapour barrier on the inside of the rafters where the installation is unbroken. Joints to heavy walls of e.g., brick or aerated concrete must be sealed. In practice, this is best done by clamping and bonding the vapour barrier to the wall as in the principle shown in Figure 244 (see also Section 8.2.3, Vapour Barriers and Roof Renovation). Joints to light walls with vapour barriers should be carried out by taping the new ceiling vapour barrier to the one in the wall.

Interior re-insulation of a vented couple roof corresponds, in principle, to interior re-insulation of a vented loft space (see Section 8.3.3, Re-Insulating Vented Loft Spaces).

Methods for re-insulating a vented couple roof connected to a crawl space are outlined in Section 8.3.6, Re-Insulating Crawl Spaces.

8.3.5 Unvented Couple Roofs

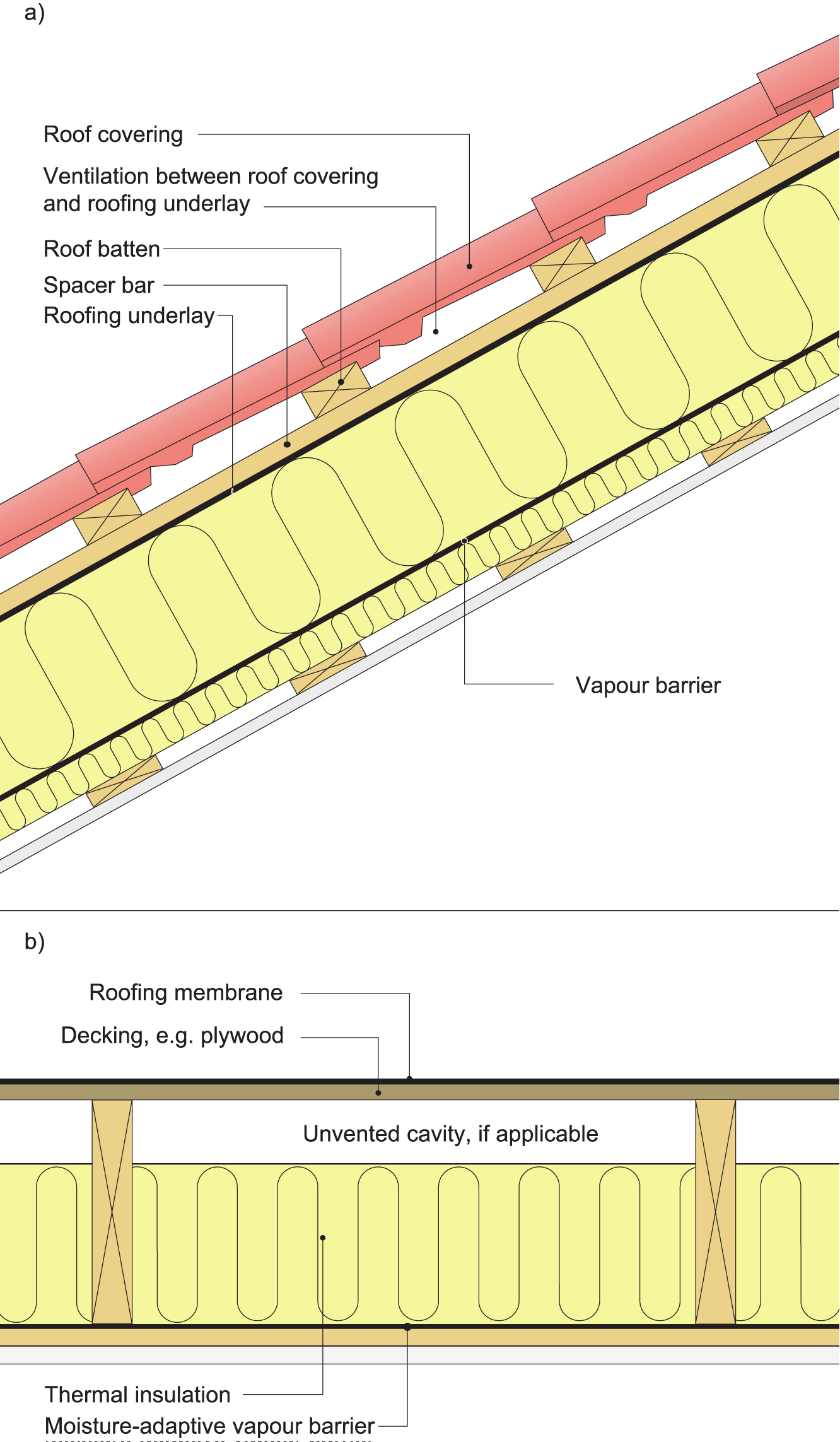

Unvented couple roofs are typically flat roofs made of roofing slabs or pitched couple roofs with a vapour-permeable roofing underlayment. Examples of constructing unvented roofs are shown in Figure 247.

