5 ROOF COVERINGS

The roof covering is the de facto rain shield of the roof assembly and may consist of many types of materials. The following are guidelines on how to install several commonly used roofing materials. The guidelines are not exhaustively detailed and manufacturer instructions must always be consulted.

5.1 Types of Roof Covering

Roof coverings are generally classified into two main types, each with a different method of ensuring weathertightness:

- Continuous roof coverings

- Discontinuous roof coverings.

5.1.1 Continuous Roof Coverings

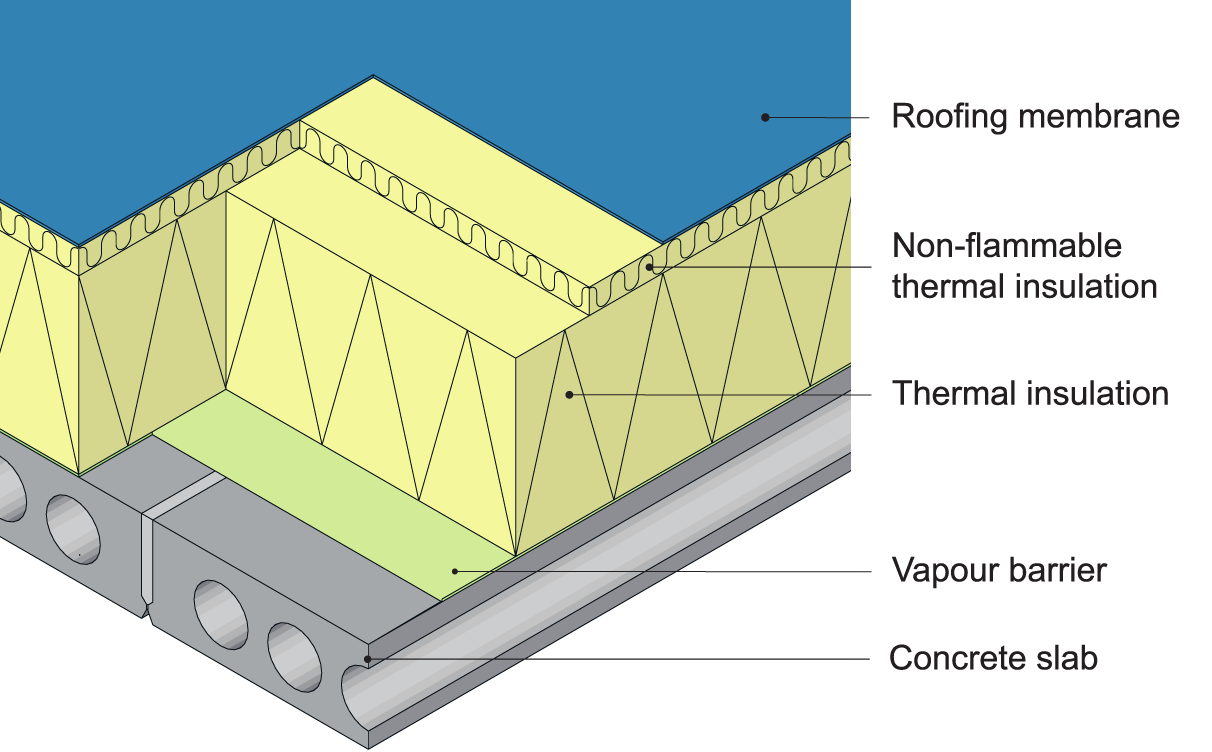

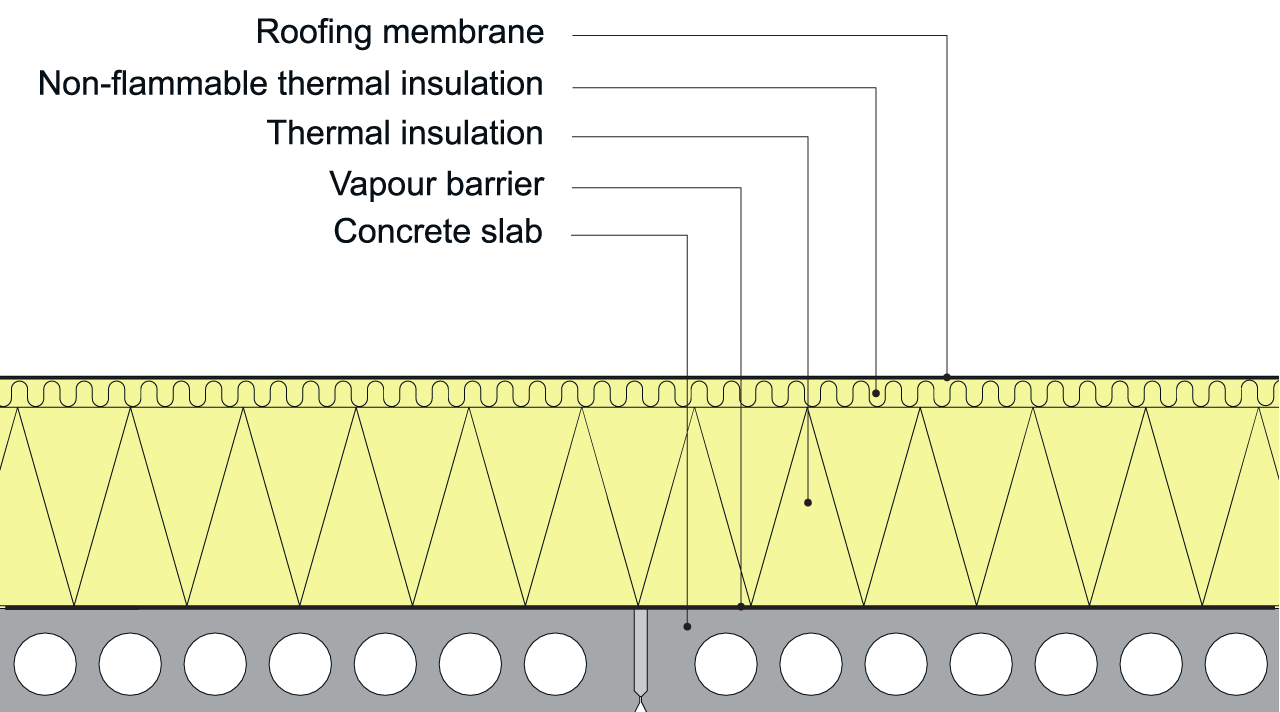

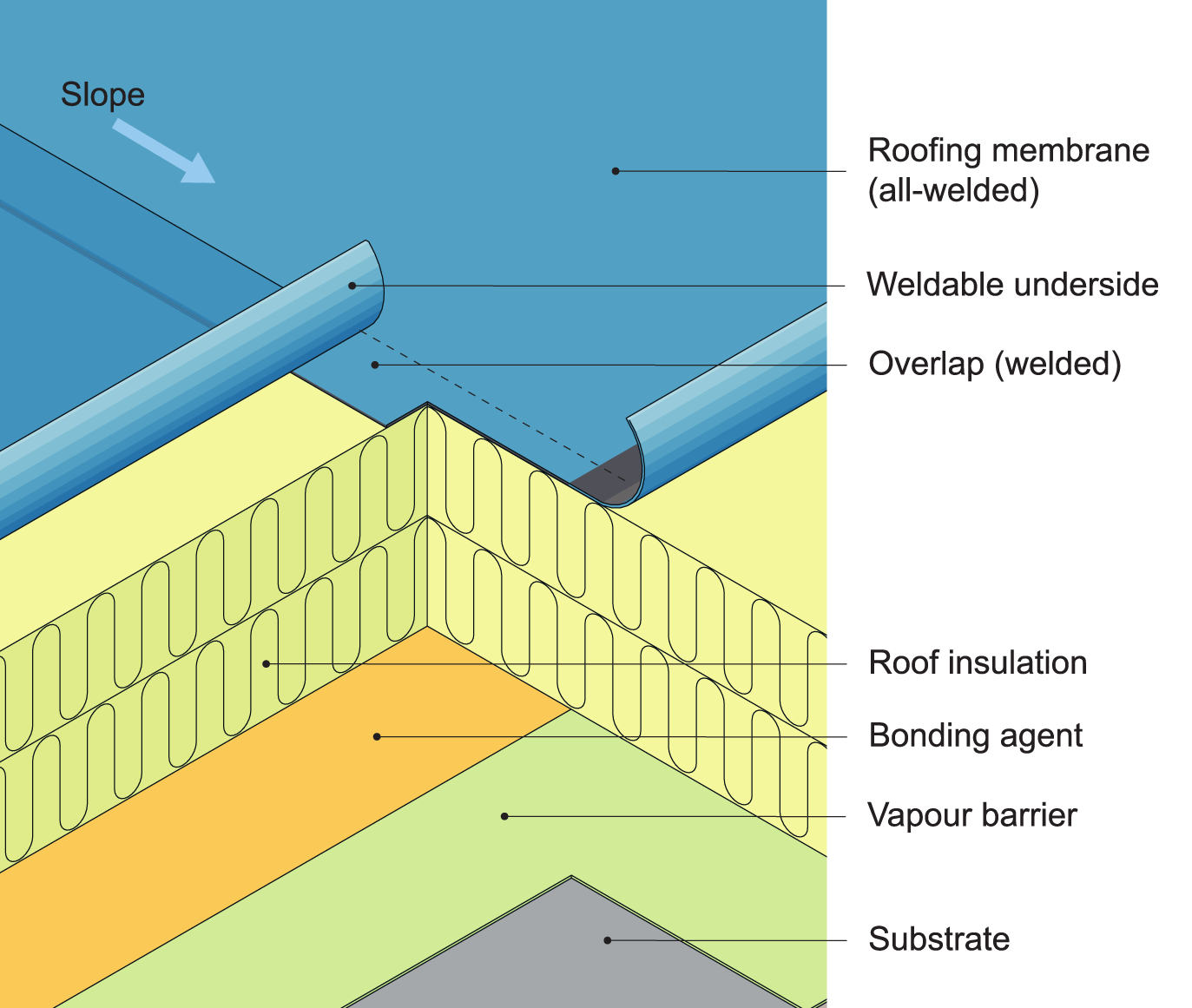

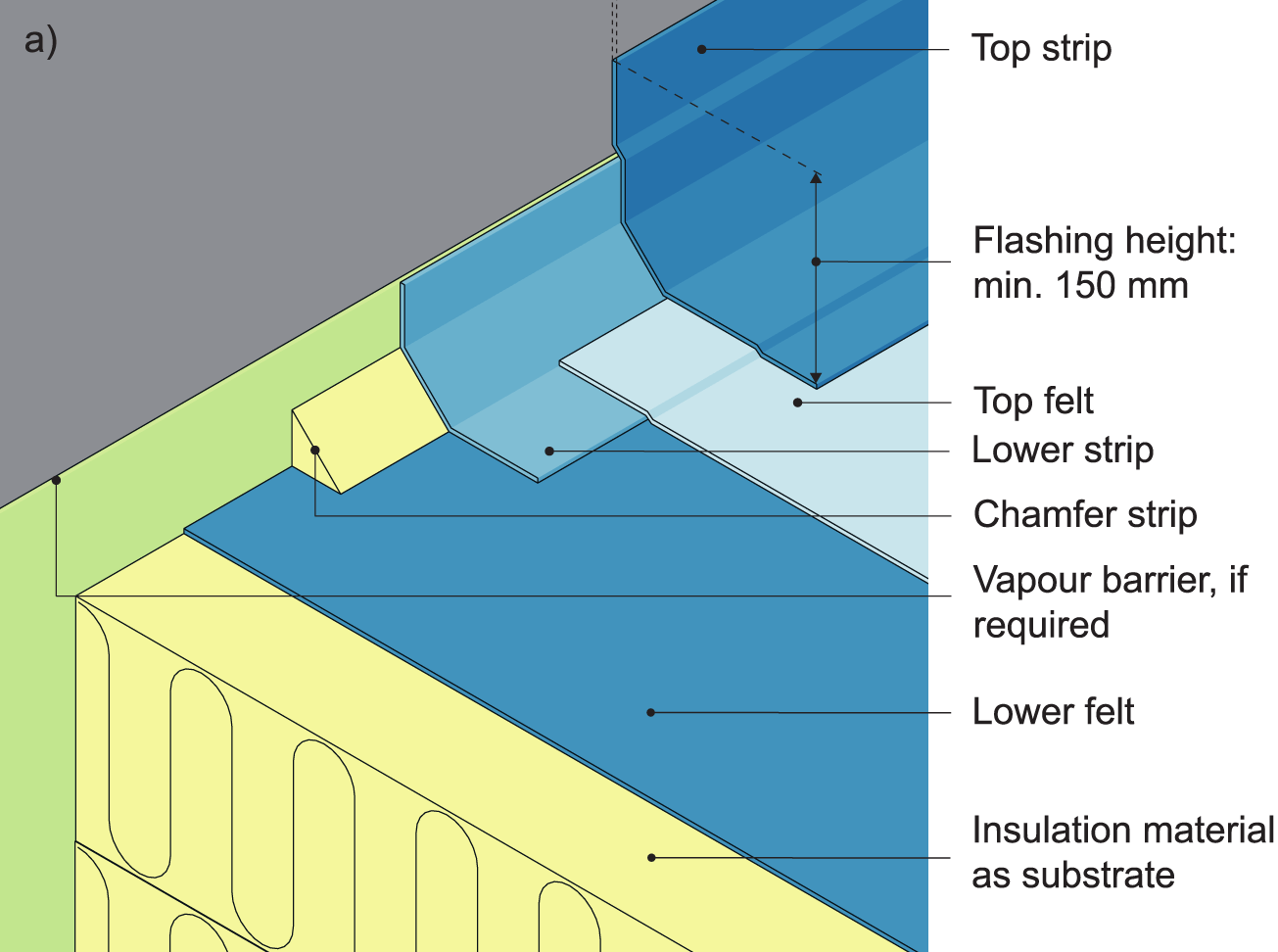

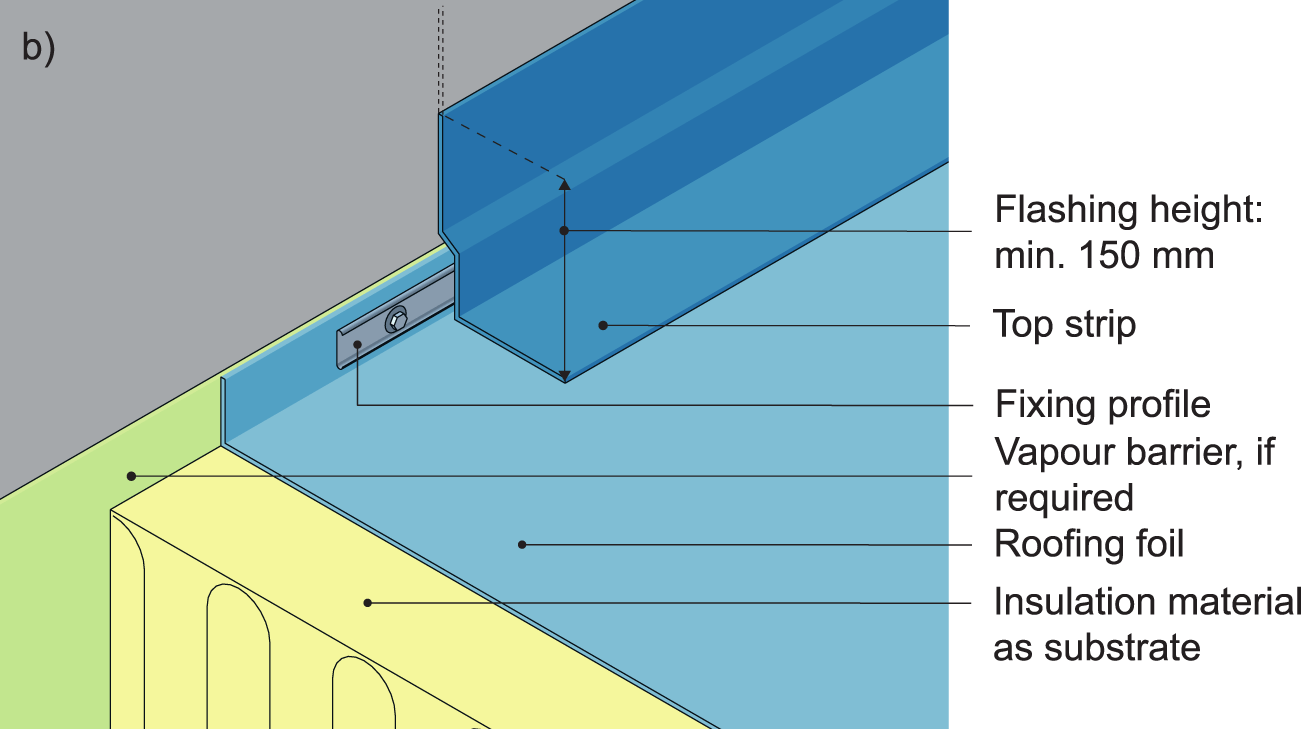

Continuous roof coverings are supplied in rolls which are welded or glued to form a watertight finish on the building site or they are supplied as prefabricated linings. This type of roof covering will provide a watertight roof even at shallow pitches.

Continuous roof coverings include roofing membranes (bituminous felt and roofing foil). Both bituminous felt and roofing foil are available in several material combinations (e.g., APP- or SBS-modified bituminous felt or roofing foil made of EPDM, PIB, PVC, or TPO).

Metal roof coverings such as zinc and copper which are joined mechanically (e.g., with seamed joints) are also continuous roof coverings. Seamed joints are not as watertight as welding or gluing membranes. Therefore, metal roof coverings require a slightly steeper pitch than roofing membranes.