Re-insulating pitched roofs with a vapour-permeable roofing underlayment is carried out in the same way as for similar roofs with a vented roofing underlayment (see Section 8.3.4, Re-Insulating Vented Couple Roofs).

Re-insulating unvented flat couple roofs is normally carried out as outlined in Section 8.3.2, Converting a Cold Roof to a Warm Roof.

Figure 247. Basic diagram of two types of unvented couple roof without re-insulation.

- Pitched roof with vapour-permeable roofing underlayment and discontinuous roof covering, e.g., roof tiles or sheets.

- Unvented couple roof with roofing membrane and moisture-adapt.

8.3.6 Re-Insulating Crawl Spaces

In roof assemblies with crawl spaces, it is necessary to thermally insulate the crawl space in the same way as the rest of the roof. In principle, crawl spaces are loft spaces and are typically found in attic-trussed roofs (see Figure 245a). Due to the cramped conditions and often complex design of crawl spaces where several building parts come together, the buildability is often vital for the choice of re-insulation.

Re-insulating crawl spaces can be done in two different ways:

- Insulating along the roof, thereby achieving a warm crawl space, i.e., the crawl space lies on the warm side of the insulation

- Insulating the floor and wall of the crawl space, thereby achieving a cold crawl space, because the crawl space lies on the cold side of the insulation.

Which solution to choose, depends chiefly on the rafter and eaves design, available space, position of installations, and whether the roof or interior walls are replaced during the re-insulation process. Just because the existing thermal insulation has been fitted vertically and horizontally, the re-insulation need not be carried out in the same way.

In the main, a warm crawl space is preferable, because the crawl space can then be utilised. Especially where the crawl space contains installations, a warm crawl space is an advantage, as many installations are not frost-proof. Besides, it is easier to inspect and maintain such installations and any heat loss from these will be beneficial to the house.

If a cold crawl space is opted for, installations sensitive to frost must be insulated separately.

As work in crawl spaces often has to be executed in very cramped conditions, it is necessary to be aware of occupational health and safety regulations when carrying out such work (cf. Section 10, Health and Safety Issues When Working on Roofs). Since notably re-insulation work from the inside usually means difficult working conditions, we recommend that the re-insulation of crawl spaces, whenever possible, be carried out from the outside.

Installing Vapour Barriers in Crawl Spaces

Vapour barriers in crawl spaces must be joined to the vapour barrier/ airtight layer in the part of the roof where there is a vented couple roof. Buildability has high priority to ensure the best possible installation of the vapour barrier, in particular. In practice, it is difficult to ascertain that the new vapour barrier is tight when installing it from inside the crawl space due to the cramped conditions. The working conditions can be improved if the roof covering above the crawl space can be removed, so that the work can be done from the outside, e.g., in connection with replacing the roof covering.

When installing the vapour barrier, the following critical points should be observed:

- The vapour barrier must fit closely to the vapour barrier in the exterior wall/airtight enclosure.

- The vapour barrier must fit closely to the vapour barrier in the roof (if applicable)/airtight enclosure

- Joints in the vapour barrier must be made tight by bonding or taping the lengths on firm underlay.

Furthermore, tightness must be secured between exterior wall and wall plate, so that outdoor air cannot flow under the wall plate into the ground floor accommodation space.

Furthermore, issues concerning installation of vapour barriers when re-insulating roofs are outlined in Section 8.2.3, Vapour Barriers and Roof Renovation, and Section 8.2.4, Airtightness and Roof Renovation.

Re-Insulating from the Outside

Re-insulating crawl spaces from the outside is a very good idea in conjunction with replacing the roof covering, as this means removing the existing roof covering. The extra space needed for re-insulation can often be gained, in roof-covering replacements, by firring the rafters on the outside, thereby raising the new roof covering relative to the old one.