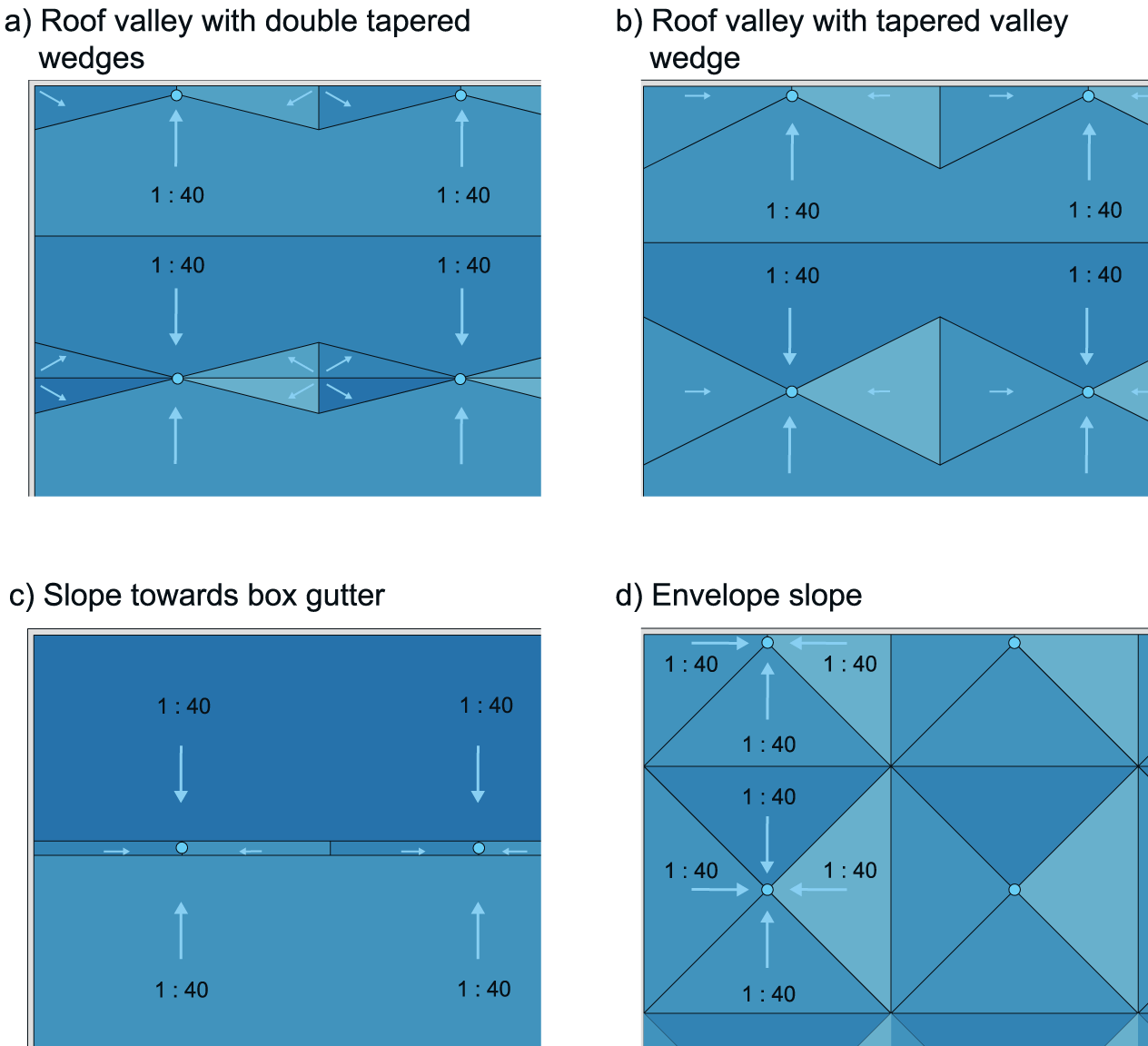

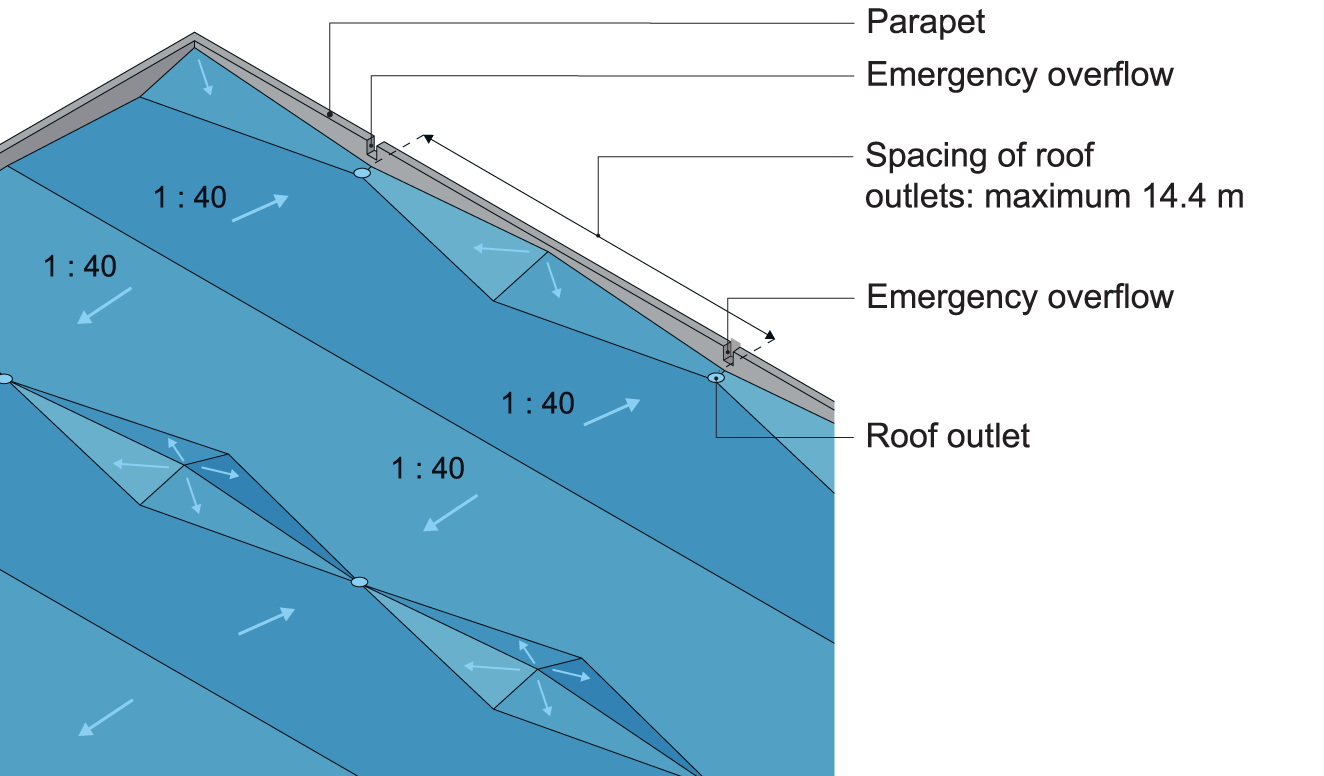

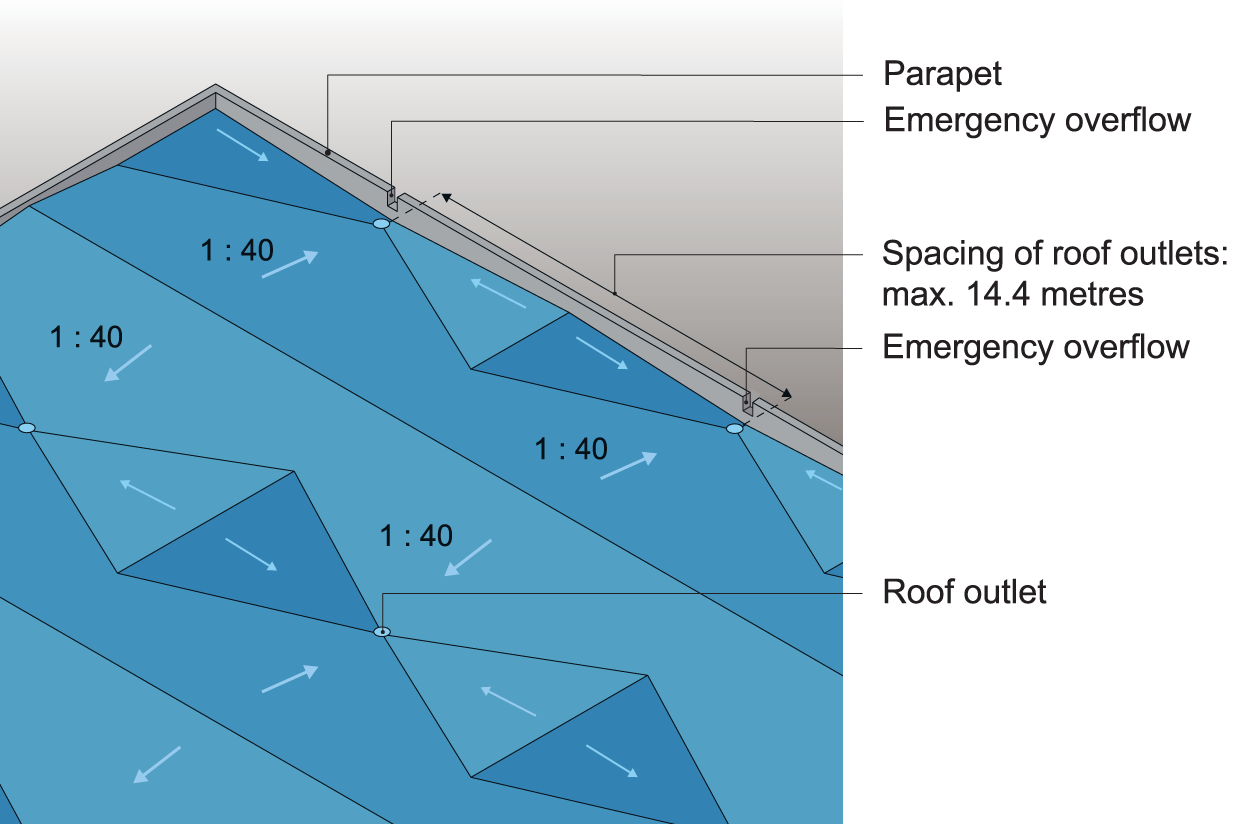

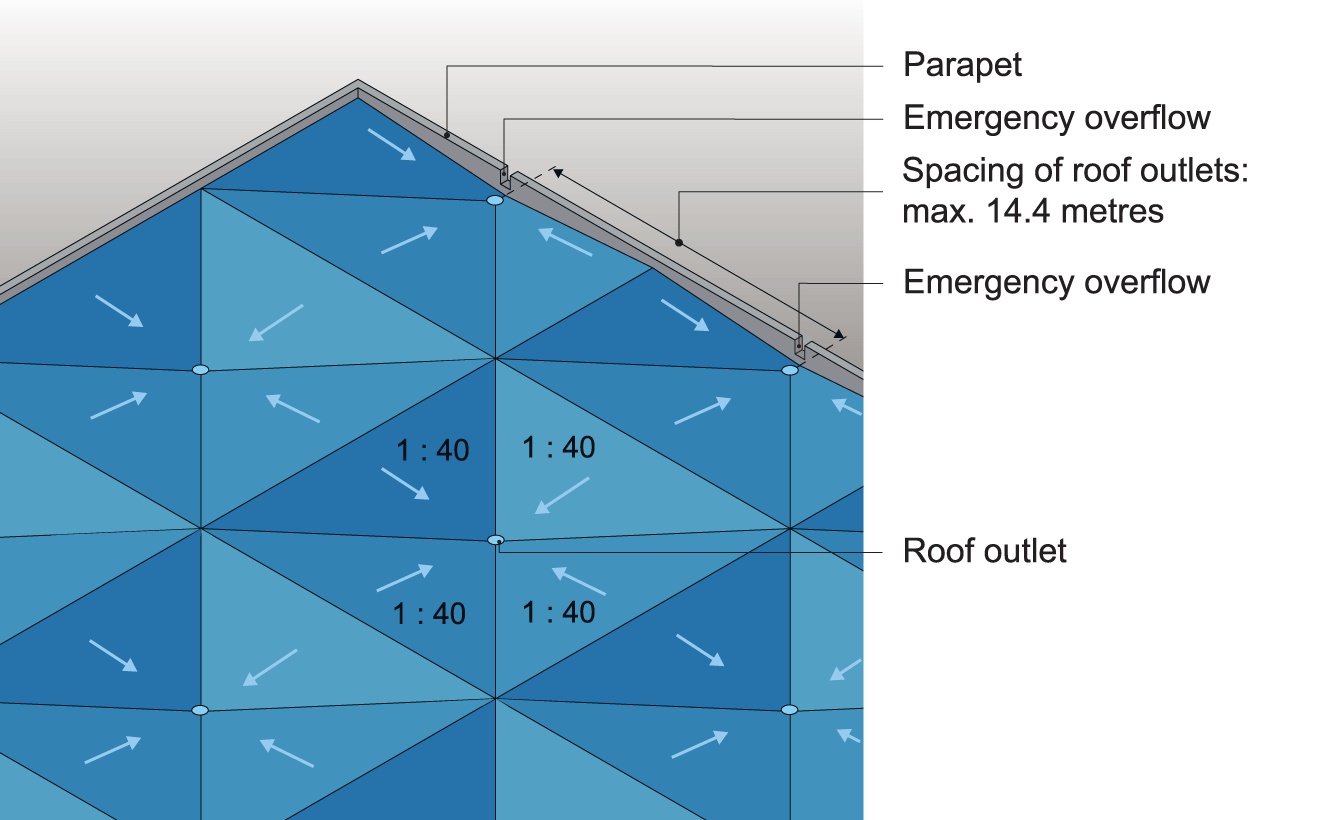

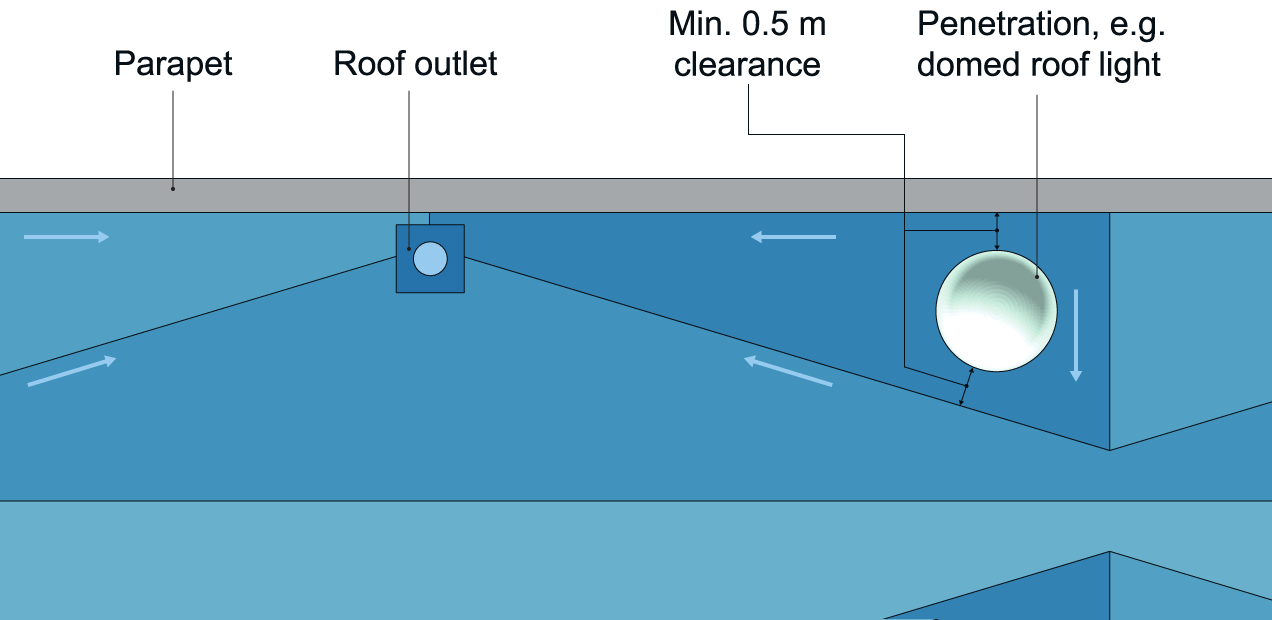

A roof designed with a continuous covering can be constructed with a shallow pitch if water is discharged efficiently, usually to gutters or roof outlets (cf. Building Regulations provisions (BR18, § 328)). Water is typically discharged efficiently if the roof pitch is steeper than 1:40 (cf. Section 1.4 i Bygningsreglementets vejledning om fugt og vådrum (Building Regulations Guidelines for Moisture and Wet Rooms) (Ministry of Transport, Building and Housing, 2018c)).

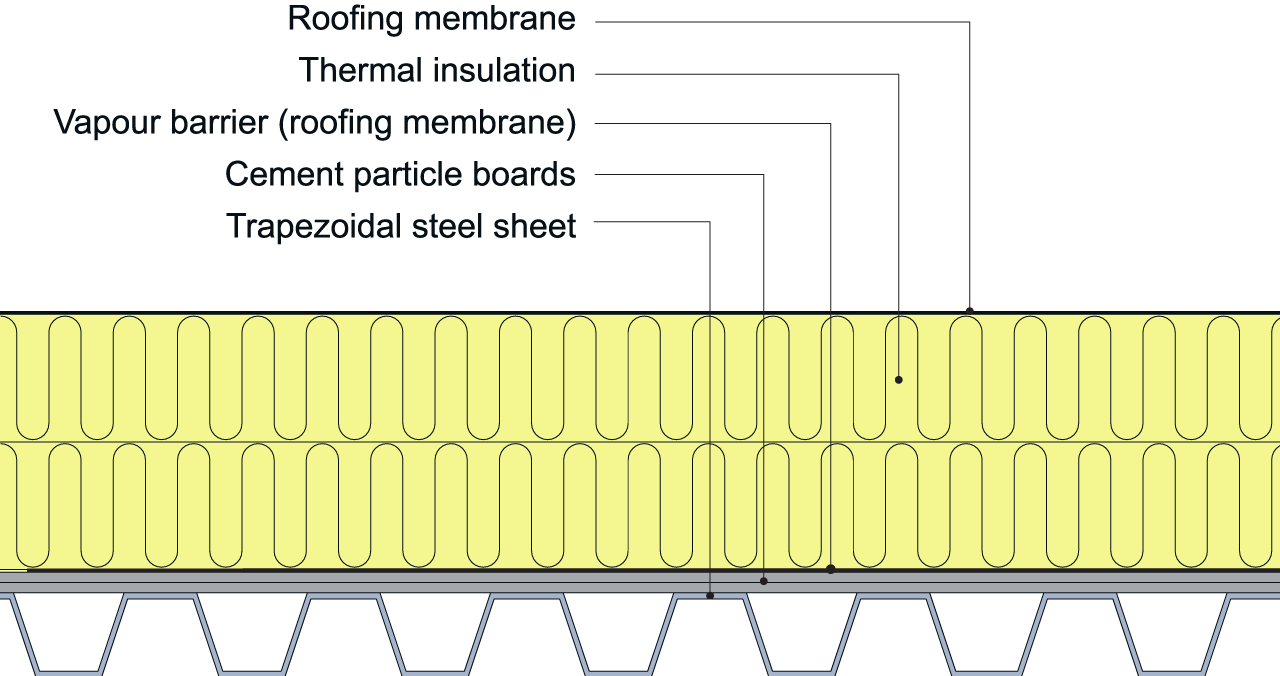

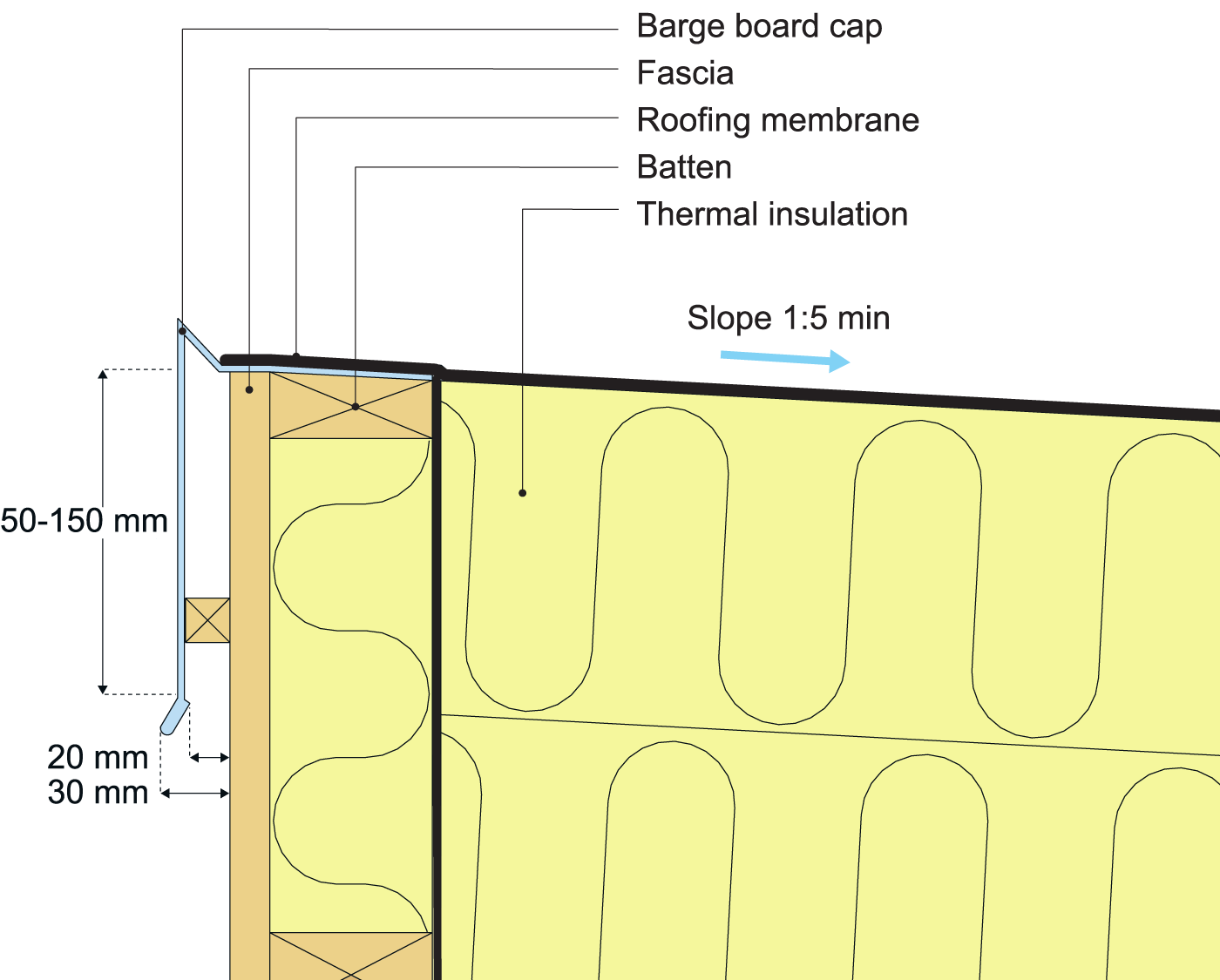

Continuous roof coverings are typically installed on a continuous decking of thermal insulation material, plywood sheets, or planed boards.

5.1.2 Discontinuous Roof Coverings – Roof Tiles, Roof Sheets, and Other Materials

Discontinuous roof coverings include clay or concrete roof tiles, cement-based corrugated sheets, slate (cement-based and natural slate), and metal roof coverings where watertightness is achieved with lap joints.

In this type of roof covering, watertightness is chiefly secured with lap joints or overlap between individual tiles or sheets. Mechanical joints are also used, including seamed joints or click seams. Overlaps and joints can differ in size and geometric design.

In certain types of discontinuous roof coverings with steep-pitched roofs and large overlaps, the roof can only be made watertight with lap joints. Other types require roofing underlayment or other supplementary measures to ensure watertightness.

To a certain extent, underlayment can compensate for openings in the actual roof covering and must be specified to suit the type of roof covering and roof pitch (see Section 3, Roofing Underlayment).

Discontinuous roof coverings are only suitable for relatively steep-pitched roofs and should only be installed on shallow-pitched roofs when appropriate steps have been taken to ensure that the assembly is watertight, using firm underlayment or by following manufacturer’s instructions. A steeper pitch and larger overlaps will generally improve watertightness.

Please note that the shallowest roof pitch of this type of roof usually occurs at the eaves and therefore this pitch determines the type of underlayment that must be used.

Discontinuous roof coverings are usually installed on batten or purlin decking.

5.1.3 Roof Pitch and Areal Weight

Roofs are classed in three types relative to their weight:

- Light-weight roofs

- Heavy-weight roofs

- Extra heavy roofs

In renovations where a heavy-weight roof covering is changed to a lighter covering, care must be taken to ensure that the roof assembly is adequately anchored to secure the lighter roof covering. Conversely, if a light-weight roof covering is replaced with a heavier one, care must be taken to ensure that the structural load-bearing capacity of the assembly is adequate.

Table 16 are examples of light-weight, heavy-weight, and extra heavy roofs and their properties.

Table 16. Examples of roofs classed as light-weight, heavy-weight, and extra heavy (cf. TRÆ 59 (Træinformation, 2009) and TRÆ 65 (Træinformation, 2011)).

Roof Type | Dead Load | Examples |

|---|---|---|

Light-weight roof | 0.25 kN/m² (incl. battens and underlayment) | Roofing membrane on plywood or wood boards Metal sheets on battens, plywood, or wood boards Cement-based corrugated sheets on battens |

Heavy-weight roof | 0.55 kN/m² (incl. battens and underlayment) | Roof tiles on battens (all types) Thatched roofs (unless gypsum-based sheets are used as underlayment, in which case the factor is 750 N/m2) |

Extra heavy roof | 0.80 kN/m² (incl. battens and firm underlayment) | Turves where the thickness or weight must be stated (spacing between rafters is often less than 1.0 metre). |

When selecting a roof covering, consideration must be given to the minimum requirements for roof pitch to ensure that the roof is watertight.

Examples of roof covering materials with indications of min. roof pitch and areal weight are shown in Table 17. In some cases, shallower roof pitches than those stated may be acceptable. However, to ensure a watertight assembly, this should only be executed with prior agreement from the manufacturer.

Table 17. Examples of roof coverings with their minimum roof pitch and approx. areal weight. In each case, manufacturer literature and guidelines concerning minimum roof pitch must be followed. For a conversion table for roof specifications, see Annex C.

Roof covering material | Min. roof pitch [ ° ] | Approx. areal weight [N/m2] |

|---|---|---|

Clay roof tiles – pantile with mortar bedding Clay roof tiles – pantile with underlayment | 40 20 | 450 450 |

Clay roof tiles – interlocking with mortar bedding Clay roof tiles – interlocking with underlayment | 35 15 | 450 450 |

Concrete roof tiles Concrete roof tiles with underlayment Concrete roof tiles with interlocking sealing strips | 45 15 20 | 300 300 380 |

Slate (cement-based) with slate sealant Slate (cement-based) with underlayment Slate (cement-based) laid diagonally with underlayment Slate (natural) with underlayment | 34 18 18 20 | 200 200 200 400 |

Corrugated sheets (cement-based) with sealing strips in horizontal lap joints Corrugated sheets (cement-based) with underlayment Bituminous felt Roofing foil Metal (lengths which are joined on-site, e.g., zinc and copper) with sealant in grooves Metal sheets (prefabricated, factory-coated sheets) | 14 8 | 180 180 |

1.4 1.4 | 100 20-30 | |

3 10 | 20-100 20-100 | |

Reeds Wood shingles Green roofs Glass | 45 45 1.4 2 | 50-100 25-35 500-2000 400-600 |

Roof covering material | Min. roof pitch [ ° ] | Approx. areal weight [N/m2] |

Clay roof tiles – pantile with mortar bedding Clay roof tiles – pantile with underlayment | 40 20 | 450 450 |

Clay roof tiles – interlocking with mortar bedding Clay roof tiles – interlocking with underlayment | 35 15 | 450 450 |

Concrete roof tiles Concrete roof tiles with underlayment Concrete roof tiles with interlocking sealing strips | 45 15 20 | 300 300 380 |

Slate (cement-based) with slate sealant Slate (cement-based) with underlayment Slate (cement-based) laid diagonally with underlayment Slate (natural) with underlayment | 34 18 18 20 | 200 200 200 400 |

Corrugated sheets (cement-based) with sealing strips in horizontal lap joints Corrugated sheets (cement-based) with underlayment Bituminous felt Roofing foil Metal (lengths which are joined on-site, e.g., zinc and copper) with sealant in grooves Metal sheets (prefabricated, factory-coated sheets) | 14 8 | 180 180 |

1.4 1.4 | 100 20-30 | |

3 10 | 20-100 20-100 | |

Reeds Wood shingles Green roofs Glass | 45 45 1.4 2 | 50-100 25-35 500-2000 400-600 |

Roof covering material | Min. roof pitch [ ° ] | Approx. areal weight [N/m2] |

Clay roof tiles – pantile with mortar bedding Clay roof tiles – pantile with underlayment | 40 20 | 450 450 |

Clay roof tiles – interlocking with mortar bedding Clay roof tiles – interlocking with underlayment | 35 15 | 450 450 |

Concrete roof tiles Concrete roof tiles with underlayment Concrete roof tiles with interlocking sealing strips | 45 15 20 | 300 300 380 |

5.2 Roof Tiles

Roof tiles are made of clay or concrete. Several types of roof tile exist, of which pantiles and interlocking tiles are the most common. Other, less common tiles exist such as shingles, Roman tiles, and convex and concave tiles.

There are several subtypes within each tile type and specially made tiles are available for each category, including ridge tiles, double pantiles, verge tiles, and vent tiles. There is a wide array of accessories in the form of clips, eave tiles, roll-fix ridge or hip ventilation strips, etc.

Tightness in tiled roofs is achieved with simple lap joints or overlaps between individual tiles. To ensure watertightness, an underlayment is typically fitted, supplemented by mortar bedding or sealing strips in the lap joints (see Table 17).

Tiled roofs are usually classed as heavy-weight roofs (see Section 5.1.3, Roof Pitch and Areal Weight).

Fire-Rating Roof Tiles

In terms of fire performance, roof tiles of both clay and concrete are pre-approved as BROOF(t2) (i.e., they do not contribute to fire) (The Commission, 2000) (see Section 2.5.1, Fire from the Outside).

5.2.1 Clay Roof Tiles

Clay roof tiles are shaped by pugged clay which is then dried and fired at approx. 1000 ° C. This gives a robust and frost-resistant tile.

Pantiles are traditional clay roof tiles. They have a simple smooth shape with mitred corners and lugs on the underside for hooking the tile to an underlay of roof battens (see Figure 64).

Pantiles are manufactured by extrusion, where the clay is pushed out through a nozzle whose opening is shaped like the cross section of the pantile. The clay is then cut to lengths corresponding to a tile and the corners are mitred.

Figur 64. Example of clay pantile where watertightness is secured with a simple lap joint.

Interlocking roof tiles are produced in a roof tile press where the clay is placed between two semi-moulds and pressed together until the desired shape is produced. Interlocking ribs along the top and side are used to install the tiles in a tight fit. Interlocking roof tiles are produced with a geometry corresponding to that of concrete roof tiles (see Figure 65).

Clay roof tiles are produced in a variety of colours, commonly red, black, yellow, greyish-blue, and brown, and have many types of coating. The colours are the result of the chemical composition of the clay but can also be altered by different manufacturing methods (e.g., by firing the clay tiles without oxygen supply).

A clay roof tile without surface treatment is water-permeable with a matt appearance.

The surface of clay roof tiles is usually coated with coloured or colourless engobe or glaze, giving the roof tile a denser and smoother surface.

The process of engobing allows finely grained clay minerals to be fixed to the surface during firing.

Engobed roof tiles are available in a variety of finishes, from a relatively water-permeable dull finish to a less water-permeable silky finish.

The process of glazing allows a mixture of quartz to be fixed to the surface during firing. Glazed roof tiles have a water-impermeable lustrous finish.

Applicable Standards for Clay Roof Tiles

Table 18 lists the standards applicable to clay roof tiles. The test results must comply with the requirements of DS/EN 1304, Clay roofing tiles and fittings – Product definitions and specifications (Danish Standards, 2013l). A newer version of this standard appeared in 2013, but has not yet been harmonised (Danish Standards, 2013d).

Clay roof tile tolerances are assessed based on the measurements of ten tiles. The mean value of the length and width of the tiles must be within ± 2% of the declared value. As for torsion, the mean value must be within ± 1.5% of the total length plus width.

Table 18. Overview of test standards for clay roof tiles.

Parameter | No. | Standard |

|---|---|---|

Flexural strength | DS/EN 538 | Clay roofing tiles for discontinuous laying - Flexural strength test (Danish Standards, 1994) |

Water-permeability | DS/EN 539-1 | Clay roofing tiles for discontinuous laying - Determination of physical characteristics - Part 1: Impermeability test (Danish Standards, 2006) |

Frost-resistance | DS/EN 539-2 | Clay roofing tiles for discontinuous laying - Determination of physical characteristics - Part 2: Test for frost resistance (Danish Standards, 2006) (Danish Standards, 2013e) |

Geometric characteristics | DS/EN 1024 | Clay roofing tiles for discontinuous laying - Determination of geometric characteristics (Danish Standards, 2012b) |

5.2.2 Concrete Roof Tiles

Concrete roof tiles are made of concrete with and admixture of sifted aggregate. The tiles are cast in metal moulds and are uniform and dimensionally stable.

The dimension and shape of concrete roof tiles are roughly the same as clay tiles and they are often produced as interlocking tiles. Contrary to interlocking clay tiles, interlocking concrete tiles do not have top and bottom ribs. Concrete roof tiles are often colour-through and surface-treated. They are typically black, slate, coral, and brown in colour.

Concrete roof tiles are installed in the same way as clay tiles (i.e., usually with an underlayment). As concrete roof tiles are relatively dimensionally stable, the specifications for batten spacing supplied by the manufacturer are extremely reliable

Applicable Standards for Concrete Roof Tiles

Concrete roof tiles are subject to the standard DS/EN 490, Concrete roofing tiles and fittings for roof covering and wall cladding - Product specifications (Danish Standards, 2011b). The testing of flexural strength, water permeability, frost resistance, and geometric characteristics is performed according to DS/EN 491, Concrete roofing tiles and fittings for roof covering and wall cladding - Test methods (Danish Standards, 2011c).

Figure 65. Example of a concrete roof tile where the ribbed profile on the long side helps to keep the structure watertight.

5.2.3 Constructing a Tiled Roof

Tiled roofs are subject to requirements regarding minimum roof pitch. This depends on the specific type of roof tile used (especially whether they are pantiles or interlocking tiles) and whether the assembly includes underlayment or not.

Tiled roofs with underlayment are suitable for roof pitches down to slopes of 15–25 ° depending on the material and design of the tiles. In each case, manufacturer instructions must be followed carefully. The max. roof slope is normally 85 °. Certain types of roof tile are suitable for use on vertical surfaces.

Tiled roofs can be constructed using mortar bedding instead of underlayment. If mortar bedding is used, interlocking roof tiles can be used for roof pitches down to 35 ° and pantiles for pitches of 40 °. Tiles are available for roofs with even shallower pitches. Some brands of concrete roof tile allow tiles to be used with mortar bedding down to a slope of 20 °. If the mortar bedding is executed carefully, it will contribute to keeping the roof watertight for many years to come. However, the mortar bedding should be checked approx. every five years to ensure adequate coverage and adhesion. For roof surfaces that are inaccessible from the inside (such as couple roofs and sloping walls in unutilised loft spaces) mortar bedding should not be used due to the difficulty of checking and maintaining it.

Concrete roof tiles with sealing strips incorporated into the joints can also be used without underlayment down to a slope of 20 °.

Table 17 provides an overview of roof tiles and min. slope requirements.

The construction of tiled roofs is, in principle, identical for clay and concrete roof tiles.

Roof tiles are typically laid on a supporting structure of timber rafters (e.g., attic or lattice trusses).

In addition to the actual roof tile, the following elements are normally used for a tiled roof:

- Underlayment

- Spacer bars

- Tile battens

- Tile clips

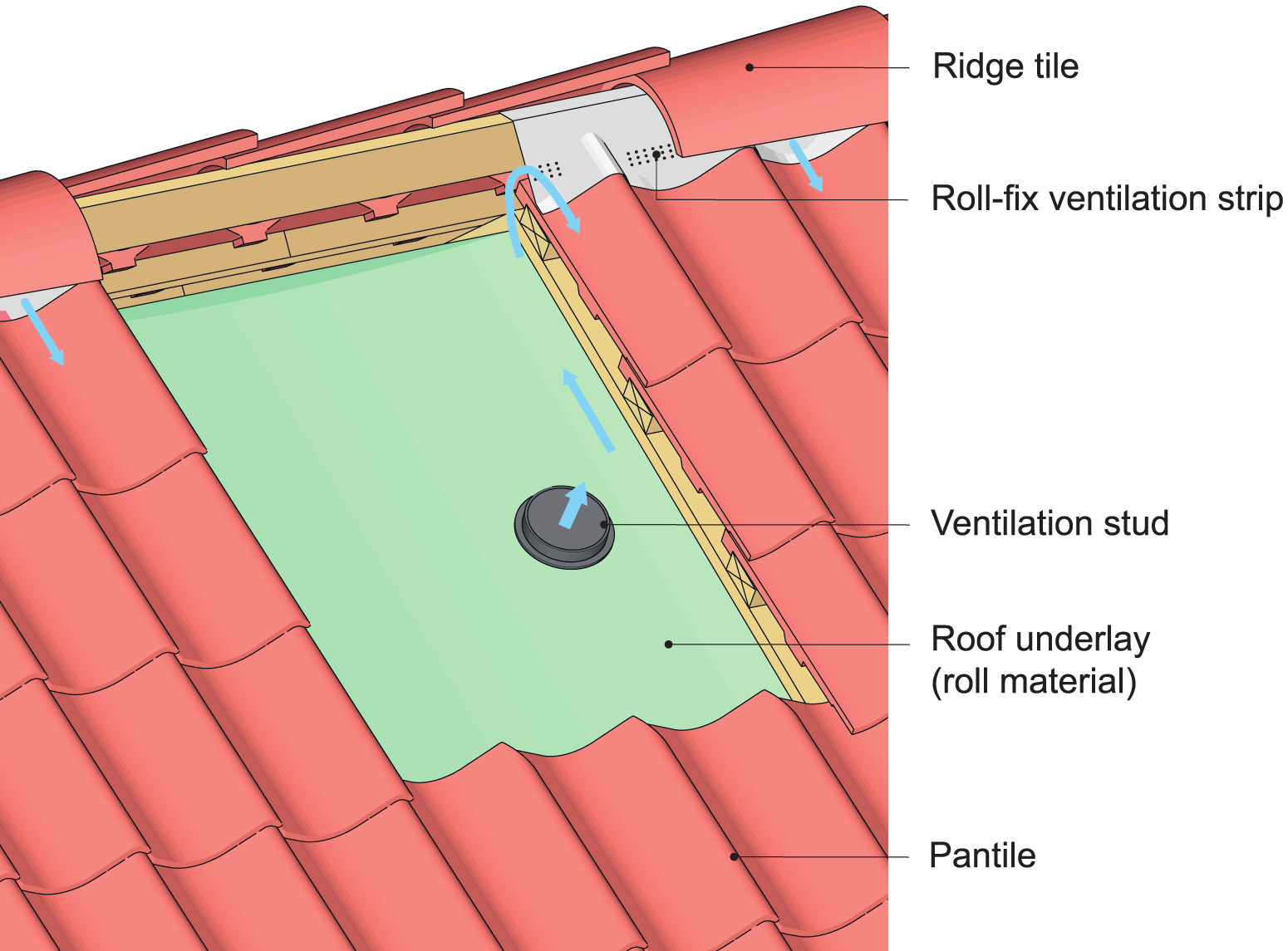

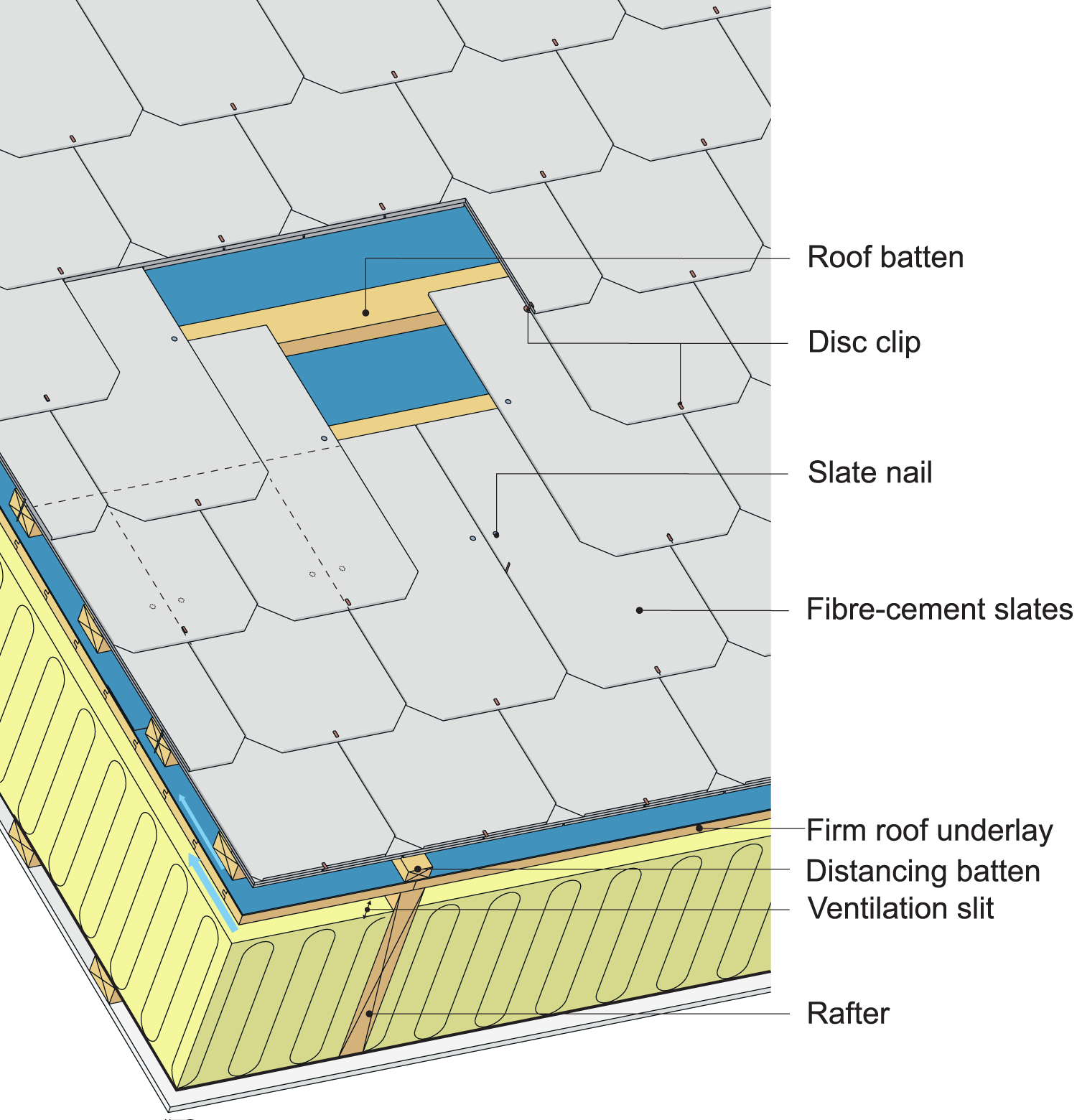

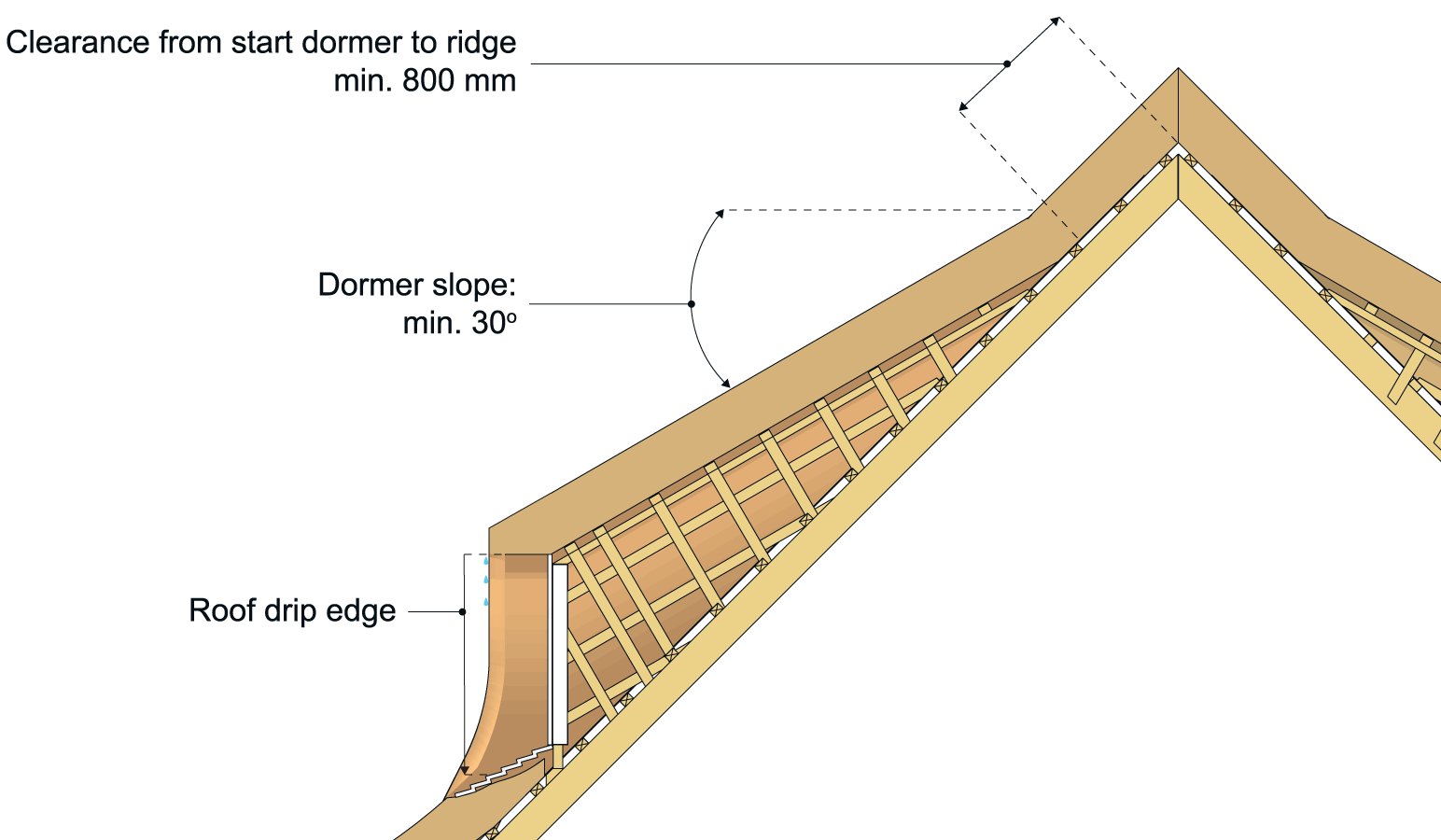

Figures 66 and 67 are examples of tiled roof assemblies.

Figure 66. Example of a roof assembly with a pantile roof covering on a vented firm underlayment.

Figure 67. An example of a roof assembly with a covering of concrete roof tiles on a vented firm underlayment.

Underlayment

Requirements for underlayment (including ventilation) are outlined in Section 3, Roofing Underlayment.

Spacer Bars

Spacer bars are used in roofs with underlayment for the following purposes:

- To raise the roof battens to enable water and dirt to pass under the battens

- To ensure that the underlayment is securely fixed

- To ensure adequate ventilation on the underside of the roof covering in conjunction with air intake at eaves and exhaust at ridge.

Furthermore, the spacer bar leaves room for mechanical fixing to keep the roof tiles in place.

For a detailed description of issues concerning spacer bars, see Section 3.1.2, Spacer Bars.

Roof Battens

Rules and guidelines concerning roof battens are listed in Section 2.6.1, Roof Battens. For a detailed description, see TRÆ 65 (Træinfomation, 2011).

Most manufacturers of roof tiles will indicate the batten spacing required for specific roof tiles. Battens are usually spaced at around 300 mm. Sometimes a trial installation of the specific roof tiles is carried out to determine the batten spacing. This necessitates that all tiles be supplied from the same batch and delivered at the same time.

The battens are installed with a lathing tolerance of ± 3 mm measured across the rafters. Tolerances must not accumulate in the assembly.

Mechanical Fixings

Tile clips are used to fix tiles to the battens. Individual types of tile clips must carry a label indicating the type of tile and batten dimension they are compatible with because they are produced specifically for the combination of roof tile and batten dimensions. Tile clips are supplied with roof tiles. Clips for interlocking roof tiles are available as head clips and tail clips (see Figure 68). For pantiles, specific clips and clamps are available (see Figure 64).

Clips must be weatherproof and corrosion resistant. Tile clips are typically made from stainless steel or from aluminium and zinc alloys.

The resistance of tile clips to wind suction is tested according to DS/EN 14437, Determination of the uplift resistance of installed clay or concrete tiles for roofing - Roof system test method (Danish Standards, 2005c).

The application of mechanical fixings is also covered in Section 5.2.5, Installing a Tiled Roof.

Figure 68. Head and tail clips for hooking roof tiles to roof battens.

5.2.4 Venting Tiled Roofs

Tiled roofs must be vented on the underside of the tiles to minimise the risk of excessive moisture content in the tiles, potentially leading to frost damage. If a vented underlayment is used, additional ventilation between underlayment and thermal insulation layer must be established.

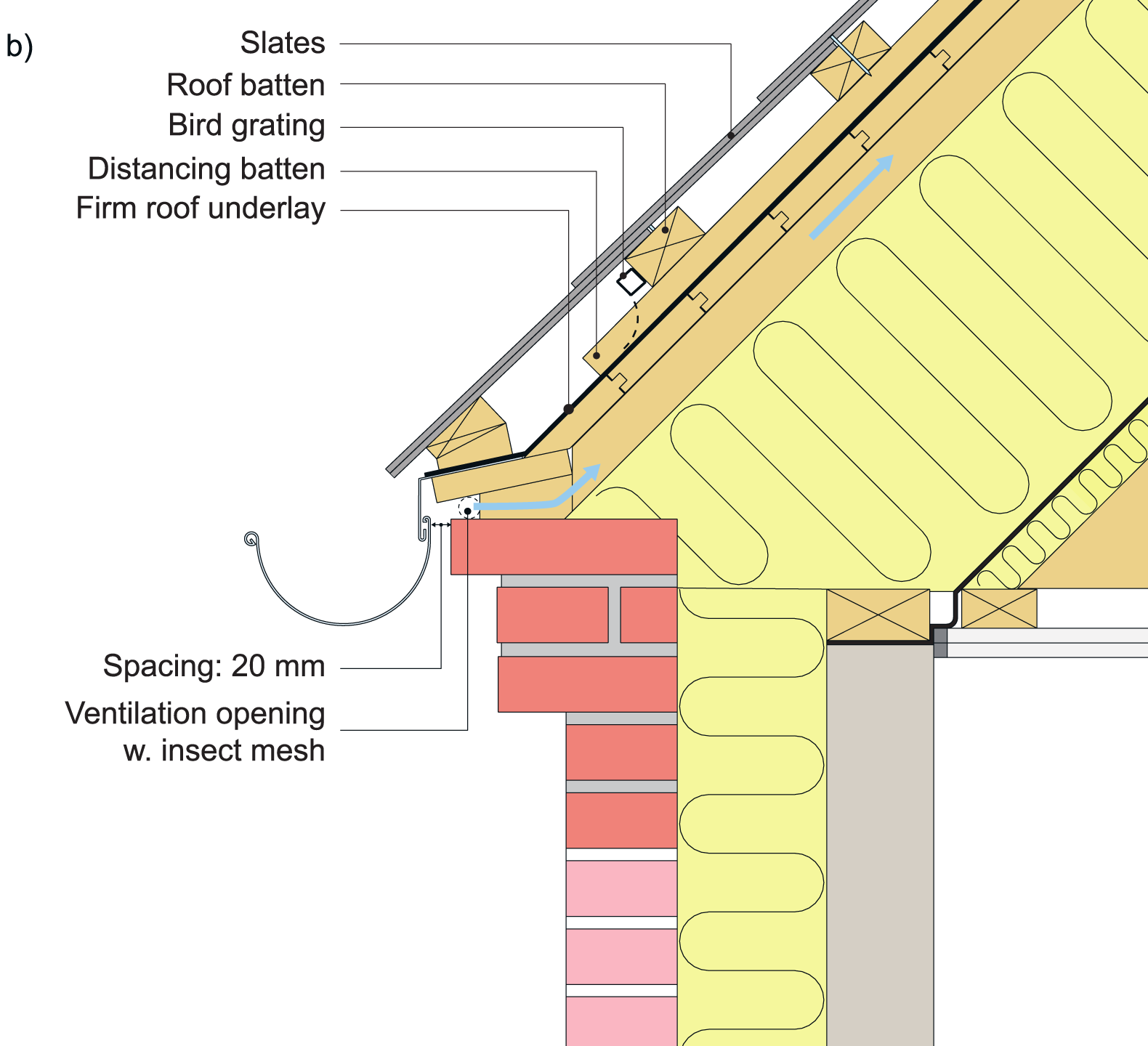

Ventilation of tiled roofs is typically achieved with vent openings at the eaves and ridges.

Tiled roofs require the size of the vent opening to be at least 200 cm2 per linear metre at the eaves and at least 100 cm2 per linear meter at the ridges, valleys, and hips to ensure adequate ventilation on the underside of the roof tiles. For houses up to 12 metres in height, there must be a continuous vent space below the roof tiles of at least 200 cm2 per linear metre.

To achieve an adequate vent space at the eaves and to prevent insects or animals from entering, an insect mesh or bird grating with an integrated ventilation unit fitted to the bottom should be installed (see Figure 69a). Special clamps for affixing bird gratings are available which avoid perforation of the underlayment during installation. Similarly a vent space area must be installed at ridges, valleys, and hips to ensure adequate venting of the underside of the roof tiles. At ridges and hips, a roll-fix ventilation strip in the form of flexible flashing material with perforations is often fitted. This prevents the ingress of vermin and rain and reduces the exposure of the underlayment to UV radiation (see Figure 69b).

Concrete roof tiles are not subject to the same under-tile ventilation required for clay tiles. At the eaves, therefore, an ordinary bird grating without a ventilation unit can be used. In each case, the manufacturer’s instructions for venting the underside of the roof tiles must be followed.

General guidelines for roof ventilation are outlined in Section 2.3, Roof Ventilation.

Figure 69. The underside of clay roof tiles must be vented to prevent moisture levels in the tiles from rising as this can lead to frost damage. Vermin must also be prevented from entering the roof assembly.

- Example of a vent opening at the eaves using a vented bird grating (shown here anchored by a bird grating clamp to avoid perforation of the underlayment).

- Example of vent opening at the ridge using a ridge ventilation strip (see Figures 72–74.

5.2.5 Installing a Tiled Roof

Before laying the roof tiles, attention should be given to the following special focus areas by checking the following:

- The net coverage per tile. This should be tested with a trial installation, including testing whether tile net coverage is consistent with the total width of the roof surface. It may be necessary to adjust the design by adapting the width of the overhang.

- The squareness of roof surfaces. This can be tested by plotting the angle using a 3-4-5 triangle or by examining whether the diagonals on the roof surface are consistent with the length of the roof surface at eaves and ridges.

- The spacing of battens is correct for the tiles used according to information supplied by the manufacturer (or determined through trial installation).

- The underlayment is correctly installed, is watertight, and undamaged.

- The underlayment can be carried over the full height of the barge board (if relevant).

- The spacer bars are at least 25 mm thick and made of pressure-impregnated timber (or similar).

Laying the Roof Tiles

Roof tiles are laid on roof battens, spaced according to manufacturer’s instructions or determined following a trial installation. Trial installations are recommended for clay tiles, but unnecessary for concrete tiles, as these are more dimensionally stable. The length and width of the roof surface should be adapted to fit the chosen roof tiles at the design stage to avoid cutting, if possible. For gable ends where verge tiles or double pantiles are used, cutting is not an option. If required, tiles can be adapted to the length or height of the roof surface by cutting the top layer. If the top layer of roof tiles is cut, the tiles must be fixed below the overlap with stainless steel washer-head screws.

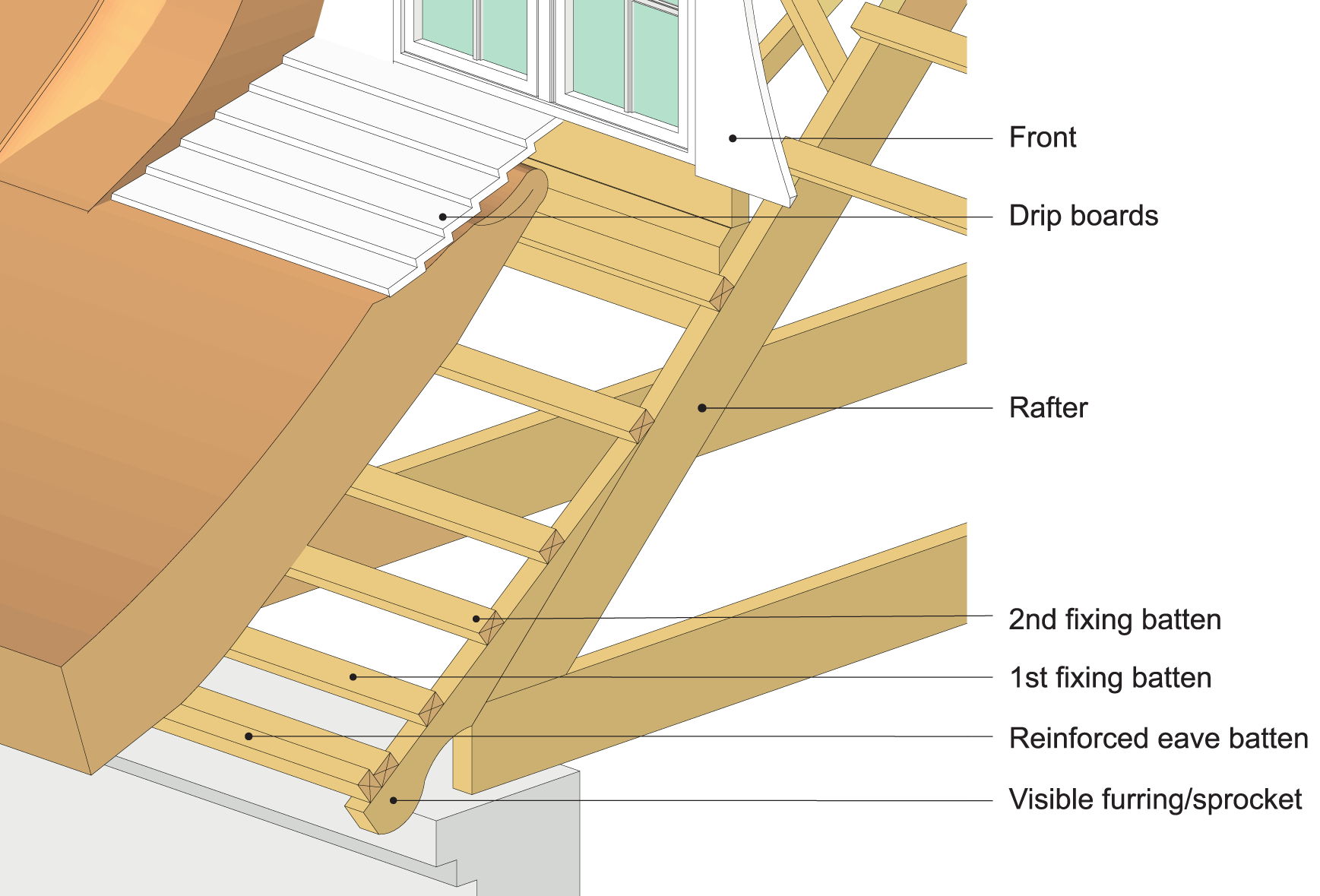

The bottom row of battens is installed so that the roof tiles will project 30–40 mm into the gutter (measured horizontally). Based on this first row of battens, the position of the remaining battens is plotted with the spacing indicated or determined so that the distance between roof ridge and upper edge of the top batten complies with the measurement stated by the manufacturer. Further information on trial installations and positioning of battens is available in Tegl 36, Oplægning af tegltage (Installing Tiled Roofs) (MURO, 2005 [under revision, ed.]).

Before lifting the tiles onto the battens, the position of every third tile should be plotted on the battens, or as instructed by the manufacturer’s installation manual.

The tiles are laid from right to left as follows:

- Installation should start in the lower right corner and finish at the top left corner. Once the first row has been laid, the following should be checked:

- The tiles have the required overhang (for double pantiles) of approx. 30 mm at gable ends after fitting barge board

- The distance between the ‘wrap’ over the edge and gable end is approx. 10 mm if using verge tiles.

- The tiles project correctly into the gutter.

- Having laid three vertical rows of roof tiles to the ridge, check that the roof tiles are placed evenly above one another.

- The top layer should be laid along the ridge and adjusted as described for the bottom layer.

- The rest of the roof tiles should then be laid, starting from below and proceeding up the roof. Every third row should be checked with a smoothing board for example, according to the markings on the tile battens. The tolerance should be ± 2 mm measured across an average of 10 roof tiles.

For interlocking roof tiles, the grooves must click into place tightly like tongue-and-groove joints. This ensures a tight and stable roof surface. Pantiles must be placed closely together, and the mitred corners should be kept as small as possible.

Fixing Roof Tiles

Roof tiles are fixed as they are laid.

For clay roof tiles, at least every second roof tile is mechanically fixed in diagonal rows (see Figure 70). For concrete tiles, typically only every third tile is fixed. All perimeter roof tiles must be mechanically fixed, including the bottom or second lowest horizontal row, the top row (by the ridge), the perimeter row (by the gable ends), and all tiles along valleys, roof lights, and penetrations in the roof surface.

We recommend that designers assess whether to increase the extent of mechanical fixings relative to location (terrain category), the form, prevailing winds, and turbulence conditions in exposed locations. Examples of particularly exposed locations are:

- Inshore areas

- Areas classed as terrain category I and II according to Eurocode 1, Parts 1–4, General actions – Wind actions (Danish Standards, 2007c).

- Isolated tall buildings (three storeys and more)

- At the end of a street with tall buildings on either side, forming a wind tunnel (wind tunnel effect).

Figure 70. For clay roof tiles, at least every second tile is mechanically fixed in diagonal rows (marked in dark red) as well as all perimeter tiles (at ridges and eaves and all tiles near penetrations such as roof lights, etc.). Diagonal fixing of tiles ensures that individual tiles are fixed to the roof surface. For concrete tiles, normal practice is to fix every third tile.

For clay tile roofs in particularly exposed locations, all roof tiles must be mechanically fixed while manufacturers of concrete tiles often specify mechanical fixing of every second roof tile.

In special cases, it will not be sufficient to fix the roof tiles to the tile battens (e.g., for mansard roofs and other steep-pitched roofs of more than 60 °). In these cases all tiles must be fixed using stainless steel screws in addition to tile clips.

Special tiles are often fixed to ridges and hips is using special fixtures available from the manufacturer. Fragments of cut roof tiles from hips and valleys for example, can be bonded to the affixed neighbouring tile. For interlocking roof tiles, the groove must be fully bonded to avoid water-damming and overflow

5.2.6 Details – Roof Tiles

This section shows examples of typical detail design used in tiled roofs. See installation instructions and further details from manufacturers.

In detail design, it is necessary to take general guidelines for several issues into account (e.g., guidelines concerning ventilation and Building Regulations provisions relative to fire safety and thermal insulation). General issues concerning the choice of roof are outlined in Section 1.1, Roof Design.

For further examples of roof detail design, see Section 6, Dormers, Roof Lights, and Skylights; Section 7, Flashings – Penetrations and Intersections; and Section 9, List of Examples.

Valleys

Two types of valley constructions exist: a raised (ordinary) valley (which is mounted on top of the rafters) and a concealed valley (where the valley underlay is flush with the upper side of the rafters). The latter is usually considered the most reliable. The width of the valley is determined by the roof pitch, so that the height from the lower to the upper part of the valley is at least 100 mm (i.e., the shallower the pitch, the wider the valley).

Figure 71 shows an example of a concealed valley design in a roof with a vented loft space and a tiled roof with roll-material roofing underlayment.

For a detailed description and further examples of valley designs, see Section 7.2.4, Valleys.

Figure 71. Example of zinc valley design in tiled roof with a vented loft space and roll-material roofing underlayment. The zinc is installed on a firm deck recessed relative to the jack rafters, so that the upper side of the decking is flush with the upper side of the rafters. The zinc extends 400-450 mm to either side relative to roof pitch. The height from the bottom of the valley to the upper edge of the zinc must be at least 100 mm (see Section 7.2.4, Valleys). The decking under the zinc is adjusted to ensure that the zinc is fully supported. If sheeting such as plywood is used, a structured mat should be fitted underneath the zinc. The underlayment and zinc overlap by at least 150 mm and is bonded to the zinc (e.g., with one, or even two, sealant strips of butyl tape).