Alternatively, re-insulation from the outside can be done by only removing the lower part of the roof covering – in which case, it will not be possible to fir the rafters on the outside.

When re-insulating is done from the outside, the utilised loft space will not be touched and the interior wall and ceiling cladding can be preserved.

Care must be taken not to block ventilation at eaves, under the roof covering, or roofing underlayment, see Section 8.2.1, Ventilation and roof renovation.

Warm Crawl Space – From the Outside

Re-insulating a couple roof with a warm crawl space from the outside is, in principle, the same as re-insulating a vented couple roof from the outside, see Section 8.3.4, Re-insulating Vented Couple Roofs. However, it will be necessary to install a substrate of e.g., lathing for fixing the thermal insulation if the existing thermal insulation was not carried along the roof. The vapour barrier can be installed from the outside against the battens as lengths between each set of rafters. The vapour barrier is carried min. 50 mm up the sides of rafters and fixed, e.g., with butyl tape, and subsequently clamped with a clamping strip (see Figure 239 or 248). The vapour barrier in sloping walls must be joined to the exterior wall in an airtight joint, e.g., to the wall plate. Finally, the insulation is installed, roofing underlayment, if applicable, and roof covering.

Cold Crawl Space – From the Outside

Re-insulating a couple roof with a cold crawl space from the outside is, in principle, the same as for re-insulating a vented couple roof from the outside, see Section 8.3.4, Re-insulating Vented Couple Roofs. Inside the crawl space, the vapour barrier is laid between rafters/crawl space posts in an unbroken sequence in the transition from crawl-space floor to crawl-space wall (see Figure 248).

The vapour barrier can be installed from the outside against the battens as lengths between each set of rafters. The vapour barrier is continued min. 50 mm up the sides of rafters and fixed (e.g., with butyl tape, and subsequently clamped with a clamping strip) (see Figure 248). The vapour barrier in sloping walls must be joined to the exterior wall in an airtight joint (e.g., to the wall plate). Finally, the insulation is installed, followed by roofing underlayment (if applicable), and roof covering.

Figure 248. A schematic of the re-insulation of a couple roof (from the outside) with cold crawl space in a roof assembly with a traditional storey partition of a layer of timber joists with pugging, plastered walls, and ceiling. Re-insulation is performed from the outside along the crawl-space wall and floor in connection with the firring of rafters and the installation a new roof covering. The existing crawl-space, wall, and ceiling are retained. Therefore, the vapour barrier is installed from the outside according to the principles outlined in Figures 239 and 240. The insulation of the crawl-space wall is fixed using wire or wood boards. The vapour barrier on the crawl-space floor and wall must be joined in an airtight joint and, similarly, the floor vapour barrier must be joined to the exterior wall or wall plate in a tight joint. Finally, the insulation is installed, followed by roofing underlayment (if applicable), and roof covering (Møller, 2012).

Re-Insulating from the Inside

Re-insulating a crawl space from the inside is only done where the roof covering should neither be tampered with nor replaced.

Re-insulating from the inside usually results in inferior working conditions compared to similar work from the outside due to the cramped conditions.

Re-insulation from the inside means touching neither roof covering nor roofing underlayment (if applicable). A precondition for re-insulating from the inside is that the existing roof covering and underlayment (if applicable) are watertight to the outside.

Care must be taken not to block ventilation at eaves under the roof covering or roofing underlayment (see Section 8.2.1, Ventilation and Roof Renovation).