Vented Ridge

Figure 72. Example of vented ridge design in tiled roof with vented roll-material roofing underlayment. Venting the underlayment is done via roof vents for each roof truss placed close to rafters to prevent water ingress from above. The ridge is vented by a roll-fix ventilation strip under the ridge tiles (see Figure 74).

Figure 73. Example of vented ridge in a tiled roof with roll-material roofing underlayment (see Figure 72). The underlayment is vented via roof vents for each roof truss placed close to rafters to prevent water ingress from above. The ridge is vented by a roll-fix ventilation strip under the ridge tiles. The roll-fix ventilation strip also prevents ingress of birds and insects into the roof assembly.

Figure 74. Example of vented ridge in tiled roof with a firm underlayment. The underlayment is vented via one roof vent placed near the ridge for each roof truss. The ridge is vented via a roll-fix ventilation strip under the ridge tiles.

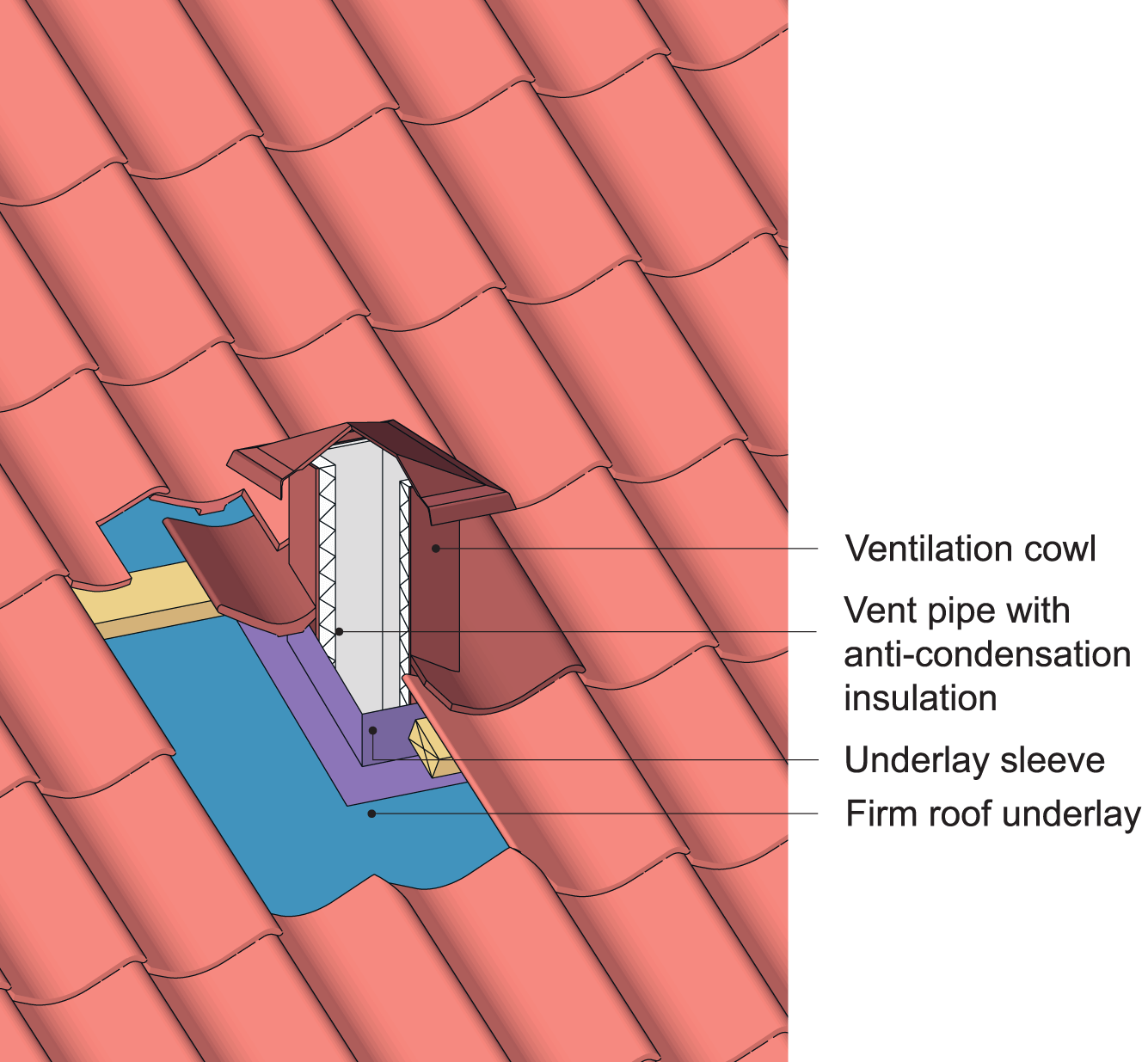

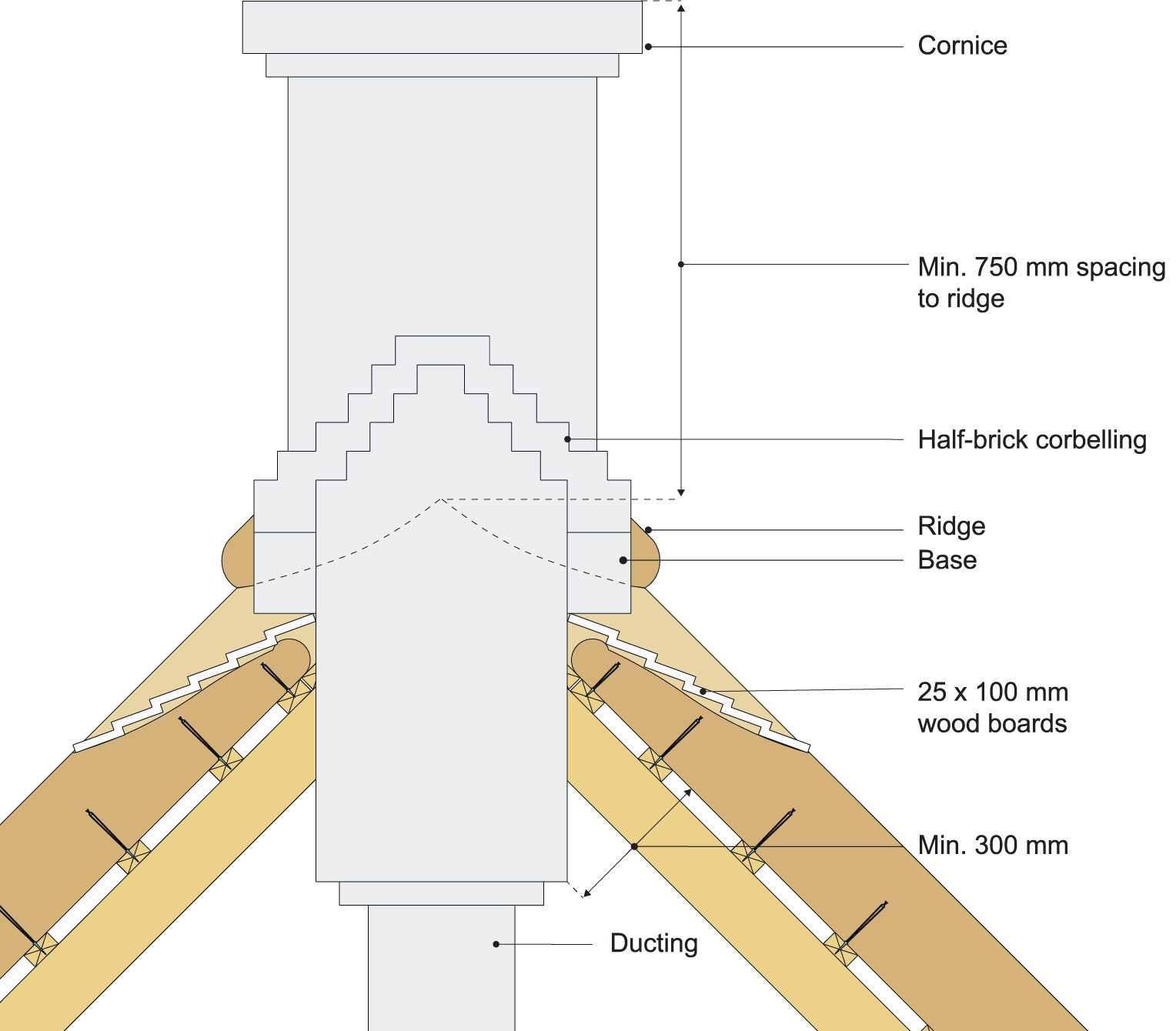

Ventilation Duct Penetration

Figure 75. Example of roof vent cowl penetration with pre-mounted flange adapted to the shape of the roof tiles. It is joined to the underlayment is done on a firm underlay, in this example, firm underlayment (see Figure 198).

5.3 Roof Sheets – Corrugated Fibre-Cement Sheets

Roof sheets are usually made of cement-based materials reinforced with synthetic fibres and cellulose. The sheets are thin (approx. 6 mm) and are reinforced by their corrugated shape and the synthetic fibres. Most sheets are supplied with integral strips acting as a substitute walk-proof underlay on the finished roof covering.

The tightness of corrugated sheet roofs is achieved by simple overlap or lap joints between sheets combined with sealing strips integrated into the horizontal lap joints. Typically, no underlayment is installed.

Corrugated fibre-cement sheets belong to the category of light-weight roofs, see Section 5.1.3, Roof pitch and areal weight.

Fire-Rating Corrugated Fibre-Cement Sheets

In terms of fire performance, corrugated fibre-cement sheets are pre-approved as BROOF(t2), i.e., they do not contribute to fire (The EU Commission, 2000), see Section 2.5.1, Fire from the outside.

Applicable Standards for Corrugated fibre-Cement Sheets

Corrugated sheets are subject to the standard DS/EN 494, Fibre-cement profiled sheets and fittings - Product specification and test method (Danish Standards, 2012c).

5.3.1 Types of Corrugated Sheets

Corrugated fibre-cement sheets are available in several sizes with different profiles (see Table 19). The choice of size and profile for a specific project is determined by aesthetic or functional requirements. The roof sheets come with a wide choice of accessories, including accessories for finishes around ridges, barge boards, and roof penetrations.

The watertightness of corrugated sheets is achieved with horizontal and vertical overlaps supplemented by sealing strips. To ensure an efficient lap joint, the last corrugation crest is slightly lower than the others (see Figure 76).

Corrugated sheets are available untreated or with a coloured surface treatment (e.g., red or black).

Corrugated sheets without surface treatment are water-permeable and have a grey, matt surface.

Table 19. Typical properties of corrugated sheets in large and small formats. For large-sized sheets, one or two additional battens are often installed, but this number can be altered depending on whether a walk-proof decking or a batten dimension larger than 38 × 73 mm is used, as instructed by the manufacturer.

Type/Size | Approx. 1200 × 1000 mm | Ca. 600 × 1000 mm |

|---|---|---|

Weight/item | 14-19 kg | 8-9 kg |

Material use/m2 | Approx. 1 | Approx. 2 |

Batten spacing | 1070 mm | 460 mm |

Additional battens | 1-2 | 0 |

Figure 76. Example of fibre-cement roof sheet with a corrugated profile. Corrugated fibre-cement sheets are available both as full-edged and mitred relative to their position on the roof surface.

5.3.2 Constructing a Roof Using Corrugated Fibre-Cement Sheets

Corrugated sheets can be used for pitches down to approx. 14 °. For shallower pitches or exposed locations, joint sealant strips can be fitted horizontally and in vertical lap joints as an extra precaution.

Some manufacturers allow the use of their corrugated sheets down to an 8 ° roof pitch with underlayment. However, pitches below 14 ° can make installing effective eaves challenging (particularly water drainage from the underlayment) and can make it difficult to achieve a stack effect for sufficient ventilation. Where applicable, endorsement from the underlayment manufacturer must be sought for such shallow pitches.

Table 17 shows corrugated fibre-cement sheet types and minimum roof pitch requirements.

Corrugated sheets are laid on a supporting structure of wooden rafters or purlins.

In addition to the corrugated sheets, the following elements are used for a roof covering applications using corrugated sheets:

- Underlayment (if required)

- Spacer bars (when using underlayment)

- Battens or purlins

- Screws for fixing materials to the structure

- Sealant strips

- Walk-proof decking (if required)

Corrugated fibre-cement sheet roof coverings must be vented according to applicable guidelines (cf. Section 2.3.3, Guidelines for Ventilation of Pitched Roofs). Eave ventilation is usually achieved with vent openings, a fitted insect mesh or bird grating, and cowls or ridge solutions at ridge level with integral ventilation solutions.

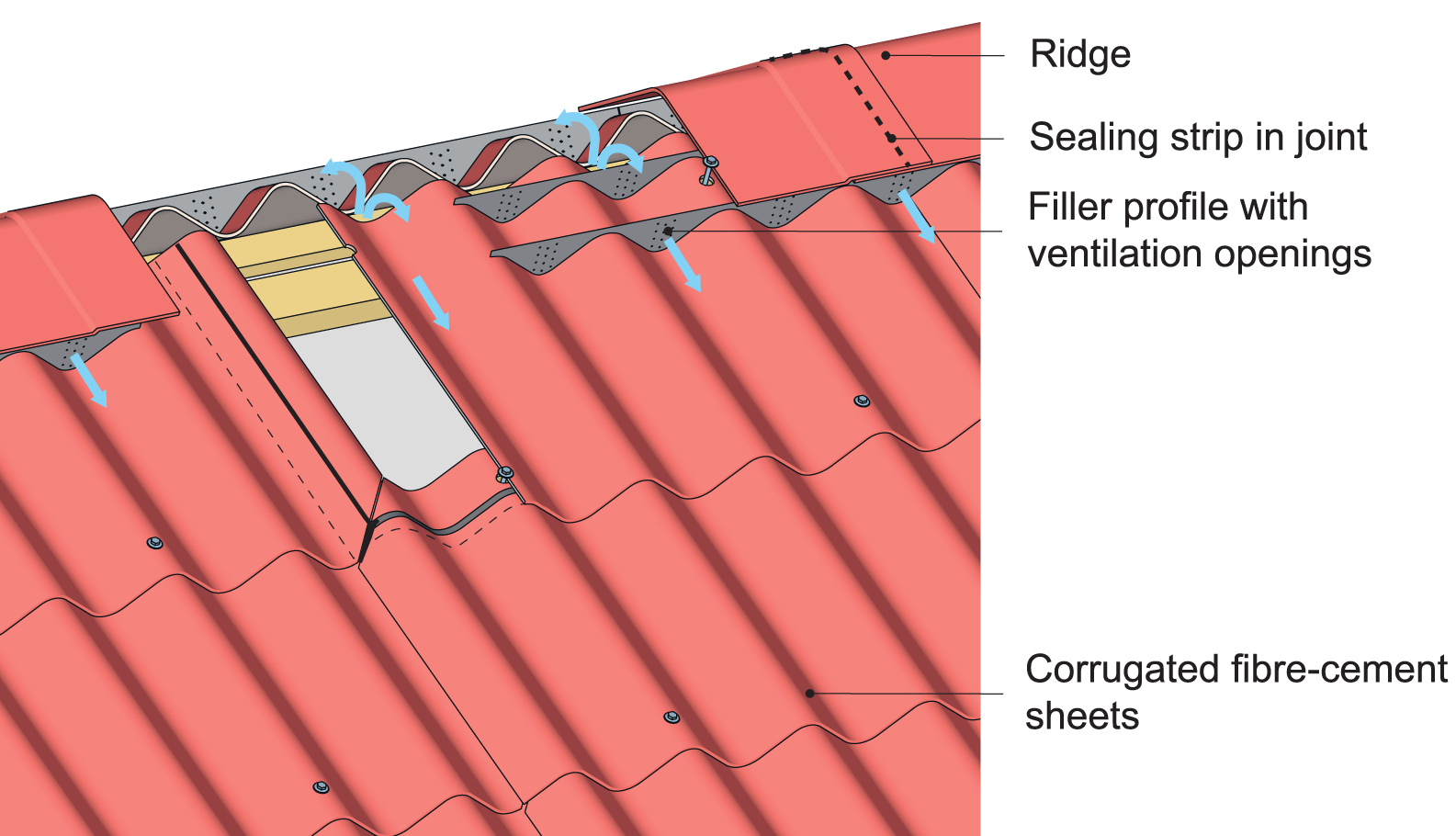

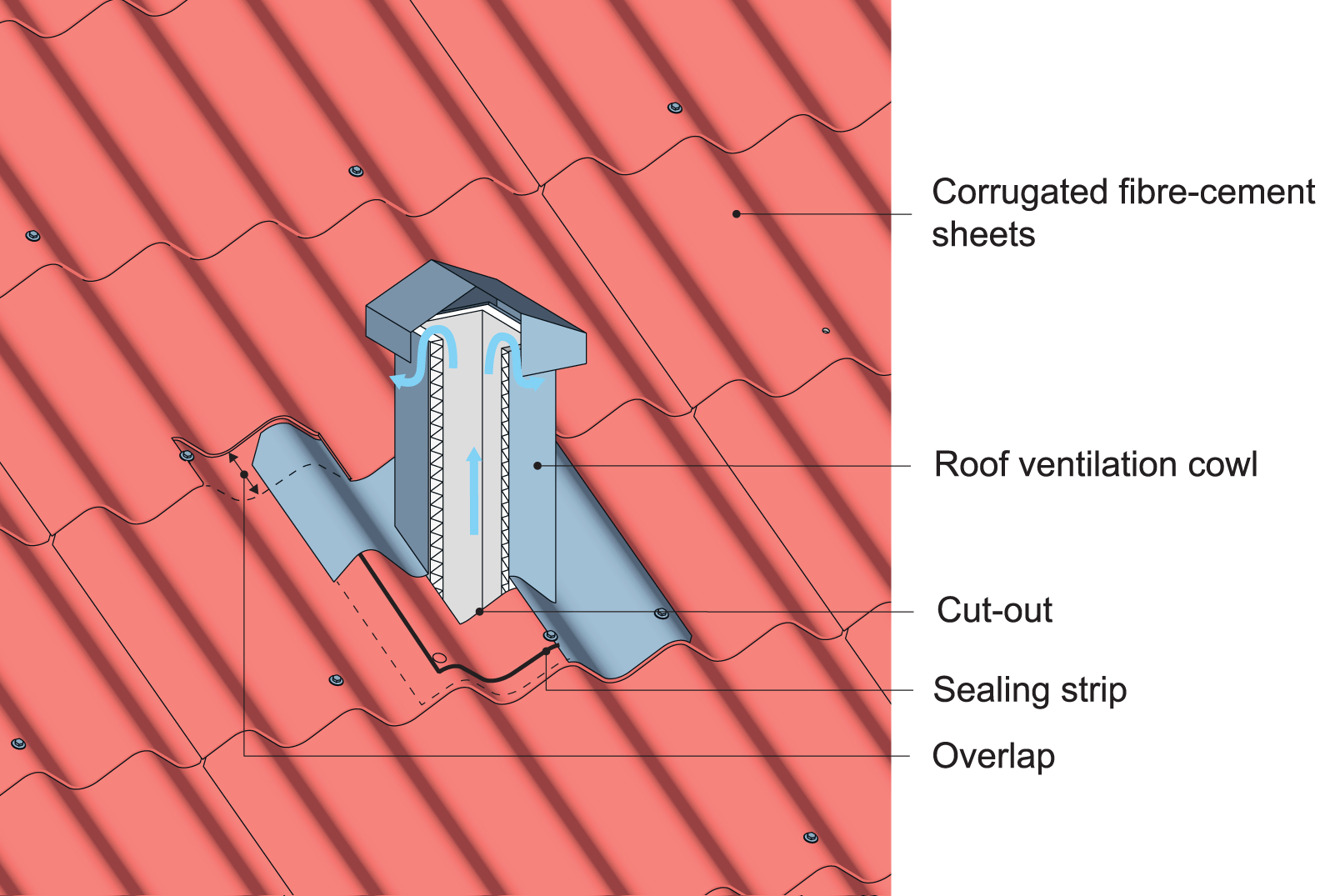

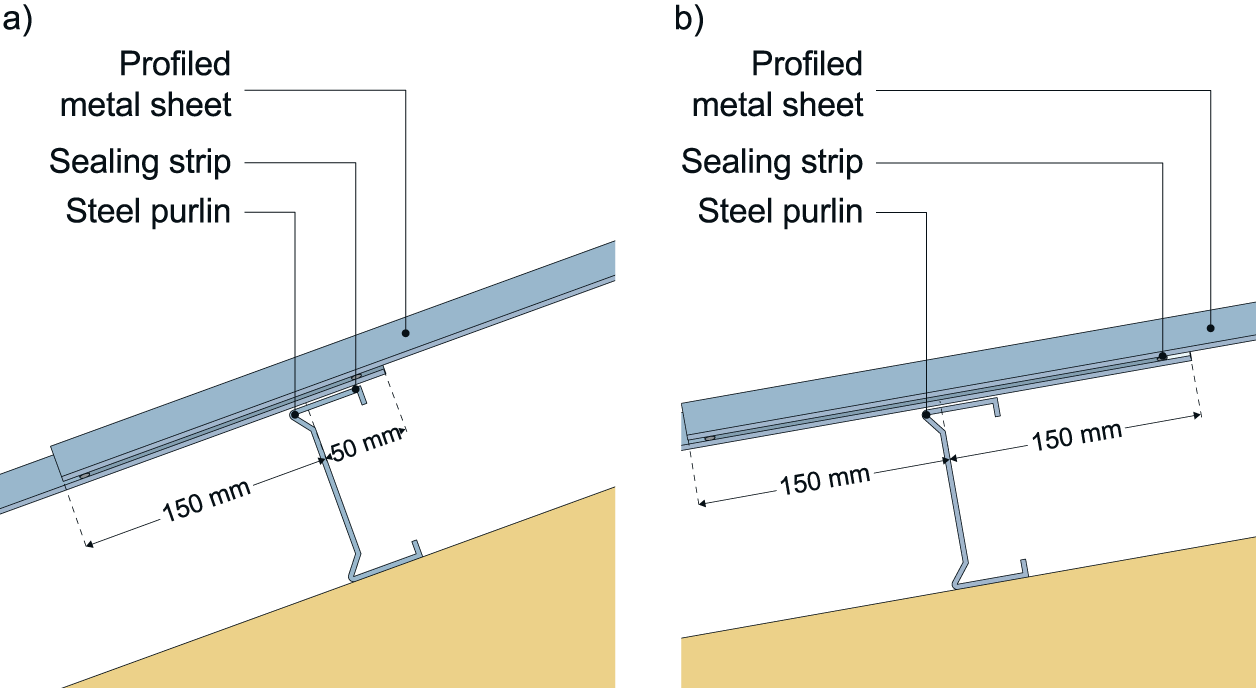

Figures 77 and 78 show examples of roof covering assemblies using corrugated fibre-cement sheets.

Figure 77. Example of roof covering of corrugated fibre-cement sheets on lattice-trussed roof assembly with battens and a vented loft space. For batten spacing exceeding 460 mm, a fall arrest system must be established (The Danish Work Environment Authority, 2014).

Figure 78. Example of a corrugated fibre-cement sheet roof covering on a couple roof with vented roll-material roofing underlayment.

Underlayment

Corrugated sheets can be installed with or without underlayment. If no underlayment is used, watertightness must be ensured by using sealing strips in the lap joints between sheets (see Figure 77 and the following section Sealing Strips).

Some manufacturers specify the use of underlayment for very shallow pitches. In such cases, manufacturer’s installation instructions must be carefully observed, including ensuring that it is feasible to use the underlayment for the shallow pitch required.

Issues concerning requirements relative to underlayment, including venting the underlayment, are outlined in Section 3, Roofing Underlayment.

Spacer Bars

Spacer bars are used for roofs with underlayment to:

- Raise the battens, allowing water and dirt to pass underneath

- Ensure that the underlayment is fixed securely

- Ensure adequate ventilation on the underside of the roof covering in conjunction with air-intake at the eaves and exhaust at the ridge

Issues concerning spacer bars are outlined in detail in Section 3.1.2, Spacer Bars.

Battens or Purlins

Corrugated sheets are laid and fixed to battens or purlins. To secure the strength and stability of the assembly, strength-graded battens or purlins complying with strength grade C18 must be used (cf. DS/EN 14081-1 (Danish Standards, 2016c)). Rules and guidelines for roof battens are outlined in Section 2.6.1, Roof Battens. For rafter spacing exceeding 1000 mm measured from centre-to-centre (c.t.c.), the dimension of C18-labelled battens is specified in a batten table in TRÆ 65, Taglægter (Roof Battens) (Træinformation, 2011b).

The sizing of purlins is outlined in the report TRÆ-rapport no. 05, Beregning af tagåse (Calculating Timber Purlins) (Træinformation, 2015b).

Manufacturers will state the bearing length required for their corrugated sheets. This length is relative to the type and format of the sheet.

A tolerance of ± 3 mm measured across the rafters must be allowed when installing the battens (cf. www.tolerancer.dk and Træ 65, Taglægter (Roof Battens) (Træinformation, 2011b). Tolerances must not accumulate in the assembly. For purlin constructions, deviations can exceed this without causing problems with tightness or lifespan of the sheets.

Fixing the Sheets

Screws are used to fix corrugated sheets to battens or purlins (see Figure 79). The sheets are screwed down through the top of the corrugation crest and washer-head screws appropriate to the specific sheets are used. Sheets and screws should be supplied by the same manufacturer, which is the best way of ensuring compatibility.

Usually, two screws are used per sheet. For exposed locations, three screws should be used at roof edges.

Screws must be weather resistant to avoid corrosion.

Figure 79. The sheets are installed with sideward lap joints consistent with one whole corrugation crest. Sheets are screwed down with washer-head screws. Screws are always placed at the top of corrugation crests (see Figures 77 and 78).

Sealing Strips

Sealing strips are applied in the horizontal lap joints to ensure watertightness when installing corrugated sheets without roofing underlayment. Sealing strips are fitted at the same time as the sheets are installed. In this way, sealing strips are clamped and fixed in the lap joints.

For shallow pitches or exposed locations, joint sealant strips should also be fixed to the vertical lap joints (see Figures 77 and 80).

Figure 80. Corrugated sheets are usually sealed by fitting sealing strips to the horizontal lap joints. For exposed locations, additional sealing strips are fitted to the vertical joints.

Walk-Proof Underlay – Finished Roof

Where the c.t.c. spacing between battens exceeds 460 mm and the distance between roof surface and walk-proof underlay exceeds 2 metres, either a walk-proof underlay or sheets approved for use without walk-proof underlay must be installed (e.g., corrugated sheets with embedded strips) (cf. WEA Guideline 2.4.2) (Danish Working Environment Authority, 2014).

5.3.3 Installing a Roof Using Corrugated Fibre-Cement Sheets

Before installing the sheets, attention should be given to the following special focus areas by checking:

- The net coverage per tile. This can be checked with a trial installation, including whether the tile net coverage is consistent with the total width of the roof surface. Adjustments may be necessary to adapt the width of the overhang or using a verge profile

- That roof surfaces are square. This can be checked by examining whether the roof surface diagonals are consistently with the length of the roof surface at the eaves and ridge level

- That the spacing between supports is correct according to information supplied by the manufacturer

- That rafters and battens are square. When checking for this with a 2-metre smoothing board, deviations should be evenly distributed and be max. 15 mm

- That there is a space of at least 25 mm between the lower edge of the batten and the top of the insulation material, in assemblies where the thermal insulation is installed parallel to the sheets. For purlin assemblies, this is measured from the underside of the roof sheet (corrugation valley) and the upper side of the insulation material.

- That the roofing underlayment (if used) is laid correctly, tightly installed, and undamaged

- That the roofing underlayment can be brought over the full height of the barge board (if applicable)

- That spacer bars (at least 25 mm thick and made of pressure-impregnated timber) are installed between roofing underlayment and battens

Installing Corrugated Sheets

Corrugated sheets are installed on battens or purlins with the spacing specified by manufacturer or determined by a trial installation. The length and width of the roof surface should be adapted to the chosen corrugated sheets at the design stage to minimise cutting.

Sheets should be installed at right angles to the eaves. It is advisable to mark construction lines at right angles to the eaves. The first row of battens should be installed so that the roof sheets project 30–40 mm into the gutter measured horizontally and that this is consistent with the typical projection of sheets approx. 60 mm out from the underside of the lowermost batten.

Starting from the lowermost batten, the location of the rest of the battens or purlins should be marked according to the specified or determined spacing, so that the distance from the ridge to the upper side of the batten or purlin corresponds to the measurement supplied by the manufacturer.

Sheets (see Figure 81) are installed from left to right as follows:

- Laying should start at the lower left corner and finish at the top right corner. When the first row has been installed, one should check that the sheets have been positioned correctly at the gables (relative to the chosen solution) and that the sheets project out correctly in relation to the gutter.

- The remaining sheets should then be installed starting from below and moving up the roof. Check that the direction of laying is straight for every third row (for example, using a piece of string). Sheets should be installed by overlapping one corrugation crest in the vertical joints and a min. overlap of 110 mm in the horizontal joints.

Figure 81. A diagram of the installation of corrugated sheets. Corrugated sheets are installed starting in the lower left corner of the roof assembly. It is important to install the sheets at exact right angles to the eaves and it is a good idea to mark a row of vertical construction lines along the battens or purlins. All sheets must be mechanically fixed.

5.3.4 Details – Corrugated Fibre-Cement Sheets

This section shows examples of typical detail design in roof coverings of corrugated fibre-cement sheets. Manufacturer installation instructions and product details must also be consulted.

In the design of roof details, it is necessary to take general guidelines for several issues into account, including those concerning ventilation and building regulations for fire safety and thermal insulation. General issues concerning the choice of roof are outlined in Section 1.1, Roof Design.

For further examples of roof detail design, see Section 6, Dormers, Roof Lights, and Skylights, Section 7, Flashings – Penetrations and Intersections, and Section 9, List of Examples.

Eaves

At the eaves, it is vital that water is discharged into the gutter and equally important that the required vent openings are in place to ensure roof ventilation.

Figure 82. An example of an eave design using corrugated fibre-cement sheets without roofing underlayment. Boxed-in overhang with ventilation under the crests of fibre-cement sheets via special filler profile.

Ridge

Figure 83. An example of ridge design where venting is achieved with a special filler profile across the crests of the fibre-cement sheets. Ridge corrugation overlaps must be identical to the horizontal overlaps between individual sheets.

Chimney and Ventilation Penetrations

Figure 84. An example of roof vent cowl installation with pre-fitted flange. The flange is adapted to the shape of the corrugated sheets.

Valley

Figure 85. An example of closed valley design in corrugated fibre-cement sheets above vented loft space. The valley is installed on firm decking fitted to the rafters. The corrugated sheets should overlap the edge of the valley by at least 60 mm (see Section 7.2.4, Valleys).

5.4 Slate Roofs

Slate roofing is the term used for a roof covering of plane and thin roof tiles. The slates can either be made of natural rock (slate) or fibre-cement. Both types are available in relatively small sizes. Accessories in the form of slate hooks, nails, and vent strips are available for both types.

Slate tiles are installed by overlapping the individual slates. To ensure watertightness, a roofing underlayment is used, or the slates are sealed using slate sealant.

Roof coverings of natural slate and fibre-cement slate usually belong to the category of light-weight roofs (see Section 5.1.3, Roof Pitch and Areal Weight).

Fire-Rating Slate Roofs

In terms of fire performance, slates of both natural slate and fibre-cement are pre-approved as class BROOF(t2) as they do not contribute to fire (The EU Commission, 2000) (see Section 2.5.1, Fire from the Outside).

5.4.1 Natural Slate

Natural slate tiles are cut from a finely-stratified, layered metamorphic rock type formed by high pressures on mud deposits in static waters. The dominant elements are flaky, clay-like metamorphic rock and fragments of various minerals such as quartz, feldspar, and mica. Furthermore, varying amounts of organic material, such as lime and silicon particles, and sometime volcanic ash may be present. The composition of the slate is vital to its properties.

An important characteristic of natural slate is its cleavability, which results from the layered composition. The slate can therefore be cleaved into uniform thin layers, making it suitable for use as roof covering material. Although slate is cleaved into a somewhat uniform thickness, there will be a certain variation in the thickness of individual slate tiles. Natural slate is sorted into three thicknesses prior to installation. The thickest slates are used at the lower part of the roof and the thinnest are used at the top. Slates from different pallets should be mixed to avoid major colour differences in the roof surface.

Natural slate normally has a long lifespan. However, like other properties, it depends on the compositional mix of the slate, including its mineral content.

Natural slate comes in several colours, depending on where the slate was quarried. Natural slate can be cut into a variety of forms.

Applicable Standards for Natural Slate

Natural slate is subject to the following standards:

- DS/EN 1469, Natural stone products – Slabs for cladding – Requirements (Danish Standards, 2015b)

- DS/EN 12326-1, Slate and stone for discontinuous roofing and external cladding – Part 1: Specifications for slate and carbonate slate (Danish Standards, 2014b)

- DS/EN 12326-2, Slate and stone for discontinuous roofing and external cladding – Part 2: Methods of test for slate and carbonate slate (Danish Standards, 2011d).

Natural slate is subject to the following general requirements:

- Tiles must be free of cleavage planes and materials which may cause breakage in the surface structure.

- The surfaces must be finely stratified, smooth, and even without excessive flaking.

- Edges must be straight and corners right-angled.

- Individual slate tiles must be planed and of even thickness. A deviation of max. 1% of the length of the slate (hollow side down) is permissible.

- When striking the slate, the sound must be a clear tone, like that produced when striking porcelain.

Within Denmark, slate must meet the following requirements:

- Water absorption should average max. 0.4%.

- Tensile bending strength should average at least 70 MPa in dry conditions and 40 MPa in wet conditions. The minimum thickness of the slate to be used can be calculated on the basis of the required strength.

- Calcium carbonate content should average max. 3%. If the slate contains pyrite, which is subject to oxidisation, the calcium carbonate content must be max. 0.5% (and it must be evenly distributed).

- Slate tiles must be frost-proof.

5.4.2 Fibre-Cement Slates

Fibre-cement slates are made of cement mortar reinforced by a mix of inorganic and organic fibres. This production method means that it is possible to produce slates with an even thickness of normally approx. 4 mm.

Fibre-cement slates are produced in various dimensions, for example, 600 × 300 mm, 400 × 400 mm, or 600 × 600 mm. The slates are supplied with or without mitred corners.

Applicable Standards for Fibre-Cement Slates

Fibre-cement slates are subject to the standard: DS/EN 492, Fibre-cement slates and fittings – Product specification and test methods (Danish Standards, 2012d).

5.4.3 Constructing a Slate Roof

Minimum roof pitch requirements for slate roofs depend on the type of slate, for example, natural slate or fibre-cement slate.

Natural slates can normally be used on pitches down to 20 ° as roofing underlayment is almost always used.

Fibre-cement slates can normally be used down to 18 ° roof pitches as roofing underlayment is generally used. For fibre-cement slates measuring 600 × 300 mm, slate sealant may be used to weatherproof slates instead of roofing underlayment on pitches steeper than 34 °.

For further information, please see manufacturer installation manuals and literature. Table 17 provides an overview of different types of slate roof and requirements for minimum roof pitches.

The installations of natural slate roofs and fibre-cement slate roofs are largely identical, but the methods have slight differences.

A slate roof covering is usually installed on a supporting structure of wooden rafters (e.g., attic trusses or lattice trusses) possibly with underlayment, spacer bars, and battens. It is also possible to install a natural slate roof on firm decking (see Figure 89).

Besides the actual slate, the following elements are used in a slate roof covering:

- Underlayment (if required)

- Spacer bars (if roofing underlayment is used)

- Roof battens, and possibly a firm decking made of wood boards

- Slate nails for affixing slate tiles, and slate rivets for fibre-cement slates

- Slate sealant for weatherproofing if no underlayment is installed

The roof must be vented according to applicable guidelines (cf. Section 2.3.3, Guidelines for Ventilation of Pitched Roofs). Venting is usually installed at the eaves and openings are fitted with insect mesh or bird grating. They are also installed at the ridge level, using either vent cowls or ridge solutions with integral ventilation.

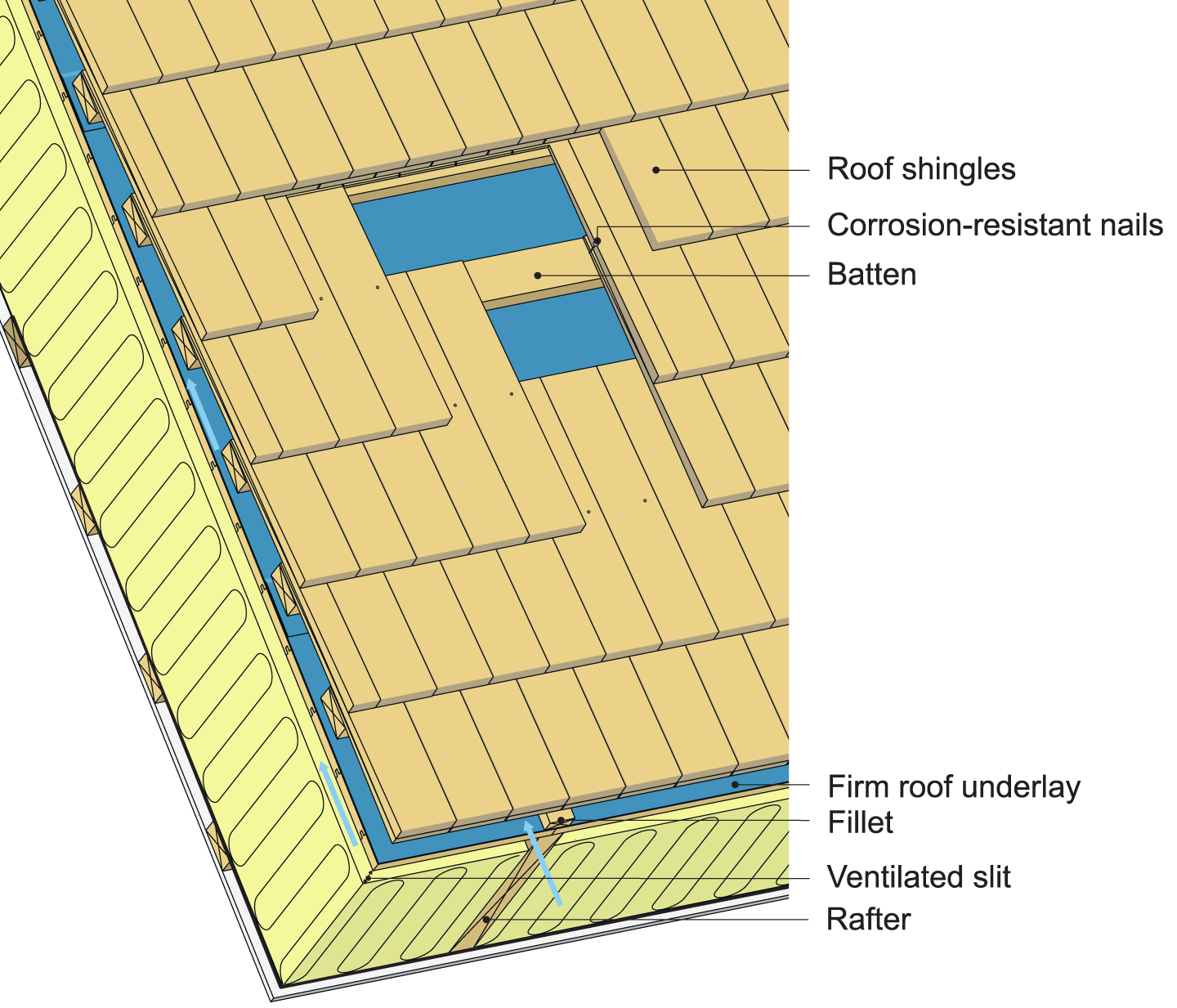

Examples of roof assemblies with fibre-cement slate and natural slate roof coverings are shown in Figures 86, 88, and 89.

Figure 86. An example of a roof assembly with fibre-cement slates and a vented firm underlayment. The slates are fixed using nails and so-called disc rivets placed between the slates, so that the top part of the rivet fixes two slates (see Figure 87).

Figure 87. An visualization of disc rivets, used for affixing fibre-cement slates.

Figure 88. An example of a roof assembly using natural slates and vented roll-material underlayment.

Figure 89. An example of the laying of natural slates directly on a firm underlayment supported by wood-board decking. The underlayment must be installed using ’self-healing’ materials (e.g., bituminous felt which will fit snugly around nail holes).

Roofing Underlayment

Slate roof coverings are usually laid with an underlayment, but supplementary weatherproofing for fibre-cement slates installed on roofs with a pitch above 34 ° can also be achieved using slate sealant.

Roofing underlayment issues and concerns, including the venting of underlayment, are outlined in Section 3, Roofing Underlayment.

Spacer Bars

Spacer bars are used in roofs with underlayment to:

- Raise the roof battens to enable water and dirt to pass under the battens

- Ensure that the roofing underlayment is fixed securely

- Ensure adequate ventilation on the underside of the roof covering in conjunction with eaves air-intake and ridge exhaust.

Issues concerning spacer bars are detailed in Section 3.1.2, Spacer Bars.

Battens or Purlins

Slates are laid over and affixed to roof battens. For the sake of the strength and rigidity of the structure, strength-graded roof battens or purlins labelled strength grade C18 must be used (cf. DS/EN 14081-1) (Danish Standards, 2016c). Rules and guidelines for roof battens are listed in Section 2.6.1, Roof Battens. For rafter spacing exceeding 1000 mm measured from centre-to-centre (c.t.c.), dimensions of C18-labelled battens are specified in a batten table in TRÆ 65, Taglægter (Roof Battens) (Træinformation, 2011b).

When installing roof battens, a tolerance of ± 3 mm measured across the rafters must be allowed (cf. www.tolerancer.dk and Træ 65, Taglægter (Roof Battens)) (Træinformation, 2011b). Tolerances must not be allowed to accumulate in the structure.

Issues concerning roof battens are also outlined in Section 2.6.1, Roof Battens.

Manufacturer information sheets will list the support spacing required for their products. The spacing depends on the type of slate and specific slate form.

5.4.4 Laying a Slate Roof

Before laying the tiles, the following special focus areas should be checked:

- The net coverage. This should be determined with a trial installation, including checking whether the net coverage is consistent with the total width of the roof surface. It may be necessary to adjust the assembly by adapting the width of the overhang or by changing the position of the slates on the roof.

- The squareness of roof surfaces. This can be checked by measuring the diagonals on the roof surface against the length of the roof surface at eaves and ridges.

- The bearing length should correspond to the length specified by the manufacturer.

- Rafters and roof battens should be straight. Checks made using a 2-metre smoothing board should indicate that any deviations are max. 15 mm and are evenly distributed.

- The roof underlayment should lie correctly, should be tightly installed, and should be undamaged.

- The roof underlayment can be brought over the barge board, if applicable.

- That spacer bars should be at least 25 mm thick and made of pressure-impregnated timber, and should be installed between roofing underlayment and battens.

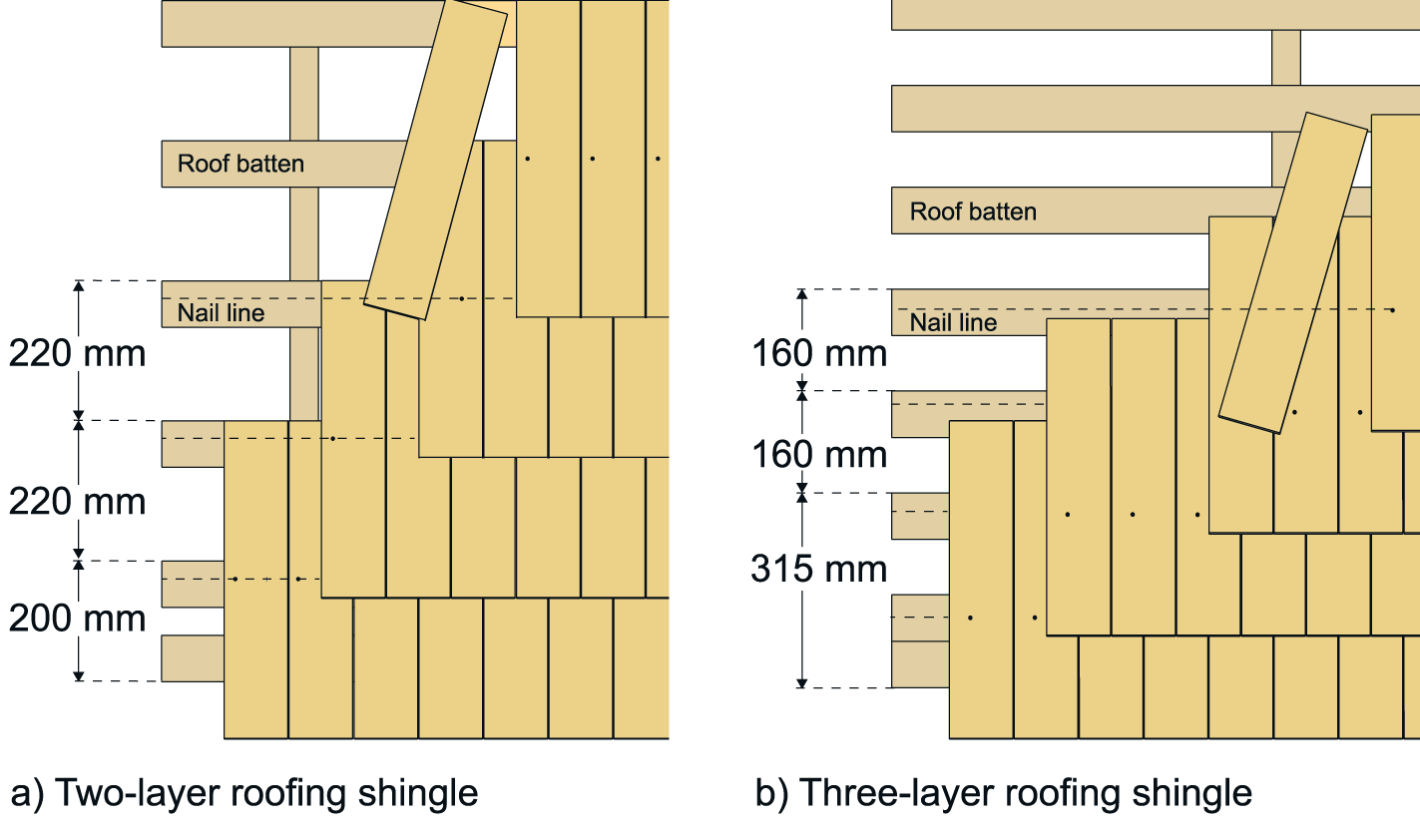

Laying the Slates

Slates are normally laid on battens installed at the manufacturer specified spacing or the spacing determined by a trial installation. Furthermore, natural slates can be fixed directly on tongue-and-groove board decking covered with bituminous felt, or a similar ’self-healing’ material that will close snugly around nail holes made when fixing the slates. The boards are installed with a spacing of 1–2 mm. This roof structure is common among old properties in Copenhagen and is often used in other countries such as Sweden. To avoid flexion when nailing, the boards must be at least 25 mm thick but ideally 34 mm thick.

Where possible, the length and width of the roof surface should be adapted to the chosen slate type in the design phase, to avoid having to cut the slate. If cutting is unavoidable, all slates (typically at gable ends and penetration) should be cut to a size that is bigger than half of the slate’s width.

Slates are installed at right angles to the eaves, normally with a spacing of 1–5 mm. It is a good idea to mark up a construction line at right angles to the eaves. A line should typically be marked for every third slate.

The first row of battens and the (invisible) first slates are installed so that they project 30–40 mm into the gutter (measured horizontally) (which is consistent with the slates typically projecting 60–70 mm from the underside of the lowermost batten). The first batten must be blocked up by a thickness consistent with a slate, so that the bottom row of slates will have the same pitch as the rest. Care should be taken to establish the required air gap between the batten’s lower edge and the cleat edge flashing, if installed. This should also be established at the ridge.

Starting with the bottom batten, the position of the rest of the battens should be marked with the applicable spacing, observing the measurements specified by the manufacturer.

The slates should then be installed beginning from the reference line towards the gable ends. This will ensure that the outermost slates at both gable ends will have identical widths if the roof surface area is not divisible by a whole number of slates.

Eave slates are adapted to fit the chosen installation method. Similarly, it will be necessary to adapt slates at penetrations and ridges.

When installing fibre-cement slates diagonally, the first slates are adapted in a similar way. The slates are laid so that their top points align with the upper edge of the batten with a slight spacing between the slates, allowing disc rivets to be fitted. The slates are staggered by half a width between rows.

Fixing the Slates

Slate nails and disc rivets are used to fix slates to the roof battens. Nails must be weatherproof and non-corrosive (e.g., hot-galvanised or copper nails).

Fibre-cement slates are usually supplied with pre-punched holes to facilitate installation. In natural slates, fixing holes are typically pre-punched from the backside of the tiles. This results in cone-shaped holes for countersinking the slate nails.

The bottom edge of the fibre-cement slates is fixed using disc rivets fitted between the two slates below with its point directed upwards (see Figure 86). When installing, the point of the disc rivet should be inserted through the pre-punched hole. The point will bend down.

For connections and penetrations (e.g., roof lights) slates are fixed using rust-resistant screws with EPDM washers.

5.4.4 Details – Slates

This section describes examples of typical detail design for roofs with slate coverings. See manufacturer installation instructions and further details.

In the design of roof details, it is necessary to take general guidelines for several issues into account (e.g., guidelines concerning ventilation and Building Regulations provisions relative to fire safety and thermal insulation). General issues concerning the choice of roof are outlined in Section 1.1, Roof Design.

For further examples of roof detail design, please see Section 6, Dormers, Roof Lights, and Skylights, Section 7, Flashings – Penetrations and Intersections, and Section 9, List of Examples.

Ridge Solutions

Figure 90. . An example of a slate roof with a firm underlayment and a vented ridge. Ventilation is achieved via roof vents in the underlayment and via ridge elements with integral vent openings.

Figure 91. An example of ridge ventilation design in a slate roof under blocked-up ridge boards with zinc flashing. The blocking is achieved using spacer bars spaced at least 600 mm from each other (and max. 250 mm long).

Eaves

Figure 92. Examples of eaves for slate roofs with a firm underlayment. For solution a), the insect mesh can also be placed above the soffit boards. For solution b), there must be spacing of at least 20 mm between the gutter and the wall, ensuring the free flow of ventilation air.

5.5 Metal Sheets

In this book, metal sheets are used to denote a roof covering constructed using plane and thin prefabricated metal sheets or roof tiles with different profiles. Roof coverings using roll-formed zinc, copper, or aluminium sheets are outlined in Section 5.6, Zinc and Copper (and Aluminium).

Prefabricated, profiled metal sheet roof coverings are often systems solutions with various types of special sheets for different roof details (e.g., eaves, overhang, ridges, and gable ends). Similarly, the method of fixing and joining the sheets is often specific to the sheet system used. Manufacturers’ installation manuals must always be followed to ensure a satisfactory result.

The max. span of profiled sheets is relative to the specific profiling. For long sheets, it is sometimes possible to use a batten spacing of up to 2 metres approximately.

The weathertightness of metal sheet roofing is achieved with overlaps or lap joints between individual metal sheets held in place by screws or clicked into place (with click seams). To ensure watertightness or to collect condensate on the underside, metal roofs should be constructed using roofing underlayment.

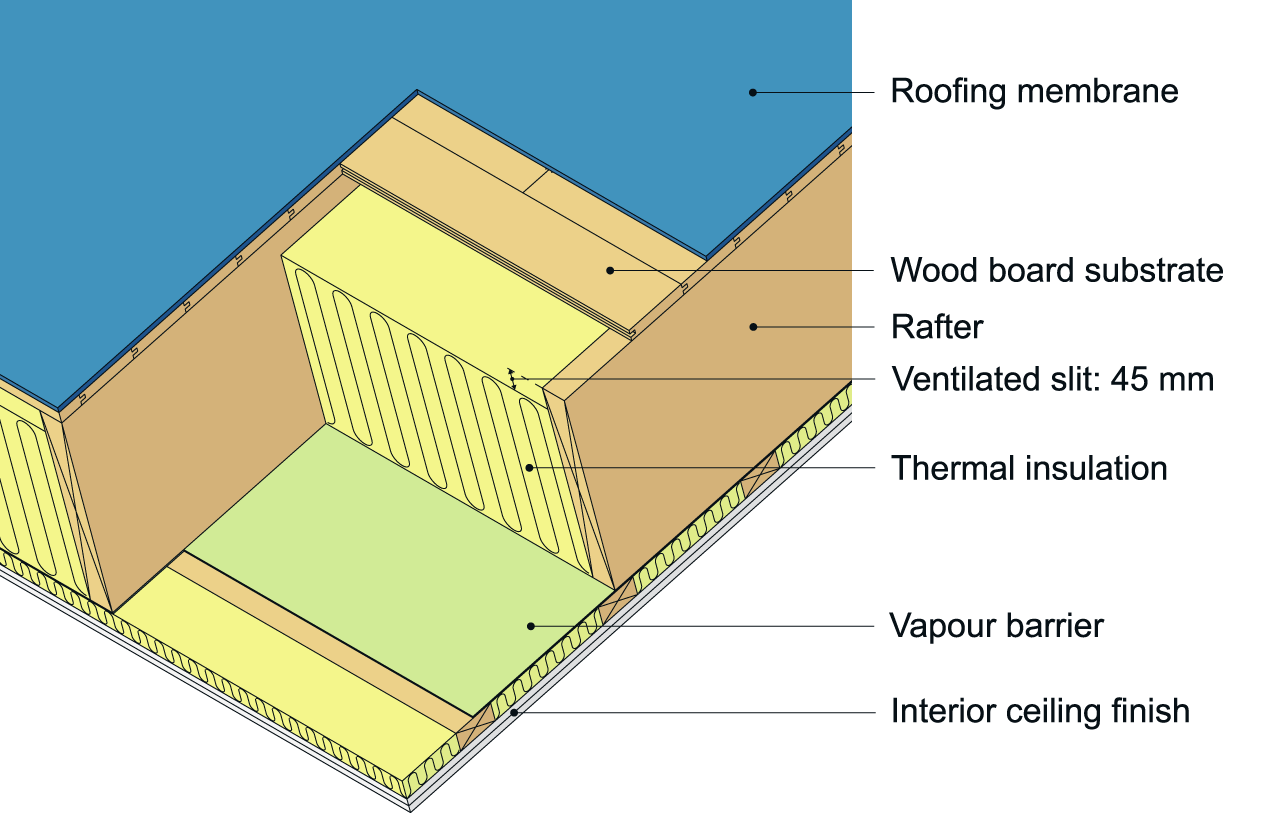

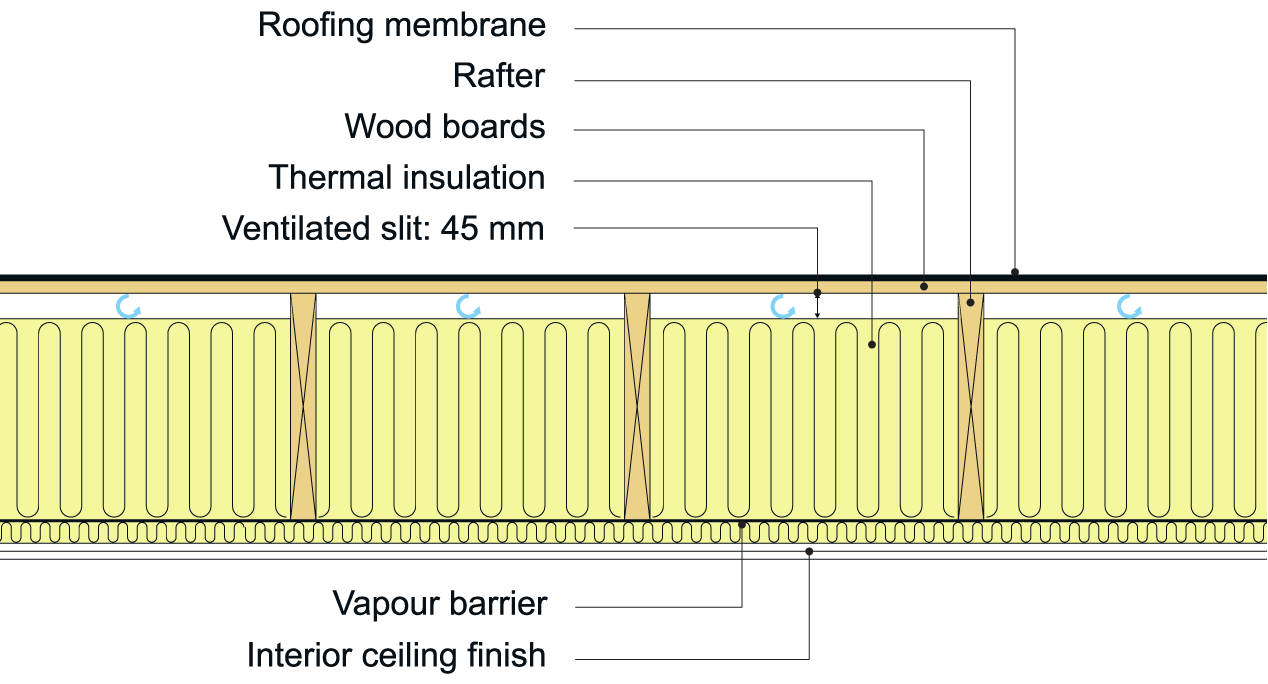

Metal roof sheets are vapour-impermeable and are normally used in vented roof assemblies only (see Section 1.2, Vented and Unvented Assemblies).