Warm Crawl Space – Re-Insulated from the Inside

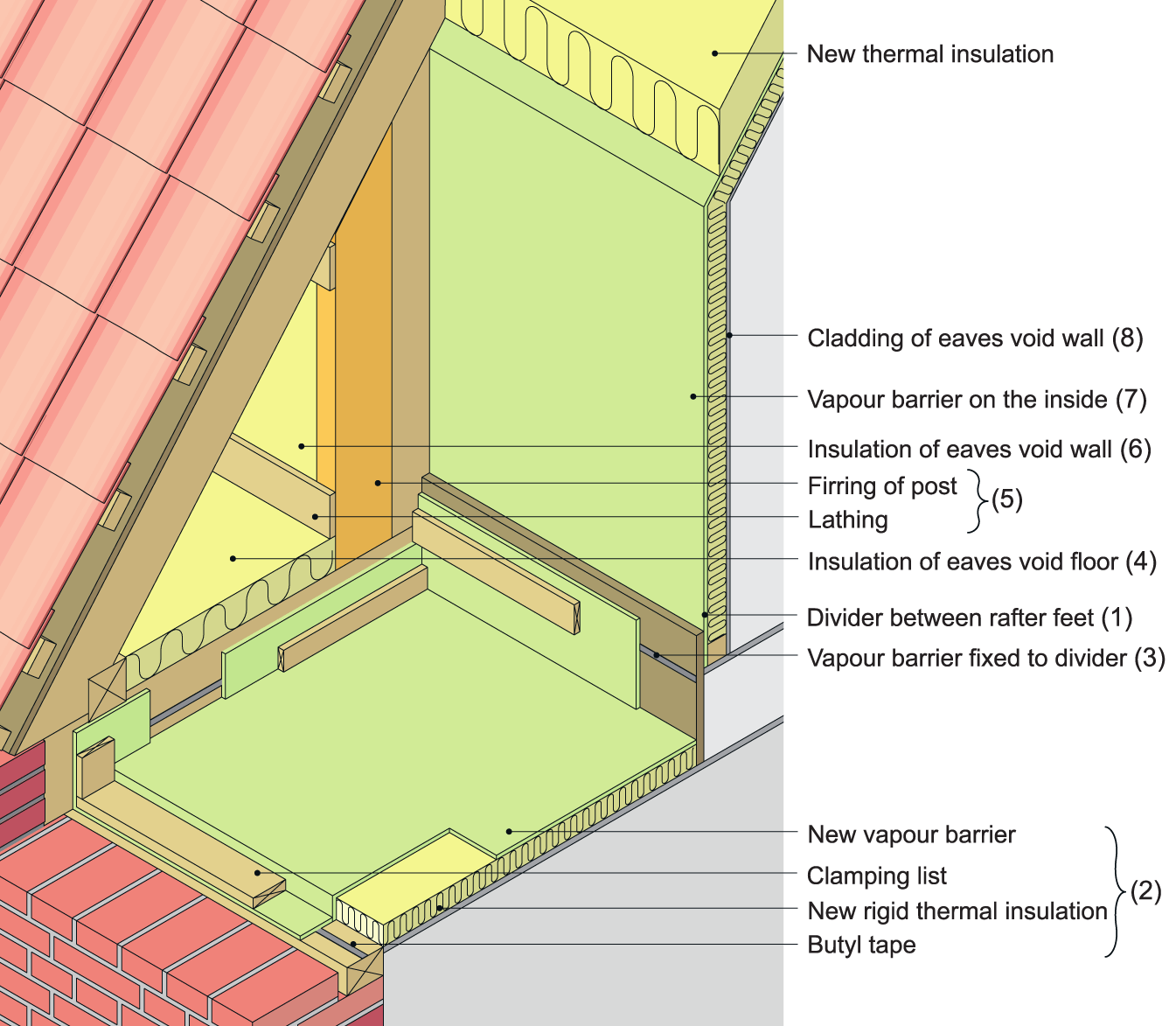

Re-insulating a couple roof from the inside and establishing a warm crawl space is possible and especially simple in attic-trussed roofs without supporting crawl-space posts. In such cases, the vapour barrier can be carried unbroken on the inside of the rafters to the eaves. If removing the crawl-space posts is not possible, sleeves or a vapour-impermeable divider (e.g., plywood) can be used to make sure the vapour barrier is tight around the posts (see Figure 249).

In the transition between eaves and exterior wall, the vapour barrier must be broken across the foot of rafters in order to to connect it to the exterior wall. Special care should be taken when making tight joints around the foot of rafters. A vapour-impermeable divider (e.g., plywood) could be inserted between the rafters and continued across the foot of rafters (see Figure 249). Joints between divider and rafters are sealed using elastic caulking compound.

The new thermal insulation along the roof in the crawl space is placed on firring on the inside of rafters and wire-fixed, for example.

The ventilation conditions in the roof assembly in the re-insulated crawl space must correspond to the existing couple roof (i.e., they should either be vented (see Section 8.3.4, Re-insulating Vented Couple Roofs) or unvented (see Section 8.3.5, Unvented Couple Roofs)).