Roofs with a metal sheet covering belong to the category of light-weight roofs (see Section 5.1.3, Roof Pitch and Areal Weight).

The lifespan of metal sheets is relative to the metal used as well as to surface treatment or coating.

Fire-Rating Metal Sheet Roofing

Metal roofing with a thickness of at least 0.4 mm laid on battens are pre-approved as BROOF(t2) as they do not contribute to fire (The EU Commission, 2000) (see Section 2.5.1, Fire from the Outside). For other applications such as installing a roof covering on a thermal insulation underlay, the manufacturer is obliged to advise on the types of underlay suitable for the specific roof covering to protect underlying materials in the roof assembly.

Applicable Standards for Metal Roofing Sheets

Metal sheets used as roof covering are subject to DS/EN 508, Roofing and cladding products from metal sheet – Specification for self-supporting of steel, aluminium, or stainless steel sheet – Part 1: Steel (Danish Standards, 2014c).

5.5.1 Types of Metal Sheet

Metal roofing sheets are available in several different types/designs, for example:

- Trapezoidal or sinusoidal long sheets

- Roof-tile shaped long sheets

- Click-seam sheets with a prefabricated seam

Roofing sheets are made of galvanised steel, aluminium, or, in rare cases, stainless steel. Sheet thickness is usually between 0.4 and 1 mm. Sheets thinner than 0.5 mm are not recommended.

The profile type and dimension of the metal sheets are significant determinants for the roof assembly (e.g., for batten spacing) (see Section 5.5.2, Constructing a Metal Sheet Roof).

Figure 93 shows examples of different designs of prefabricated metal sheets for roof covering.

Figure 93. Examples of prefabricated metal sheets designed for roof covering.

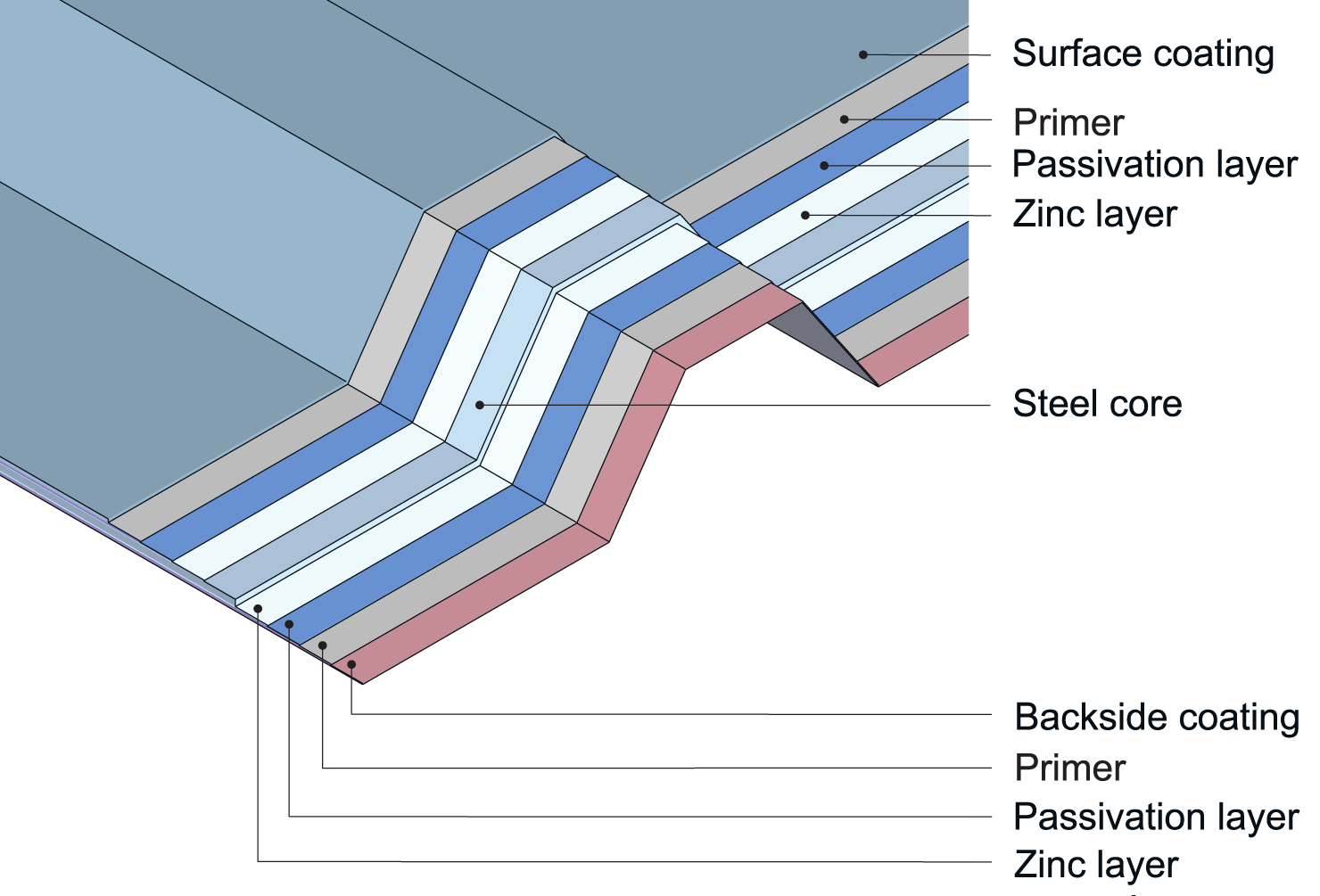

Surface Treatment

The surface treatment of metal sheets for roof covering is assessed in relation to corrosion protection, scratch resistance, UV-resistance, and easy cleaning.

Steel sheets for roof covering are always zinc-coated (galvanised), and any surface coating is thus applied to the zinc (see Figure 94). Galvanised sheets are available where aluminium has been added to the zinc layer to improve the corrosion protection (aluzinc). Stainless steel sheets are also available which can be used untreated.

The quality of the surface treatment is a major determinant of the longevity of the sheets.

Materials used for surface treatment are typically polyester or other weathertight materials (e.g., PVF2, PVC, or PUR).

Aluminium sheets can be surface-treated like steel sheets, but can also be used without surface treatment as a thin layer of aluminium oxide (Al2O3) forms naturally over Aluminium when it is exposed to air, and this layer will durably protect the surface. The use of untreated aluminium sheets requires that they be a quality suitable for free exposure and that no galvanic corrosion will occur (e.g., due to fixings made of unsuitable materials).

Aluminium sheets can also be surface treated through anodising.

Figure 94. Typical coating structure in metal roofing sheets

5.5.2 Constructing a Metal Sheet Roof

Roofing executed using prefabricated metal sheets is suitable for relatively shallow pitches. However, mechanical joints in metal sheet roofing (e.g., executed as lap joints) are not resistant to water pressure and the minimum roof pitch for these is therefore somewhat higher than for roofing membranes. The roof pitch for profiled (corrugated) metal sheets is often 10–15 °. For shallower pitches (down to approx. 5 °) it will be necessary to use sealants in the joints or roofing underlayment.

Some manufacturers (e.g., of aluminium sheets which are seamed on site, and click-seam sheets with prefabricated seams) permit the use of their products on shallow roof pitches down to 3 °. Pitches as shallow as this require a special assembly protocol and it is essential to follow the manufacturer’s instructions carefully.

For shallow roof pitches, a structured mat is fitted under the aluminium sheets if they are installed on sheet material or rigid-foam thermal insulation.

Interstitial condensate will often form on the underside of metal sheet roofing due to the rapid cooling caused by radiation emission to the atmosphere at night. For this reason, metal sheet roofing should normally be executed using roofing underlayment capable of intercepting dripping condensate. Furthermore, the underlayment provides added security against the ingress of water, via sheet joints for example. Roof underlayment should not be omitted when renovating old houses where there is uncertainty about the degree of airtightness or vapour barrier airtightness.

If the roofing underlayment is omitted, sheets with a condensate-absorbing underside (condensate absorber) must be installed. However, their absorbency is limited and cannot sustain heavy moisture loads. Condensate absorbers on the underside are available in the form of felt or absorbent paint. Felt will absorb up to approx. 1 kg of condensate per m2 while absorbent paint will absorb up to approx. 0.5 kg/m2, which makes it feasible to use sheets without roofing underlayment in moisture load classes 1 and 2 (i.e., above relatively dry rooms) (see Section 1.2, Vented and Unvented Assemblies).

Metal sheet roofing may cause noise problems from rain and hailstones, which must be subject to evaluation in specific contexts. Some profiled sheets are available with sound reduction on the underside and will thus reduce noise nuisance.

Due to the relatively large changes in temperature in metals, steps must be taken to allow for thermal deformation (expansion, and contraction) in the installation phase.

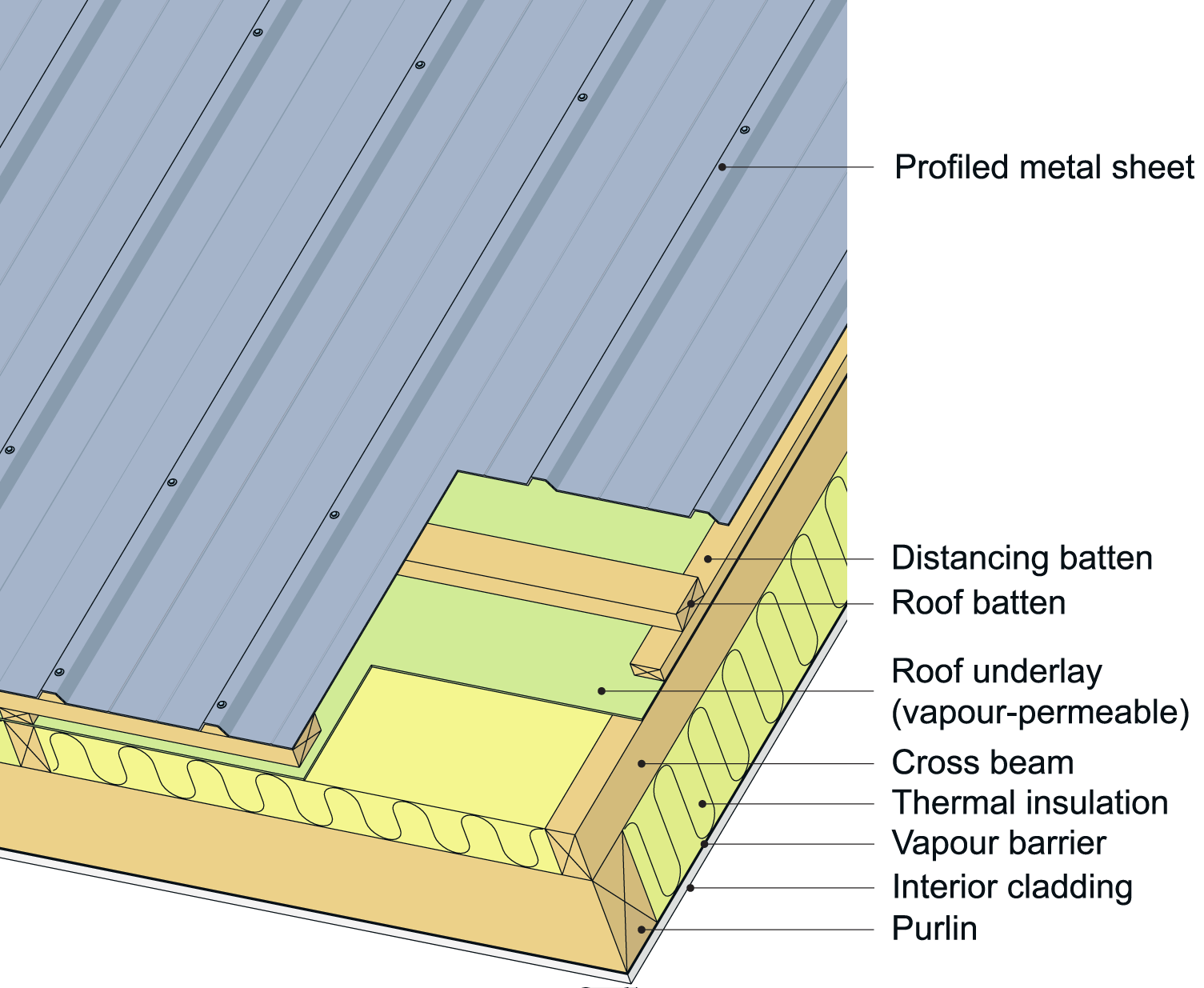

A roof covering of prefabricated profiled metal sheets is installed on a supporting structure of timber rafters or purlins.

In addition to the actual metal sheets, the following elements are used in a metal sheet roof covering:

- Underlayment (if required)

- Spacer bars (if roofing underlayment is used)

- Battens or purlins

- Screws for fixing the sheets, and possibly a sealant

- Walk-proof underlay (if required)

Metal sheet roofing must be vented in accordance with applicable guidelines (cf. Section 2.3, Roof ventilation). Normally, venting is achieved at the eaves with openings fitted with insect mesh or bird grating, and at the ridge using either vent cowls or ridge solutions with integral ventilation.

Guidelines on the use of roofing underlayment are outlined in Section 3, Roofing Underlayment.

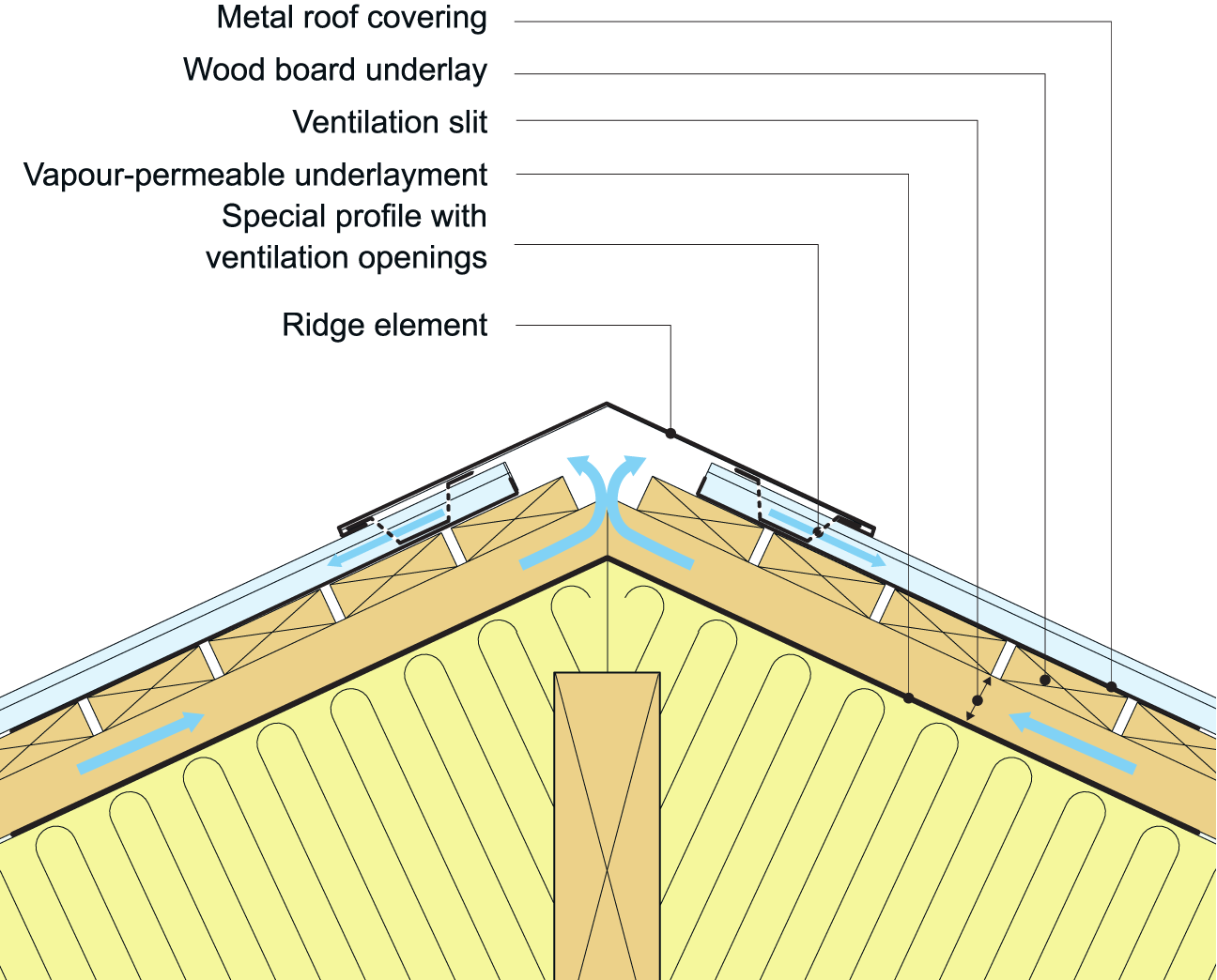

A wood board underlay could consist of 23 × 100 mm rough (equalised) timbers installed with 5–10 mm spacing.

If seamed aluminium sheets are installed on plywood sheet decking, roofing underlayment must be installed if the shallow roof pitch is below 10 °. For aluminium sheets, structured matting is usually unnecessary, although some manufacturers recommend it for shallow roof pitches.

Figures 95–97 show examples of roof assemblies with roof coverings of long, profiled sheets.

Figure 95. An example roof assembly with profiled metal sheets and vapour-permeable roofing underlayment. The sheets are installed on battens.

Figure 96. An example roof assembly with metal sheets on battens with vapour-permeable roofing underlayment on a supporting structure of purlins (e.g., resting on an underlying steel frame construction (not shown)).

Figure 97. An example of a roof assembly with profiled metal sheets on lattice trusses with battens and roofing underlayment.

Roof-Tile Profiled Sheets

Two types of roof-tile profiled sheets are available: one with a length corresponding to the batten spacing (see Figure 98), and one with continuous roof-tile profiles spanning several battens.

Figure 98. An example roof assembly with vapour-permeable roofing underlayment and roof-tile profiled metal sheets spanning two roof battens.

Seamed Sheets on a Firm Underlay

Click-seam sheets and sheets seamed on site must be laid on a firm wood-board or plywood decking. With roofing underlayment, these two types can be used for shallow roof pitches down to 3 °.

Figure 99. An example roof assembly with click-seam metal sheets on plywood roofing underlayment. For shallow pitches, structured matting between metal sheets and plywood is used (see Figure 100).

Figure 100. Examples of joining roofing sheets with a click-seam (see Figure 99).

- Click-seam joint on wood board decking.

- Click-seam joint on plywood decking with structured matting.

Figure 101. An example roof assembly with seamed metal sheets on wood board decking. If Plywood is used as decking it may be necessary (dependent on the roofing materials used and the roof pitch) to use structured matting underneath the metal sheet, particularly for shallow pitches.

5.5.3 Installing Metal Sheet Roofing

Since metal sheet roofing is available in many different materials and designs, no general installation or laying guidelines will be given here.

We recommend that metal sheet roofing is always installed on a roofing underlayment both to ensure tightness in overlap joints and to intercept any dripping condensate. Alternatively, dripping condensate can be avoided by using roof covering sheets with a moisture-absorbent underside (see Section 5.5.2, Constructing a Metal Sheet Roof).

Dimensioning and design must be performed in accordance with manufacturer instructions, including maximum span of the sheets, sheet overlap in both horizontal and vertical joints, and fixings. The sheets should be sufficiently robust to tolerate minor mechanical impact without becoming deformed and without damaging the coating.

The sheets must be fixed in such a way as to absorb wind loads on the roof. This requires sufficient anchorage length in the underlying structure (e.g., with battens or purlins).

5.5.4 Details – Metal Sheets

This section shows examples of typical detail design used in prefabricated profiled metal sheet roofing. See manufacturer installation instructions for more detail.

In the design of roof details, it is necessary to adhere to general guidelines for several issues. These include guidelines concerning ventilation and Building Regulations for fire safety and thermal insulation. General issues concerning the choice of roof are outlined in Section 1.1, Roof Design.

For further examples of roof detail design, please see Section 6, Dormers, Roof Lights, and Skylights, Section 7, Flashings – Penetrations and Intersections, and Section 9, List of Examples.

Ridges

Figure 102. An example of a fascia verge design in a profiled metal sheet roof covering.

Fascia

Figure 103. An example fascia verge design using a profiled metal sheet roof covering.

Wall Flashing

Figure 104. An example of wall flashing. Shown here with flashing fixed to the metal roof covering and wall. The flashing is further protected by a counter-flashing mounted in a 30 mm deep groove milled into the wall. The groove is sealed with caulking compound.

Joining Metal Sheets

Figure 105. Examples of end lap joints for profiled metal roof sheets.

- End lap for roof pitch steeper than 15 °.

- Minimum end lap for roof pitch shallower than 15 °.

Figure 106. An example of side lap joints for profiled metal roof sheets. In certain cases, screws are placed in the profile valleys, which lead to a heavier water load in screw sheet penetrations.

5.6 Zink, Copper and Aluminium

Zinc and copper roof coverings are traditionally executed in sheeting supplied as roll-formed sheets or so-called coils (rolls) which are subsequently shaped for use as roof covering material. Similar applications are possible for aluminium sheets. Within this chapter, these types of roof coverings are referred to as zinc or copper, which are the most commonly used products of this type.

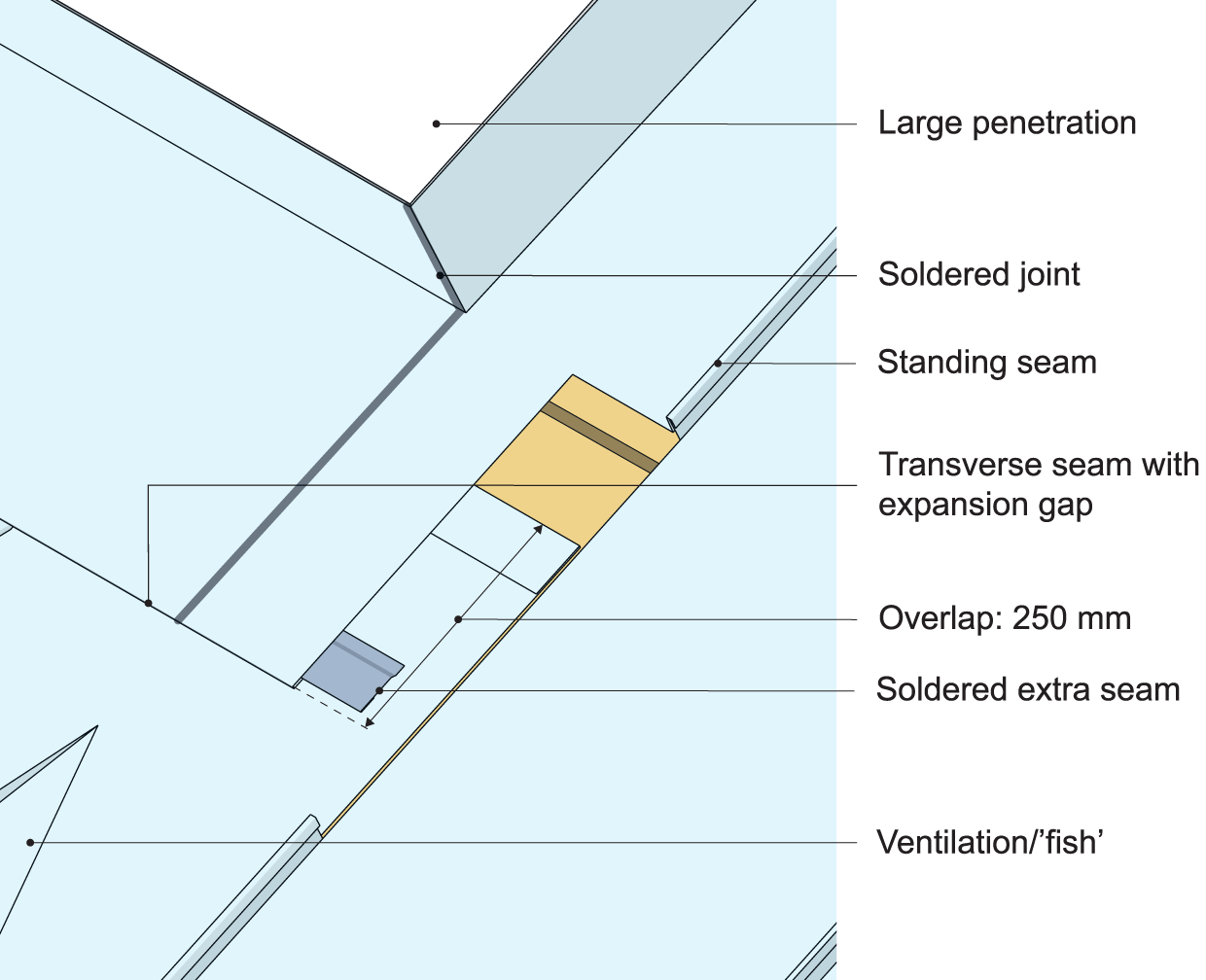

Weathertightness in zinc, copper, and aluminium roof coverings is achieved with seamed joints between the individual lengths or sheets of metal.

Zinc, copper, or aluminium roof coverings belong to the category of light-weight roofs (see Section 5.1.3, Roof Pitch and Areal Weight).

Fire-Rating Zinc, Copper, and Aluminium Roofs

Zinc, copper, and aluminium are usually laid on wood boards or non-flammable thermal insulation. However, this construction is not covered by the BROOF(t2) pre-approval of the EU Commission (The EU Commission, 2000) (see 2.5.1, Fire from the Outside). The roof covering manufacturer is obliged to advise on the types of underlayment suitable for their specific roof covering.

5.6.1 Zink

Zinc has been used as a roof covering for more than 150 years. Zinc is manufactured as an alloy of almost pure zinc to which small quantities of copper and titanium are added. In the production process, the zinc is melted and roll-formed into sheets or coils (see Figure 107).

Zinc lengths for roof covering are normally between 470 and 670 mm wide. This gives an effective width of 400–600 mm between the seams. Widths with a spacing of more than 600 mm between seams should be avoided.

The material thickness is normally between 0.65 mm (zinc 12) and 0.8 mm (zinc 14).

The material is not usually given any anti-corrosion treatment. After the production process, zinc sheets are glossy (natural zinc or cold-rolled zinc). Natural weathering will add a matt grey coating of zinc carbonate to the zinc surface, forming a natural protection.

Zinc is available in several pre-patinated versions ranging from light grey to a dark anthracite grey colour. The pre-patination is achieved with a chemical surface treatment applied during the production process, which alters the colour of the surface.

Zinc is also available in several lacquer-coated versions.

Figure 107. Zinc and copper roof coverings are supplied in sheets or coils.

Applicable Standards for Zinc

Zinc for roof covering purposes is subject to the following European standards:

- DS/EN 988, Zinc and zinc alloys. Specification for rolled flat products for building (Danish Standards, 1996).

- DS/EN 506, Roofing products of metal sheet – Specification for self-supporting products of copper or zinc sheet (Danish Standards, 2008).

Specific qualities of zinc:

- Density: 7200 kg/m3

- Melting point: 418 °C

- Expansion coefficient: 0.022 mm/(m °C)

- Can be soft-soldered

5.6.2 Copper

Copper for roof covering purposes is made from almost (99.9%) pure copper. During manufacture, the copper is cast and roll-formed into sheets or coils (rolls). These are normally 1 metre wide and 0.6 or 0.7 mm thick.

The copper is oxidised, giving it a green surface of alkaline copper carbonate. In areas with a high concentrations of sulphur in the air, copper tends to turn black.

Applicable Standards for Copper

Copper for roof covering purposes is subject to the standard DS/EN 1172, Copper and copper alloys – Sheet and strip for building purposes (Danish Standards, 2012f).

Specific qualities of copper:

- Density: 8900 kg/ m3

- Melting point: 1083 °C

- Expansion coefficient: 0,017 mm/(m °C).

- Can be soft-soldered, hard-soldered, and welded

5.6.3 Constructing Zinc and Copper Roofs

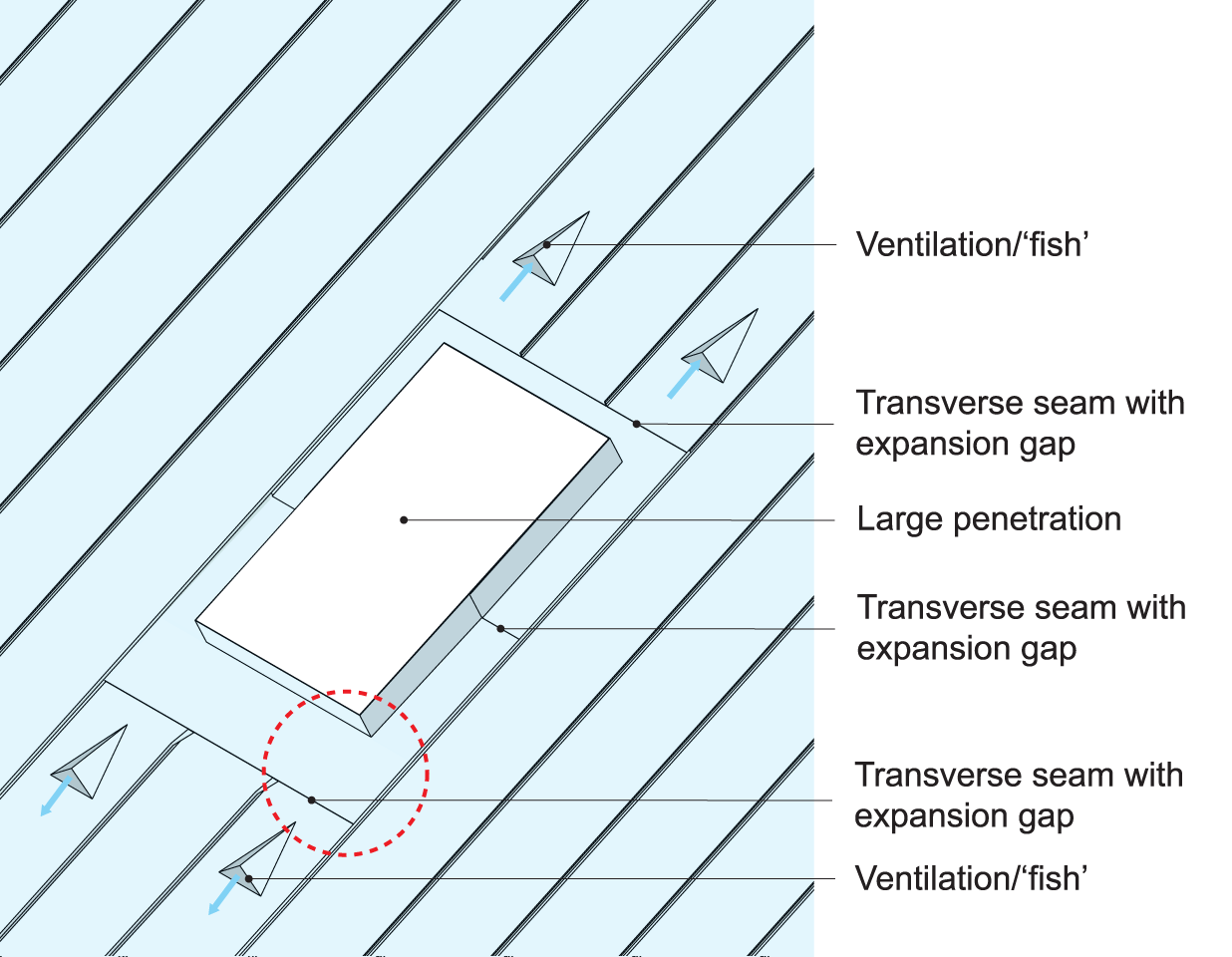

The roof pitch for seamed zinc or copper roofs is min. 5 °. However, roof pitches below 15 ° or roofs in exposed locations require certain precautionary measures to prevent water ingress (e.g., sealant applied in seamed joints and carefully executed and positioned flashings). Some zinc manufacturers allow the use of zinc down to a 3 ° pitch. This requires careful observation of manufacturer instructions. For shallow pitches special attention must be given to waterproofing details, particularly valleys.

A zinc or copper roof covering is normally installed on a supporting structure of wooden rafters such as attic trusses or lattice trusses.

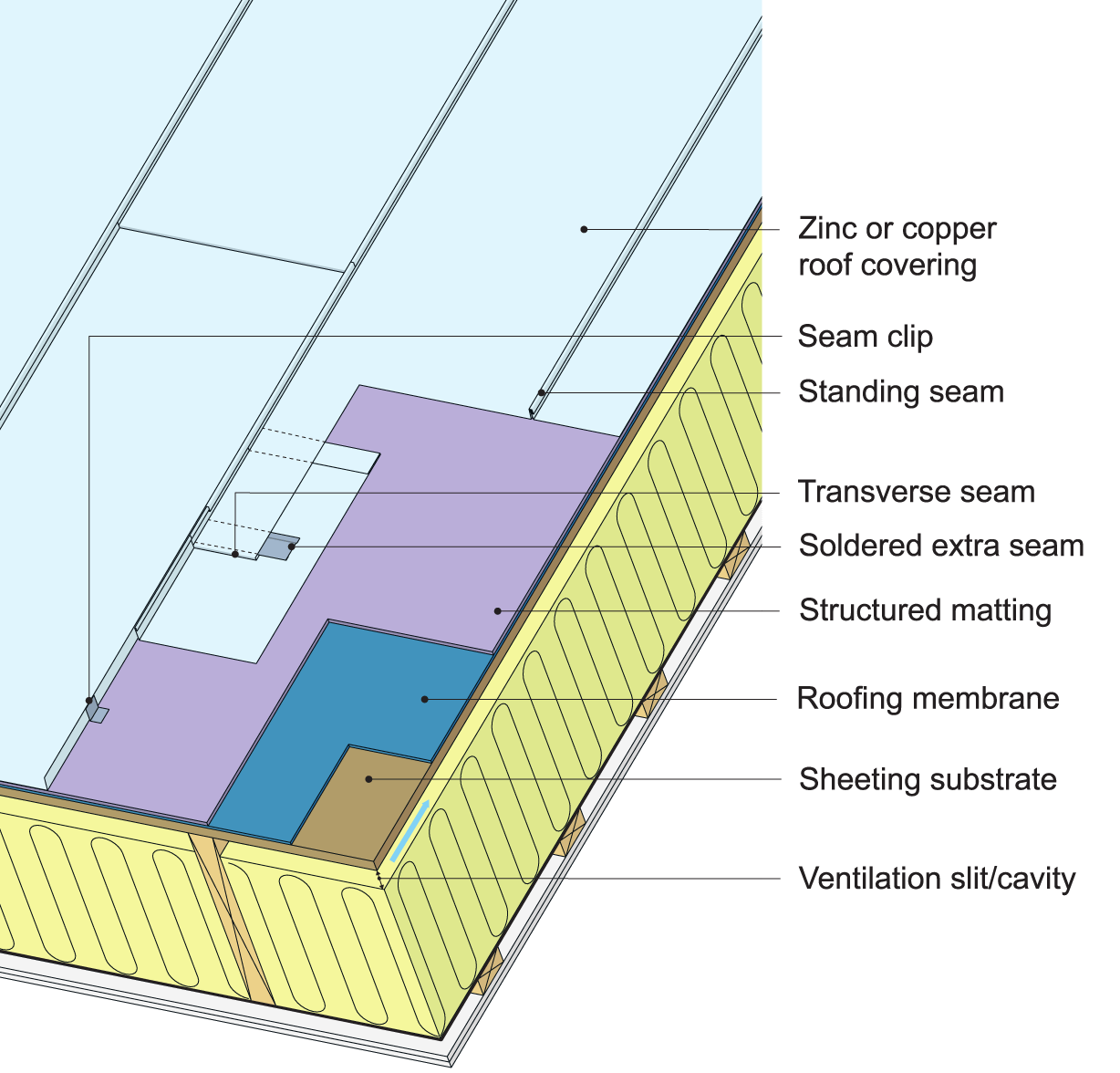

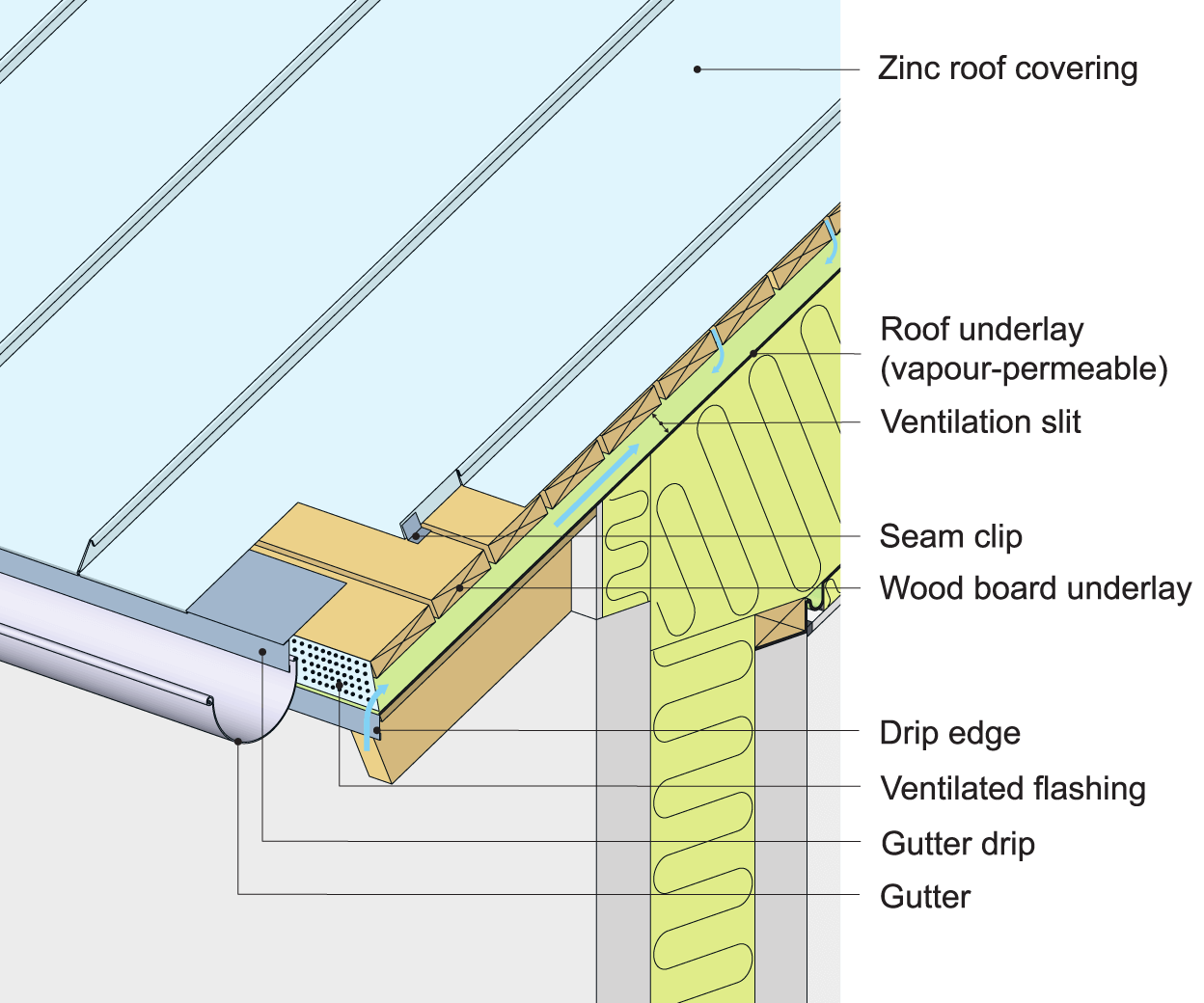

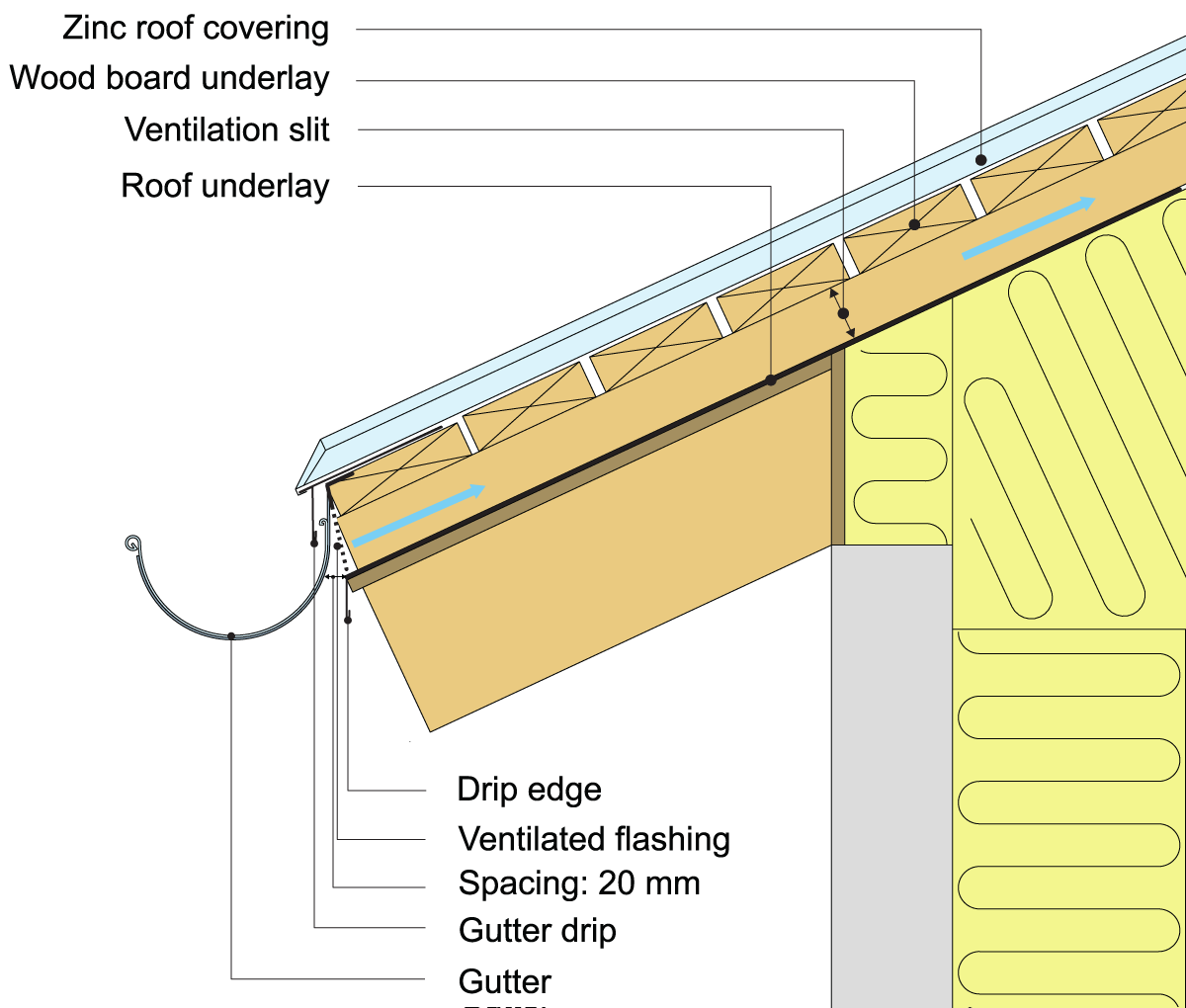

Apart from the actual zinc and copper covering, the following elements are used in the roof assembly:

- Underlayment (if required)

- Spacer bars (if roofing underlayment is used)

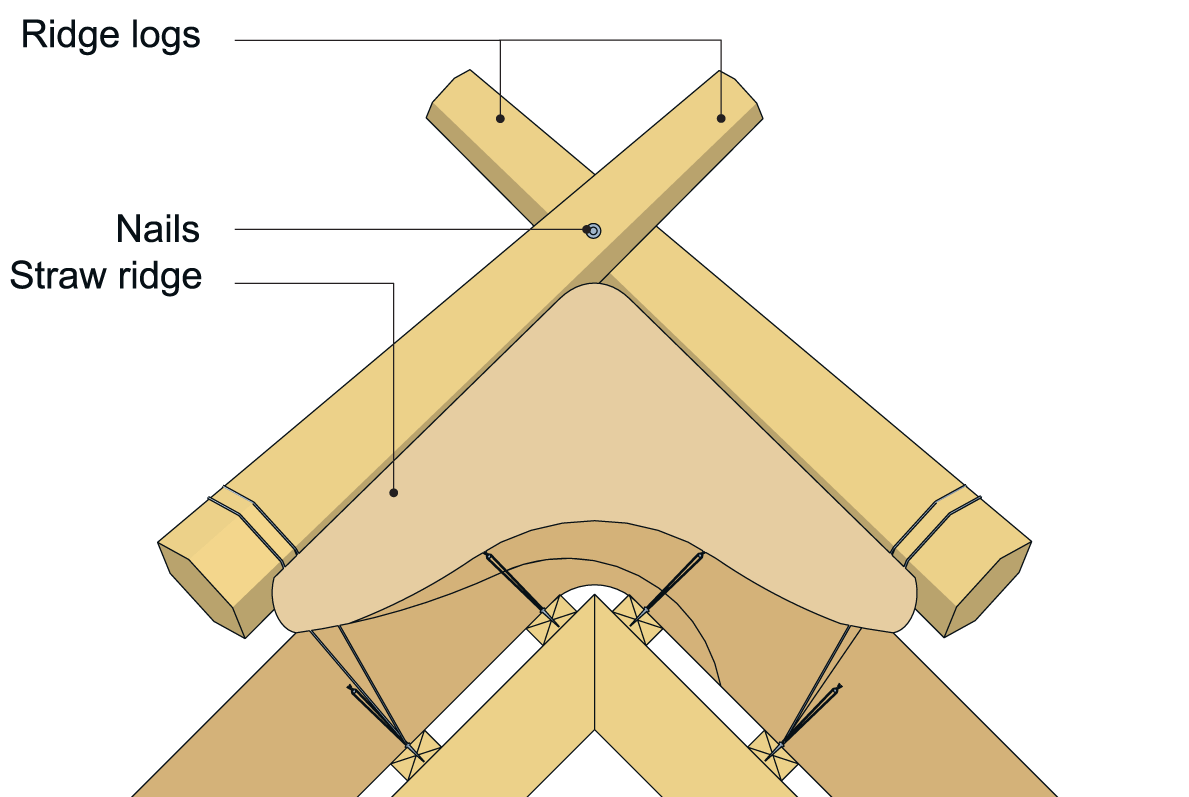

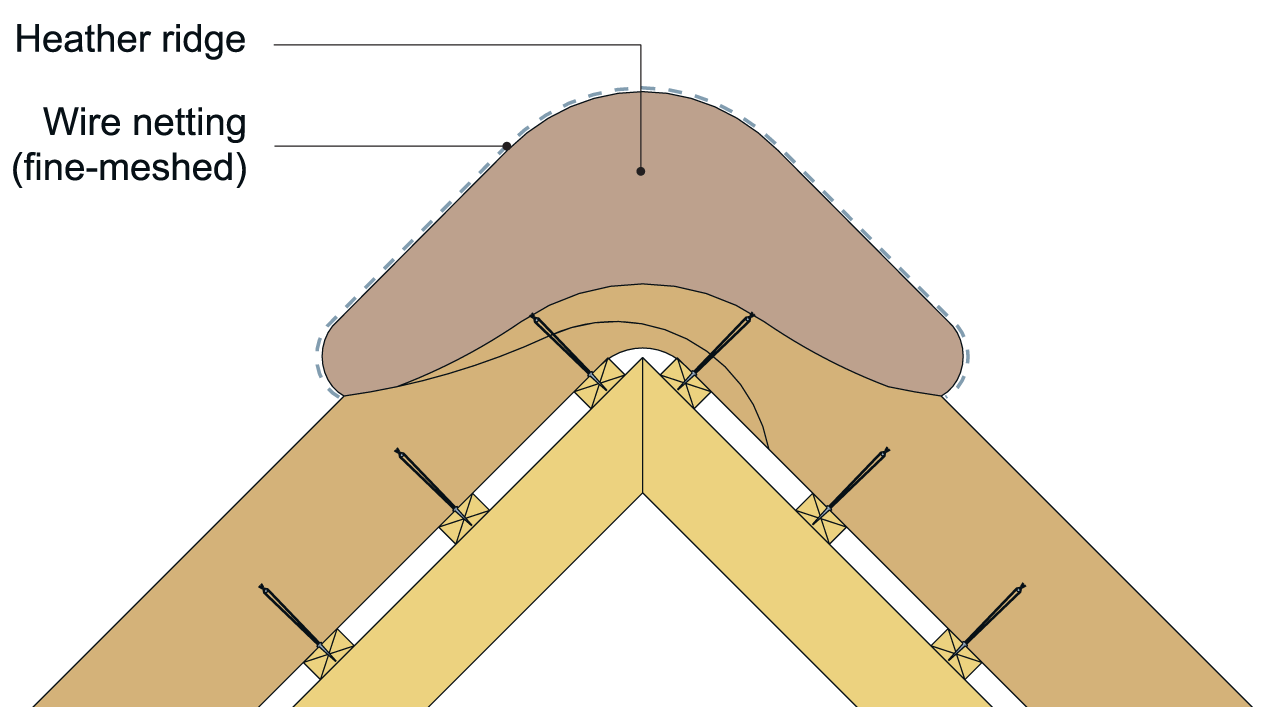

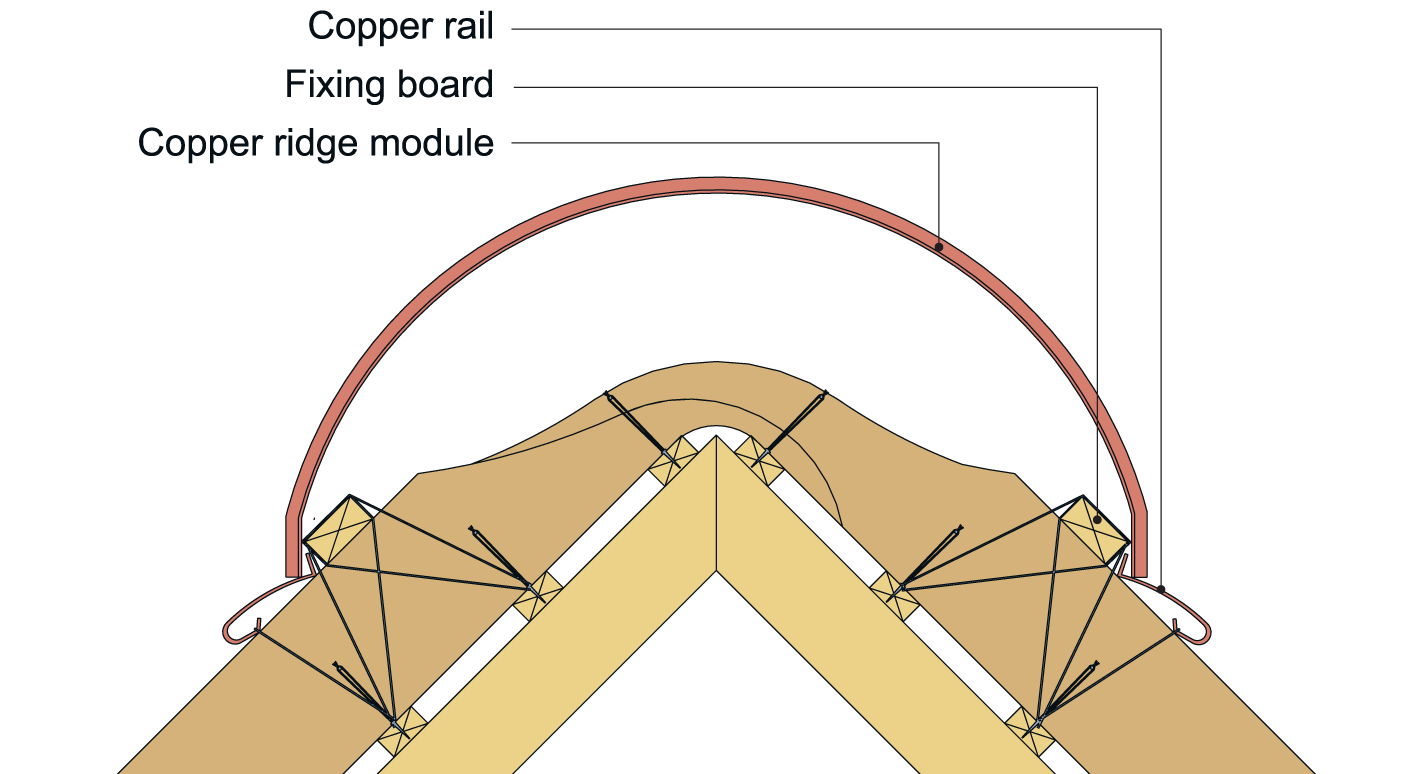

- Underlay of wood boards, sheeting, or thermal insulation

- Structured matting (if wood board or thermal insulation underlayment is used)

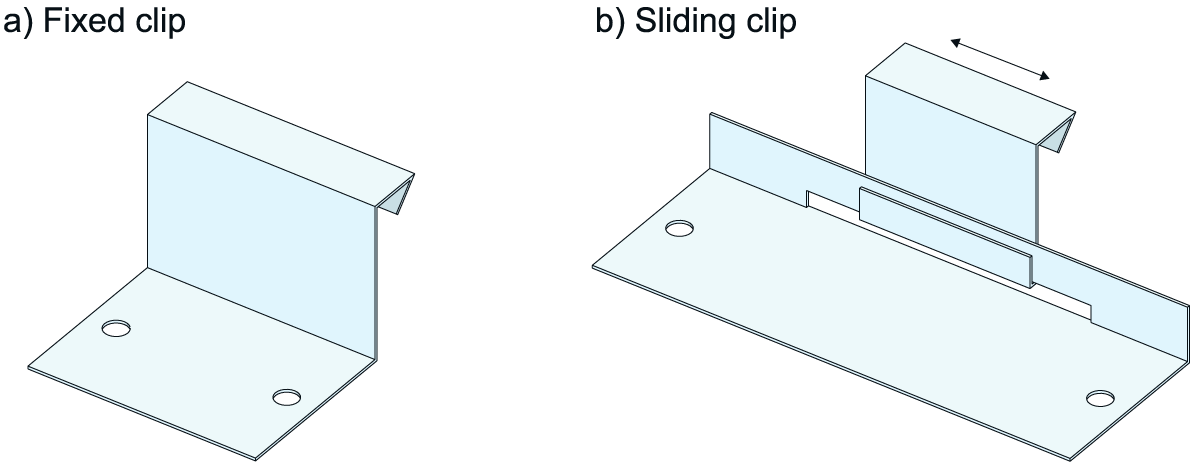

- Seam clips and nails for fixing and a seam sealant (if required)

Furthermore, exposed locations will require the application of seam sealant to avoid water ingress.