Figures 249 and 250 show examples of re-insulation (from the inside) of vented couple roofs with warm crawl spaces.

Figure 249. An example of re-insulation (from the inside) of a couple roof with a warm crawl space in a multi-storey residential building with a traditional storey partition of a layer of timber joists with pugging. Rafter ends have been firred to provide space for additional insulation. At the eaves, the existing crawl-space floor and inserts are removed to enable sealing with dividers between rafter ends at eaves. The dividers are sealed to the surrounding woodwork using caulking compound so that they form a substrate for installing the vapour barrier from the inside. Dividers are also inserted around crawl-space posts. The removed inserts must be subsequently re-established to ensure that the storey partition remains fire resistant (see Figure 250).

Insulation is installed between rafters and firrings and fixed (e.g., with wire or lathing). Finally, the Interior ceiling finish is installed (see www.efterisolering.sbi.dk) (Kragh et al., 2014).

Insulation is installed between rafters and firrings and fixed (e.g., with wire or lathing). Finally, the Interior ceiling finish is installed (see www.efterisolering.sbi.dk) (Kragh et al., 2014).

Figure 250. An example of a completed re-insulated couple roof with warm crawl space in a multi-storey residential building with a traditional storey partition of a layer of timber joists with pugging. The vapour barrier in the sloping wall or roof must be joined to the exterior wall (shown as a solid brick wall) with an airtight joint. The joint against the exterior wall can be made against the wall plate (see www.efterisolering.sbi.dk) (Kragh et al., 2014).

Cold Crawl Space – Re-Insulated from the Inside

Re-insulation of a cold crawl-space from the inside will result in little remaining space after installation. Therefore, it might be advantageous to remove the crawl-space wall while the insulation work is being performed. When the crawl space wall is subsequently re-installed, care must be taken to fix it securely.

It is normally difficult to join a new vapour barrier (installed between the rafter feet in the crawl-space floor) with the vapour barrier in the crawl-space wall. In practice, this can be achieved in several stages (as shown in Figure 251).

- A vapour-impermeable divider (e.g., plywood) is installed between the rafter feet underneath the future crawl-space wall. The divider is joined to the rafter feet in a vapour-impermeable joint using tape or caulking compound.

- The vapour barrier is installed and fixed to the exterior wall or wall plate and rafter feet, potentially on a substrate of rigid-foam thermal insulation (as shown in Figures 251 and 252).

- The vapour barrier in the floor is fixed to the divider.

- The thermal insulation is installed on the crawl-space floor.

- Lathing is installed on the reverse side of the crawl-space posts or on the firring (if applicable) to fix the insulation on the crawl-space wall.

- Thermal insulation is installed in the crawl-space wall.

- The vapour barrier is installed on the inside of the crawl-space posts and divider and a tight joint is made with the divider and sloping ceiling.

- New cladding is mounted on the crawl-space wall.

The vapour barrier between rafters and to the exterior wall can be fixed as shown in Section 8.2.3, Vapour Barrier and Roof Renovation.

For dwelling houses where the re-insulation is at least twice as thick as the existing thermal insulation, a horizontal vapour barrier could be laid on the existing thermal insulation and be continued vertically.

Figures 251 and 252 show examples of re-insulation (from the inside), of a vented roof with cold crawl space in a detached single-family dwelling and multi-storey residential building.

Figure 251. An example of crawl space in a detached single-family dwelling with a vented roof, re-insulated from the inside along the crawl-space floor and wall. A new crawl-space wall and sloping wall is established. The vapour barrier in the crawl-space floor and wall is joined on either side of the divider (e.g., plywood) and installed with tight joints between rafter feet underneath the crawl-space wall. The numbers in the figure refer to the descriptions above (Møller, 2012).

Figure 252. An example of a cold crawl space in an old multi-storey building, re-insulated from the inside. The vapour barrier in the floor is installed on a substrate of rigid-foam thermal insulation in the crawl space where the existing pugging has been replaced by new plasterboard inserts (installed on wooden strips on the sides of rafters), thereby retaining fire resistance. The vapour barriers in the crawl-space floor and wall must be joined in a tight joint integral to the continuous airtight enclosure (see www.efterisolering.sbi.dk) (Kragh et al., 2014).