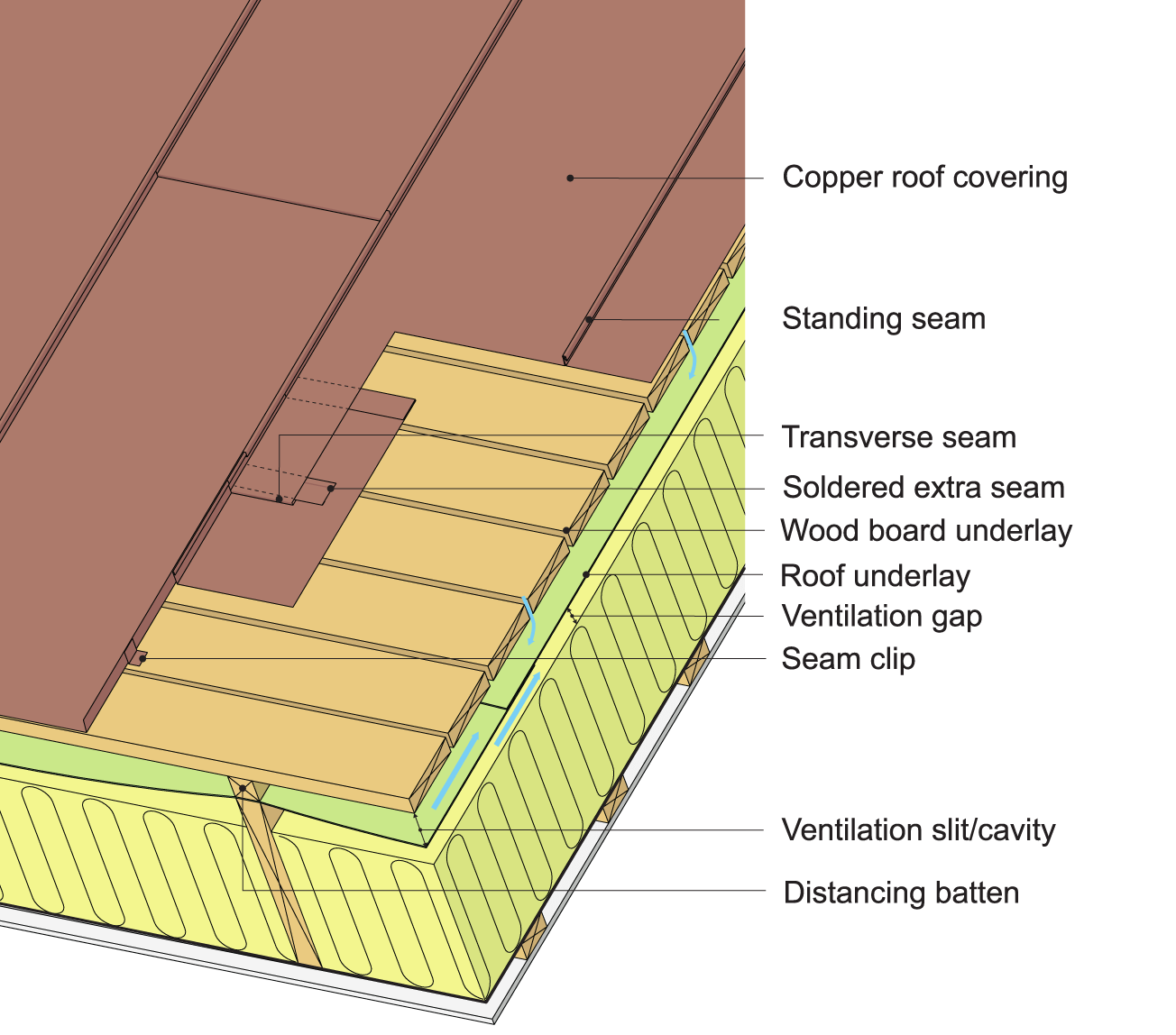

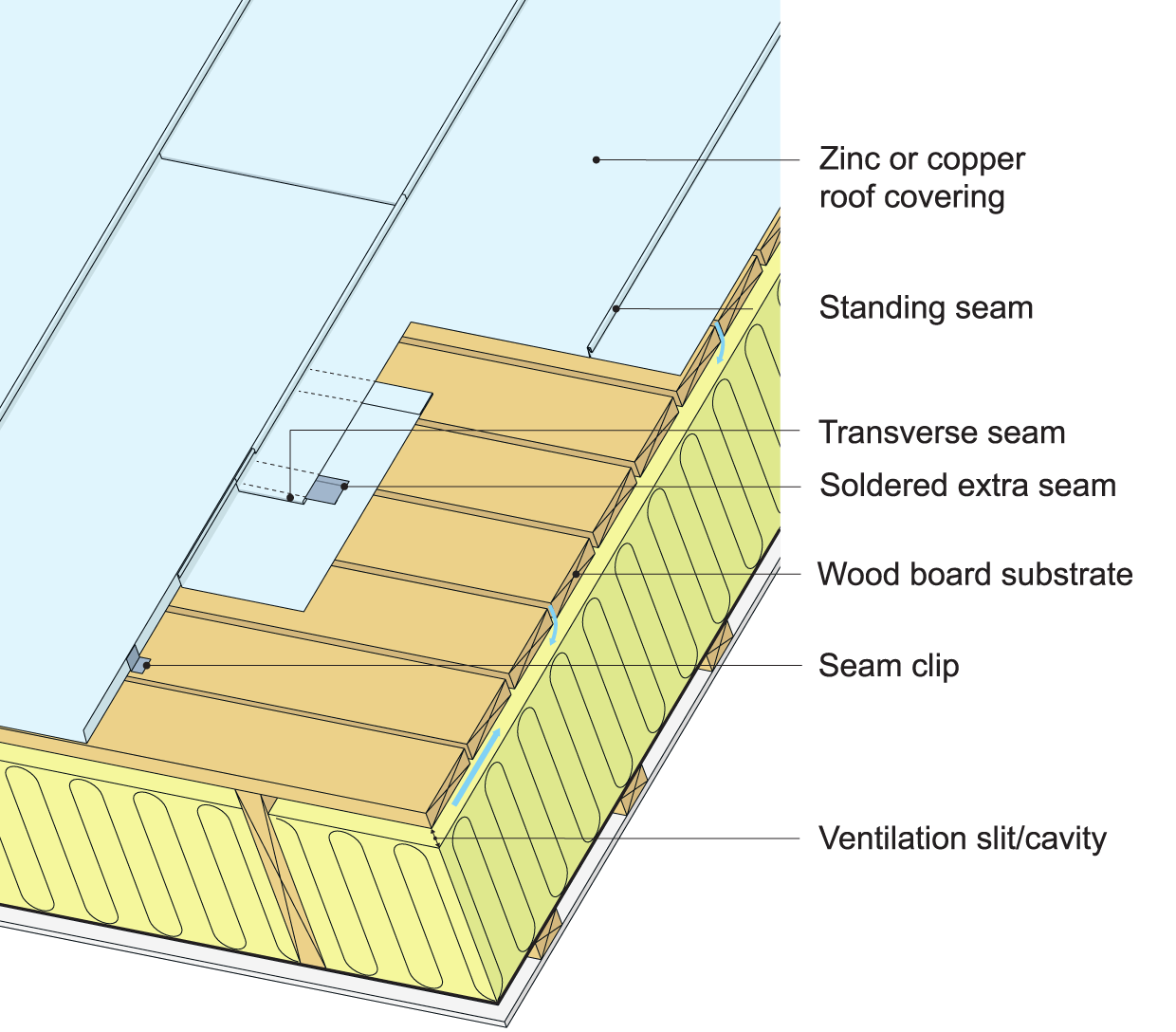

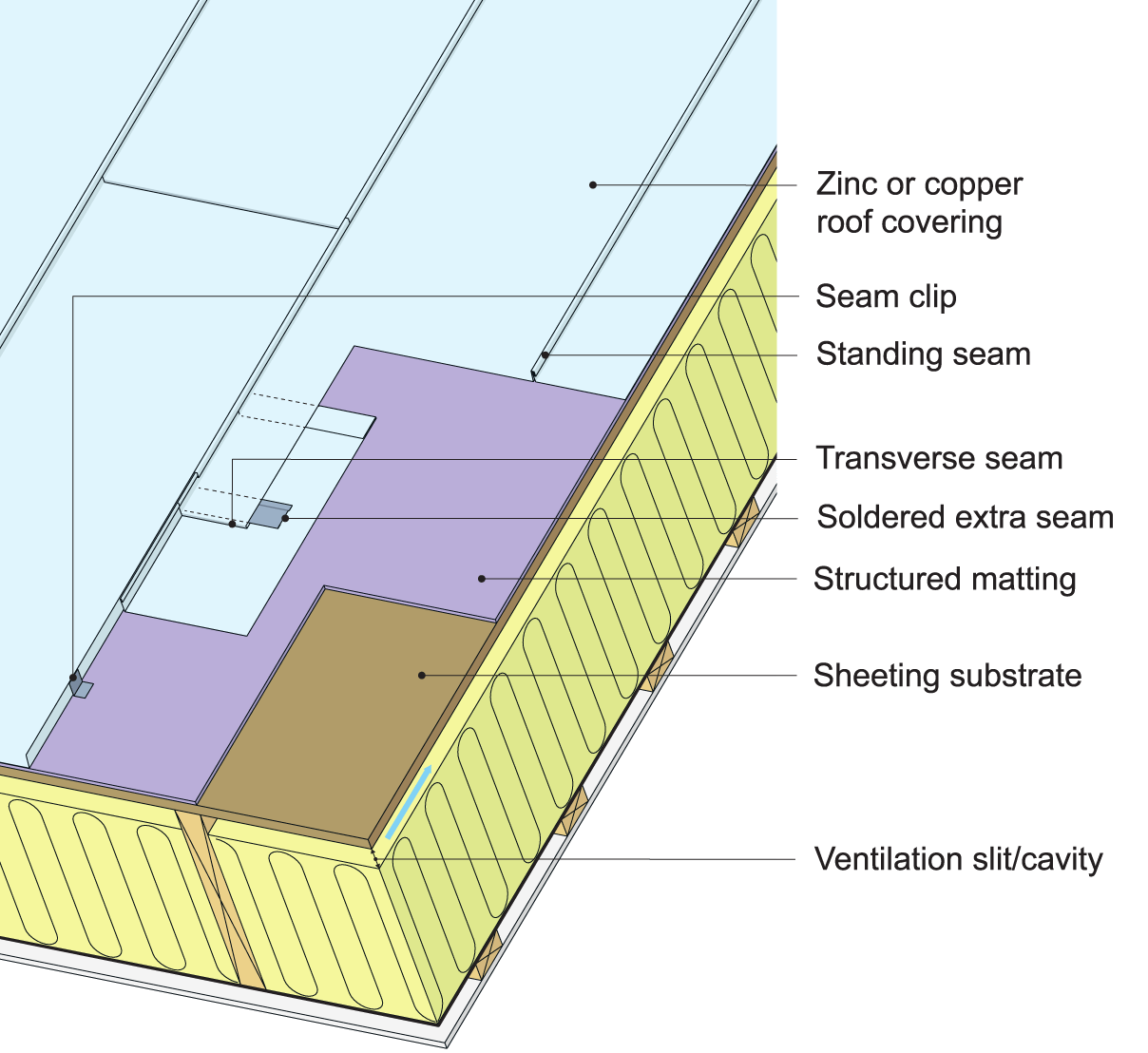

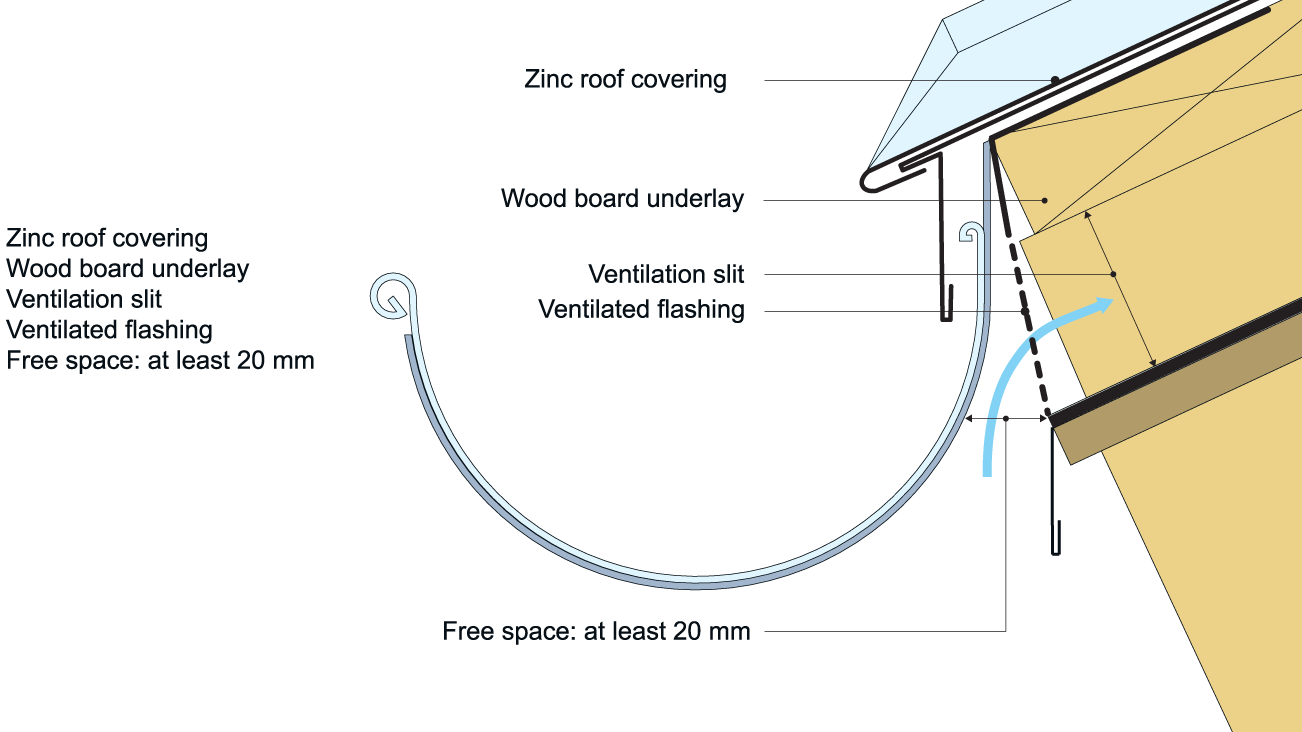

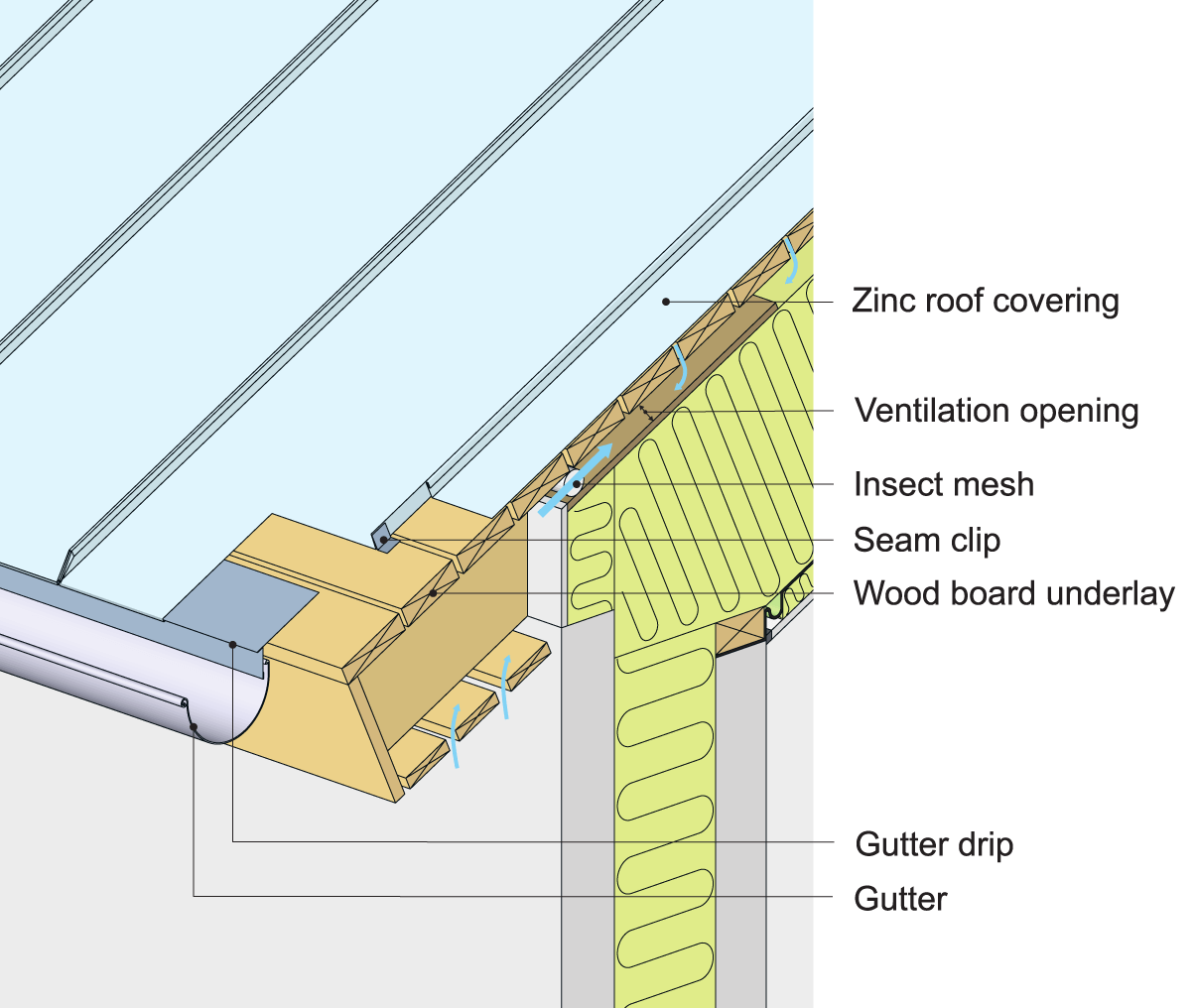

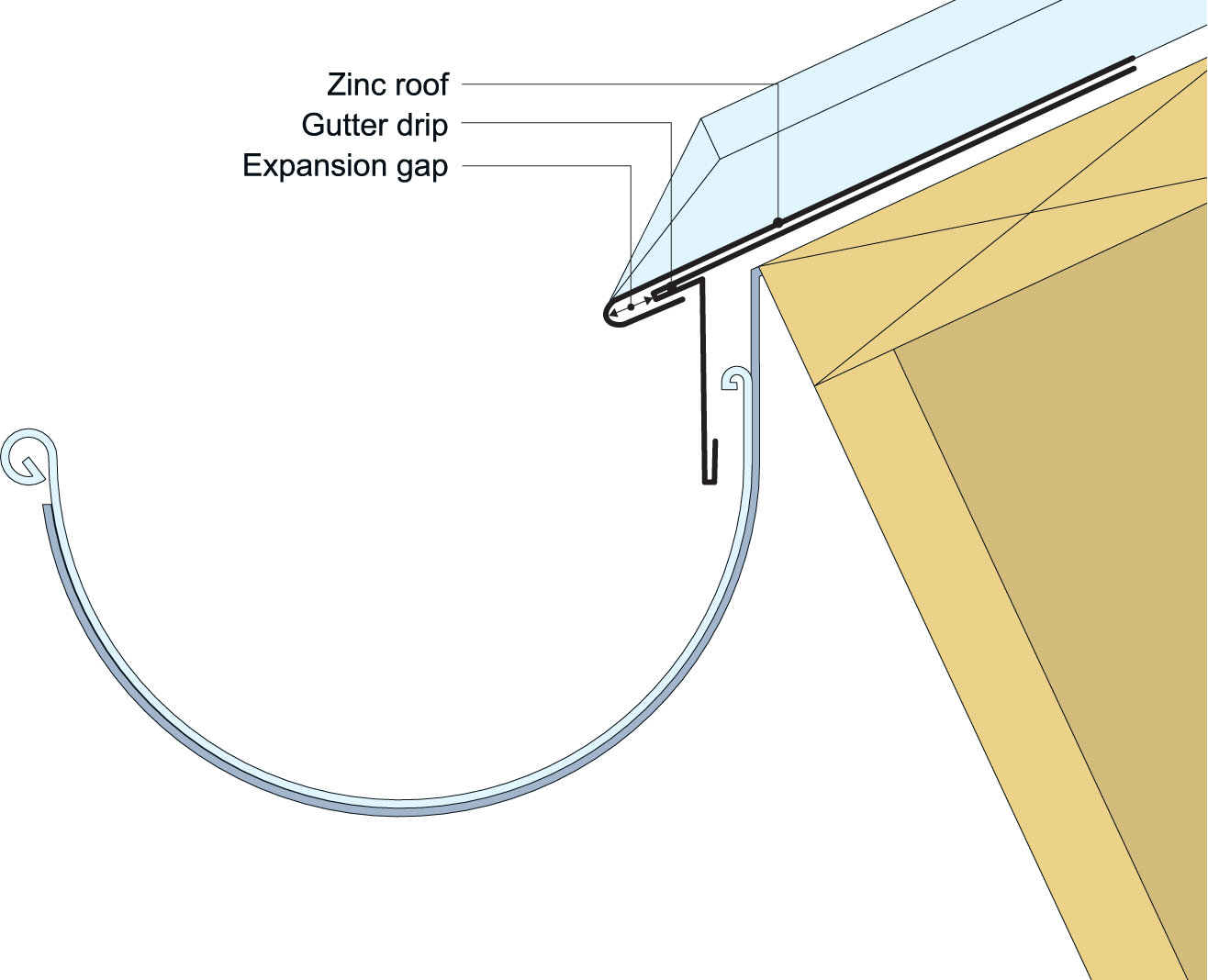

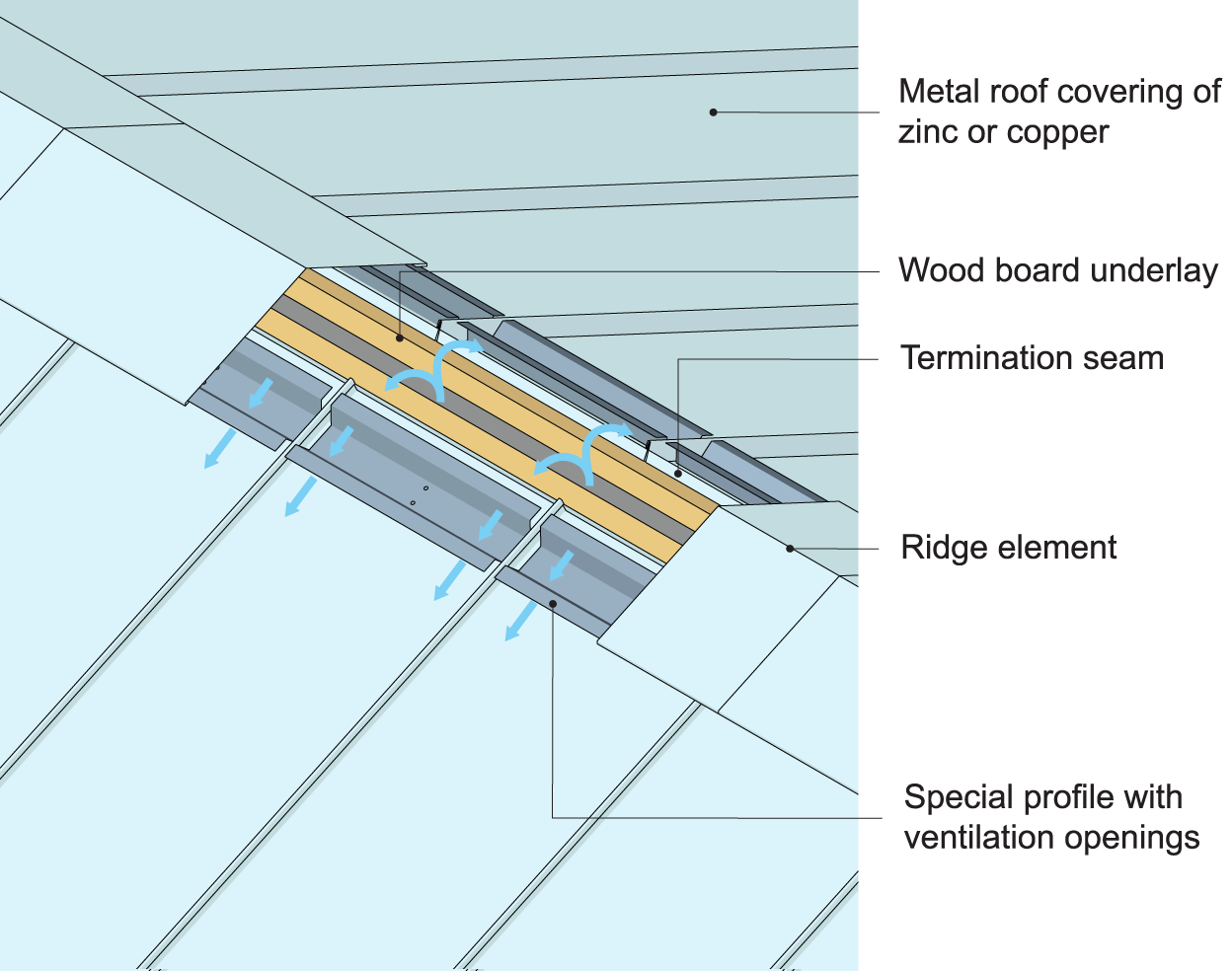

Zinc and copper must be installed on a plane and vented decking. A pH-neutral underlayment should be used.